To Download the related file click on the download button

Peer Gynt

– a dramatic poem

by Henrik Ibsen

Retold by Ian Harkness (Act One, Scenes One and Two).

Act One, Scene Three, is translated by John Northam. The rest of the remaining acts are translated by the Archers.

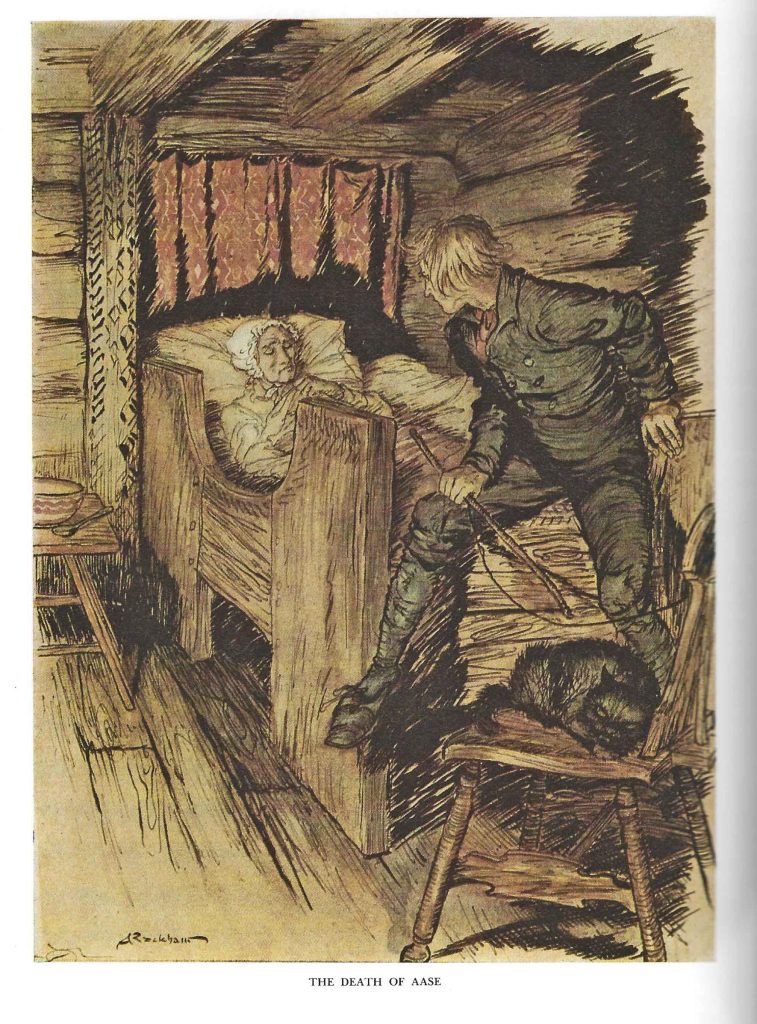

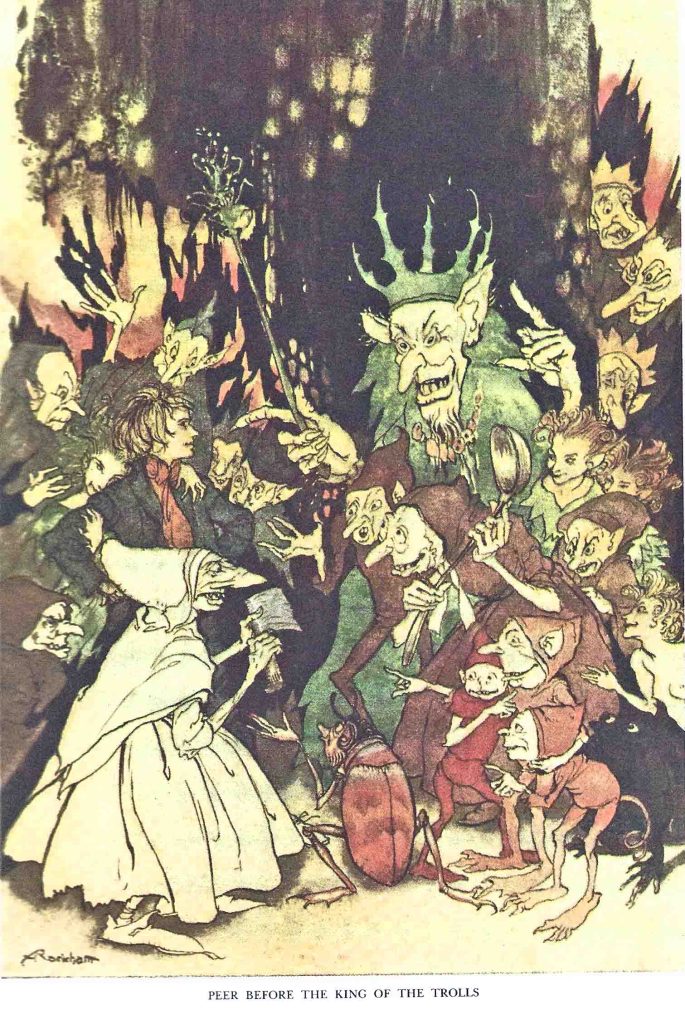

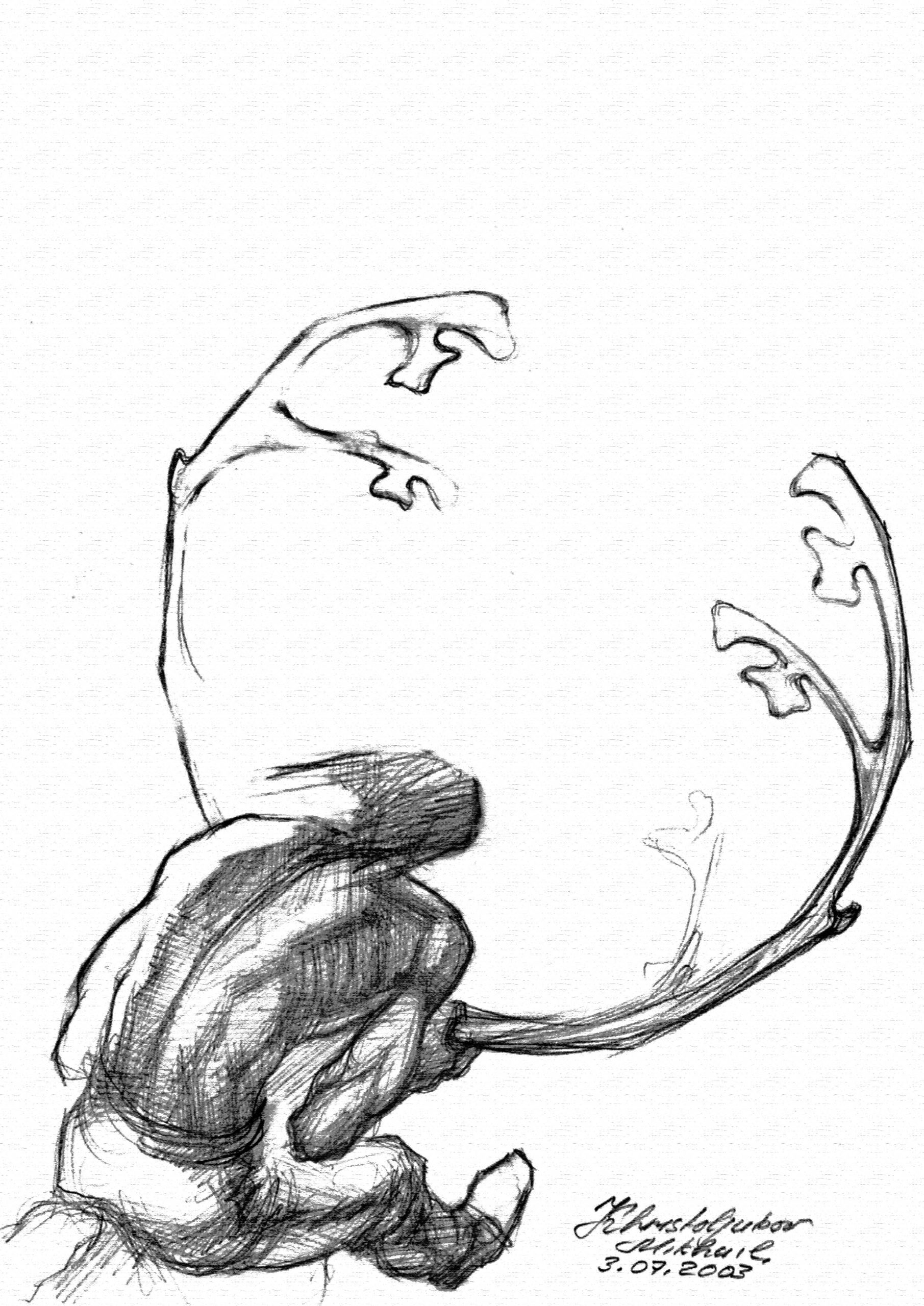

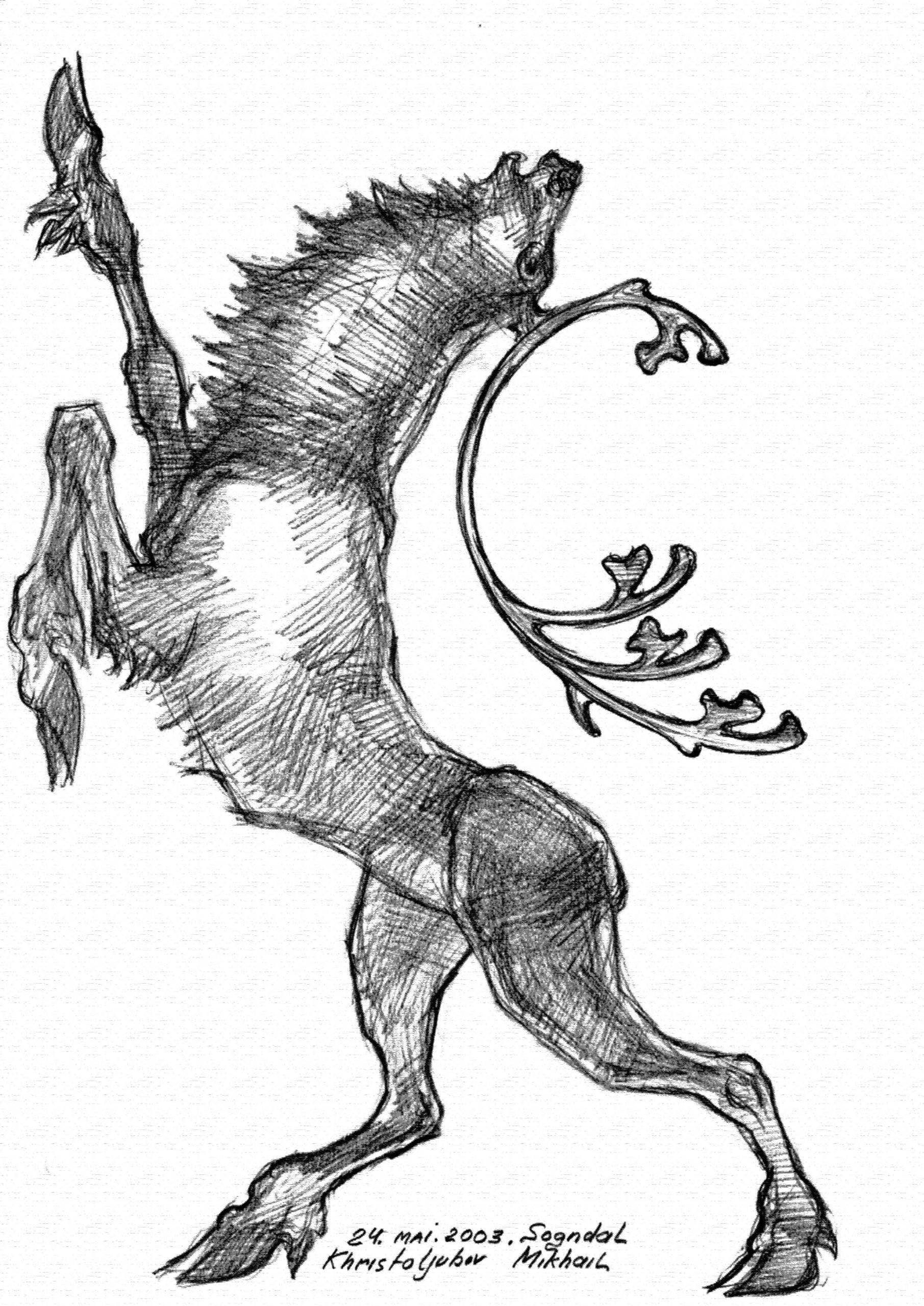

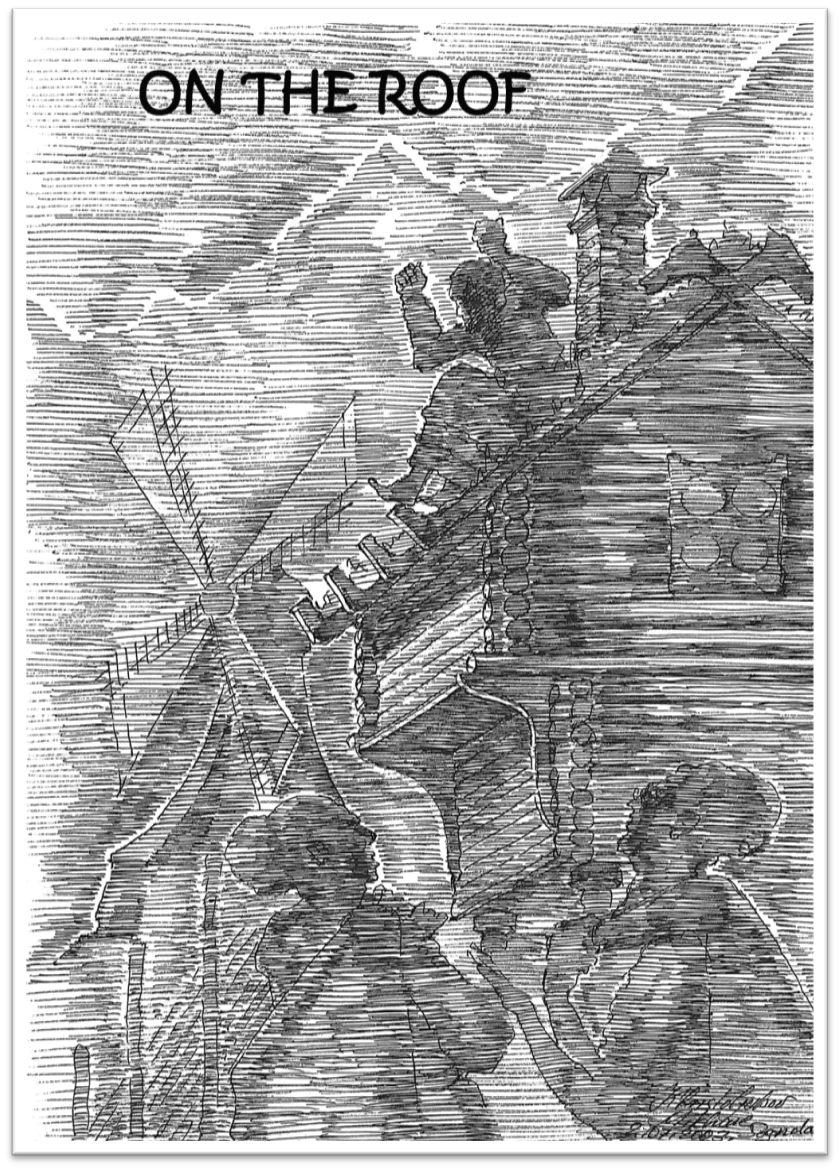

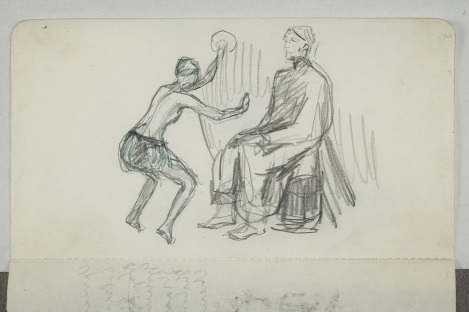

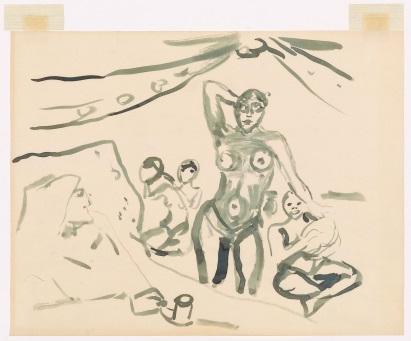

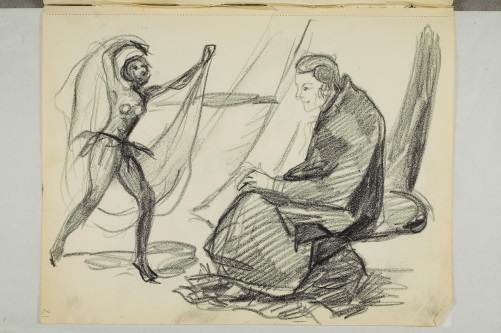

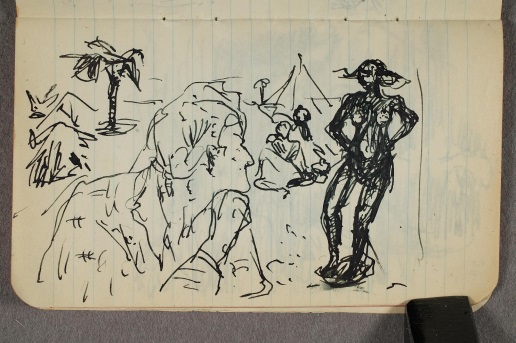

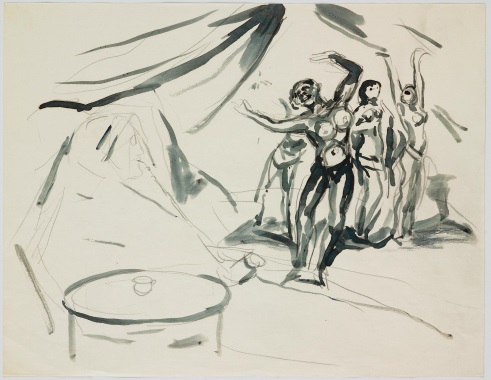

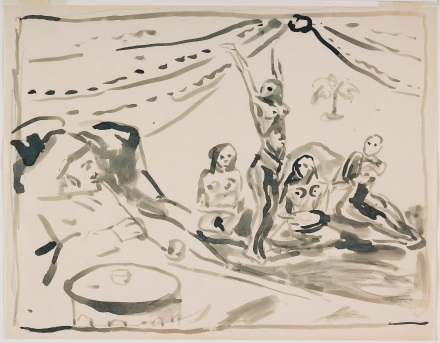

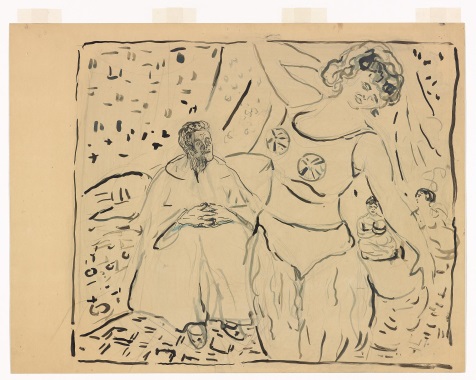

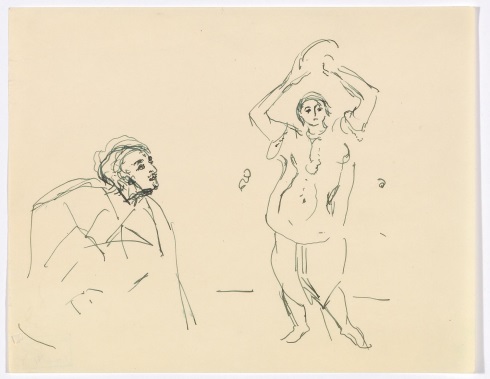

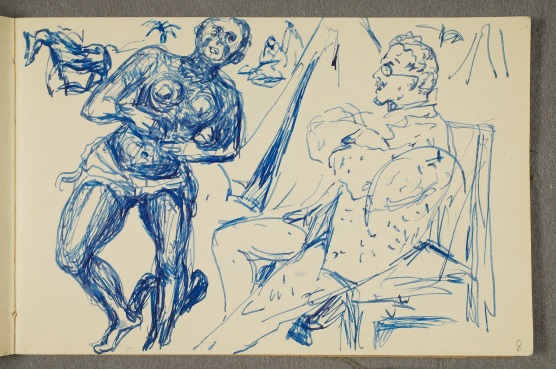

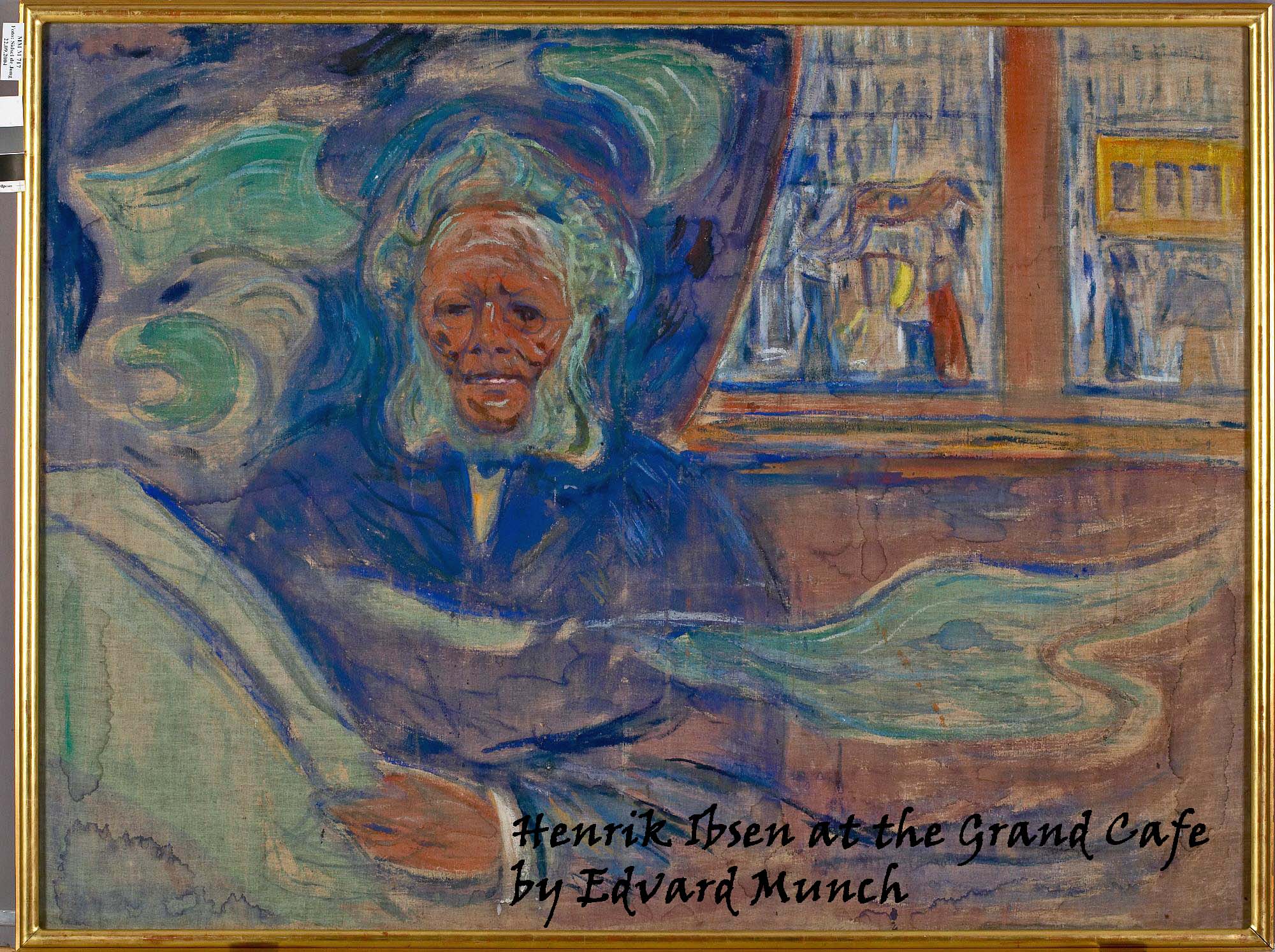

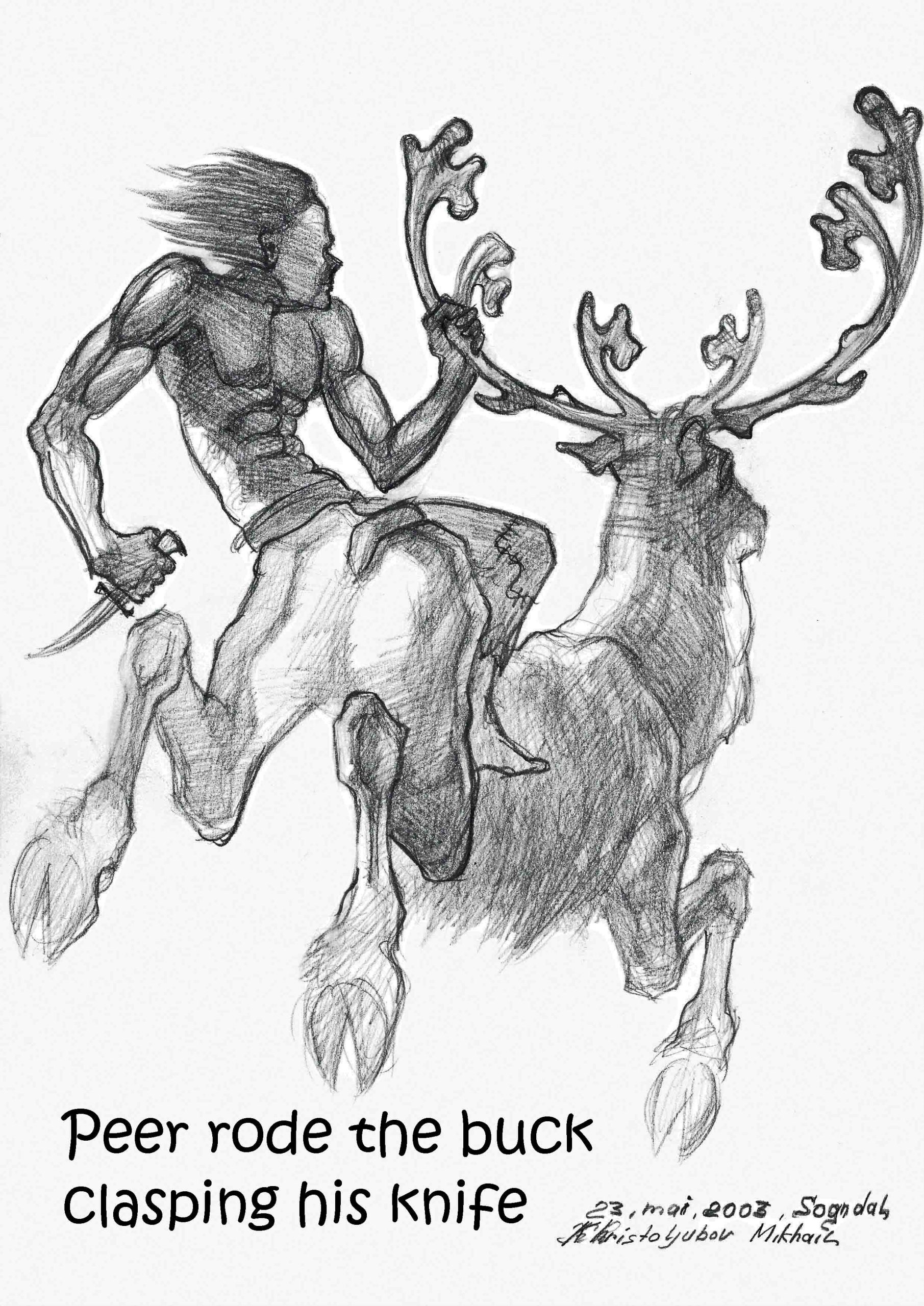

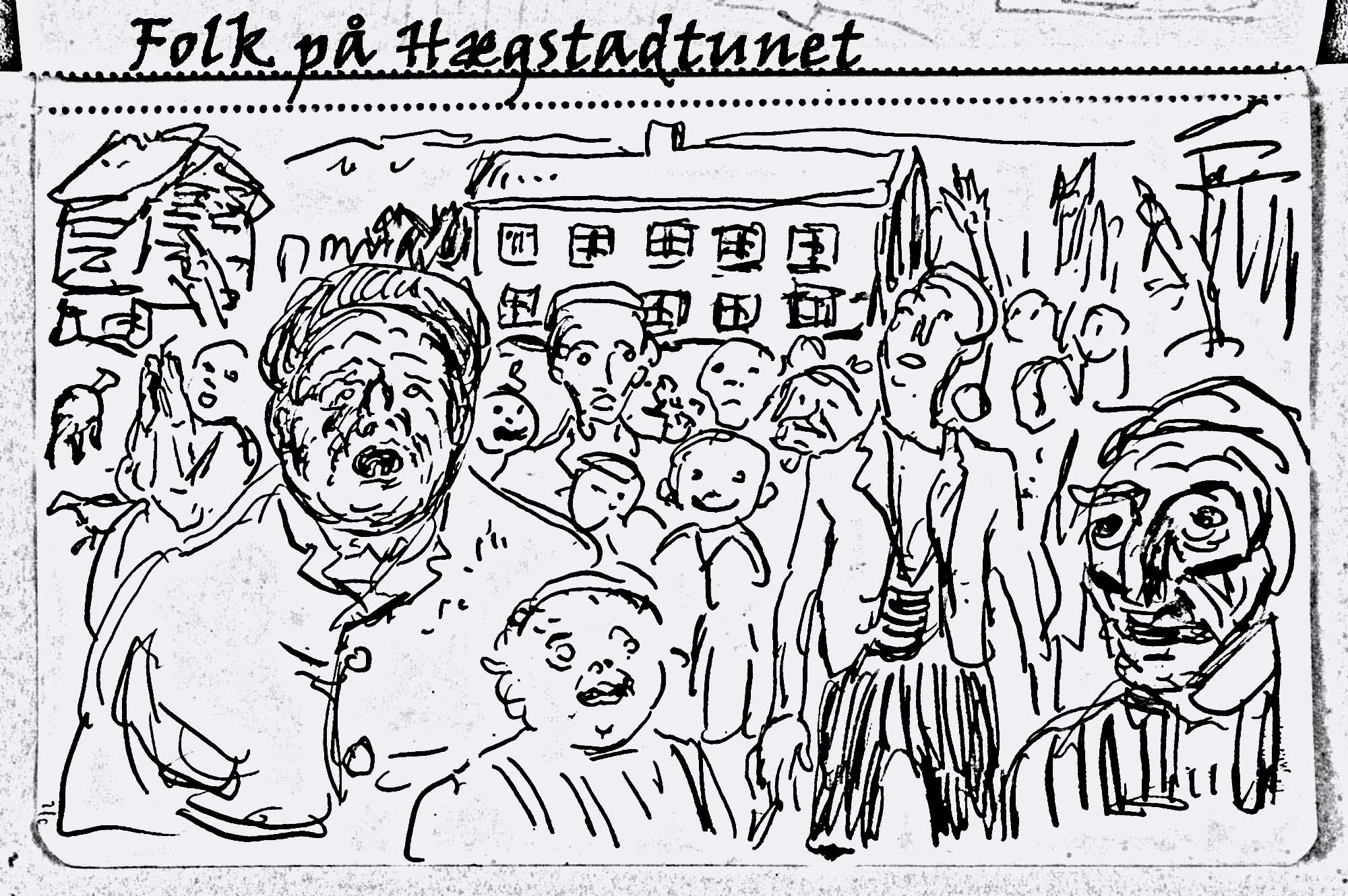

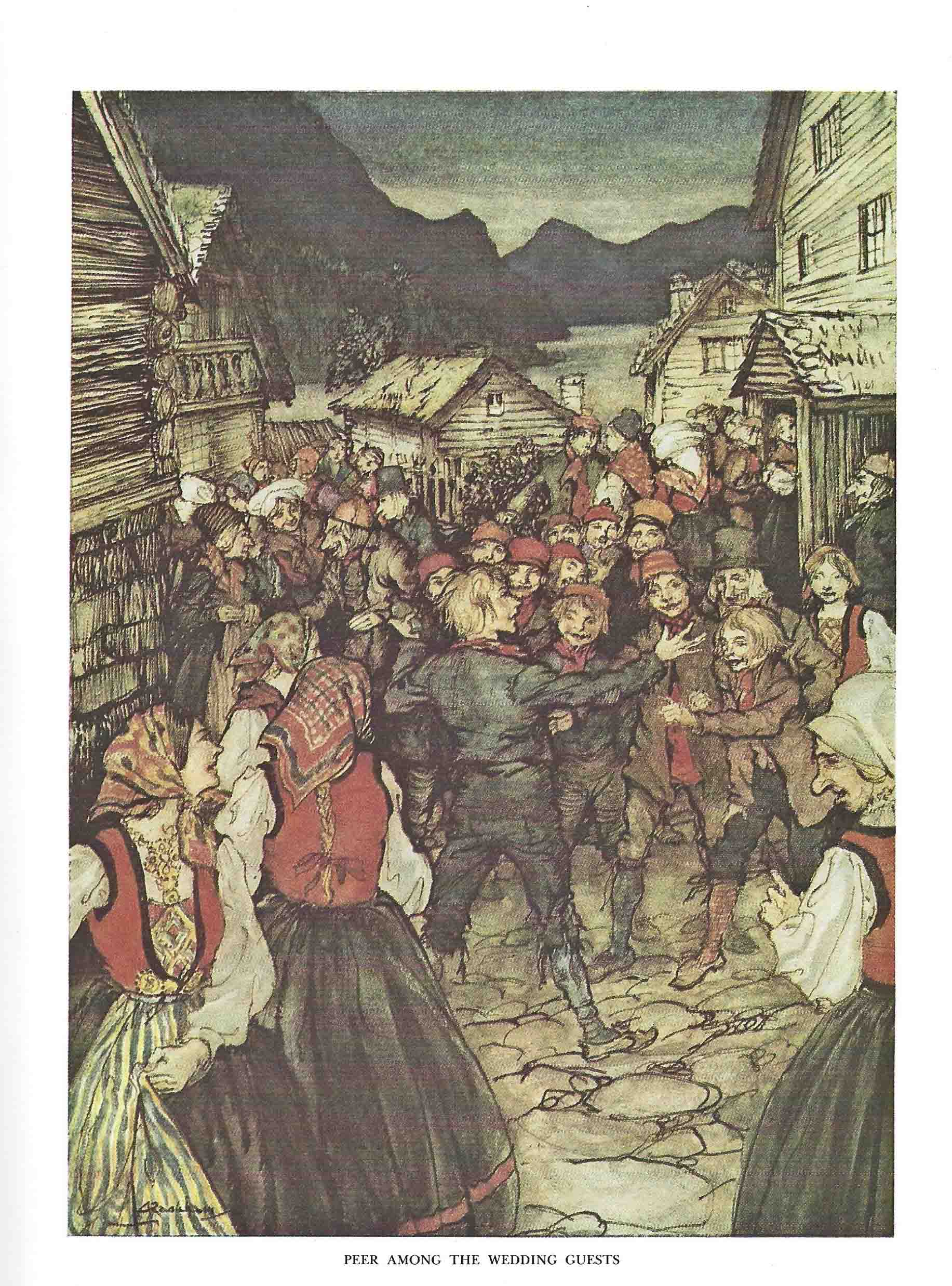

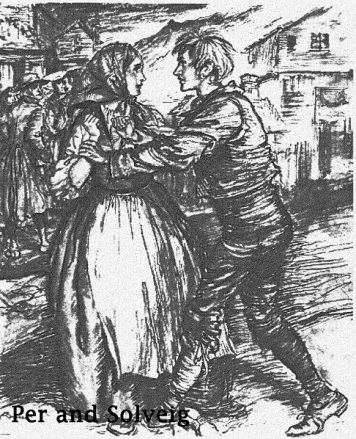

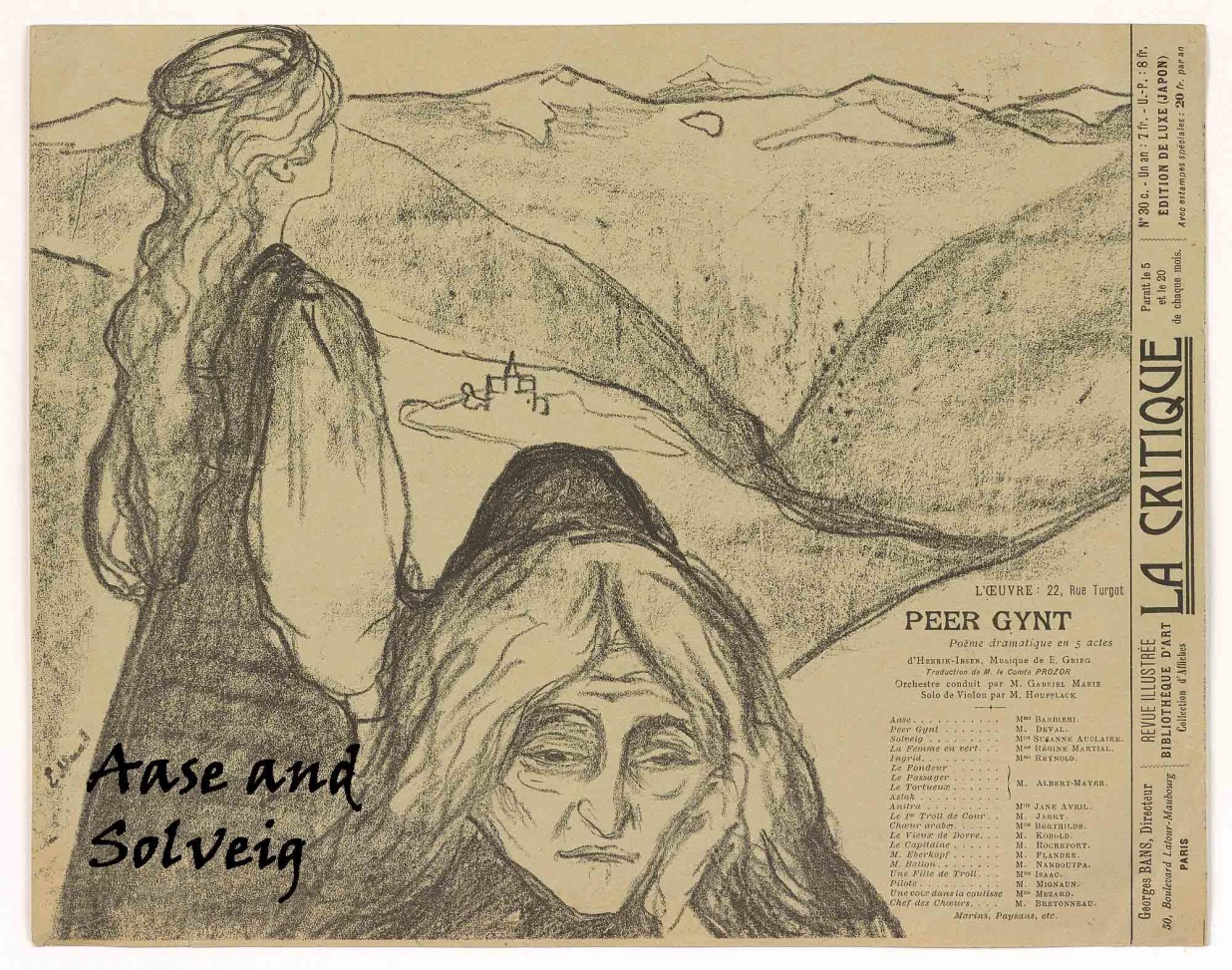

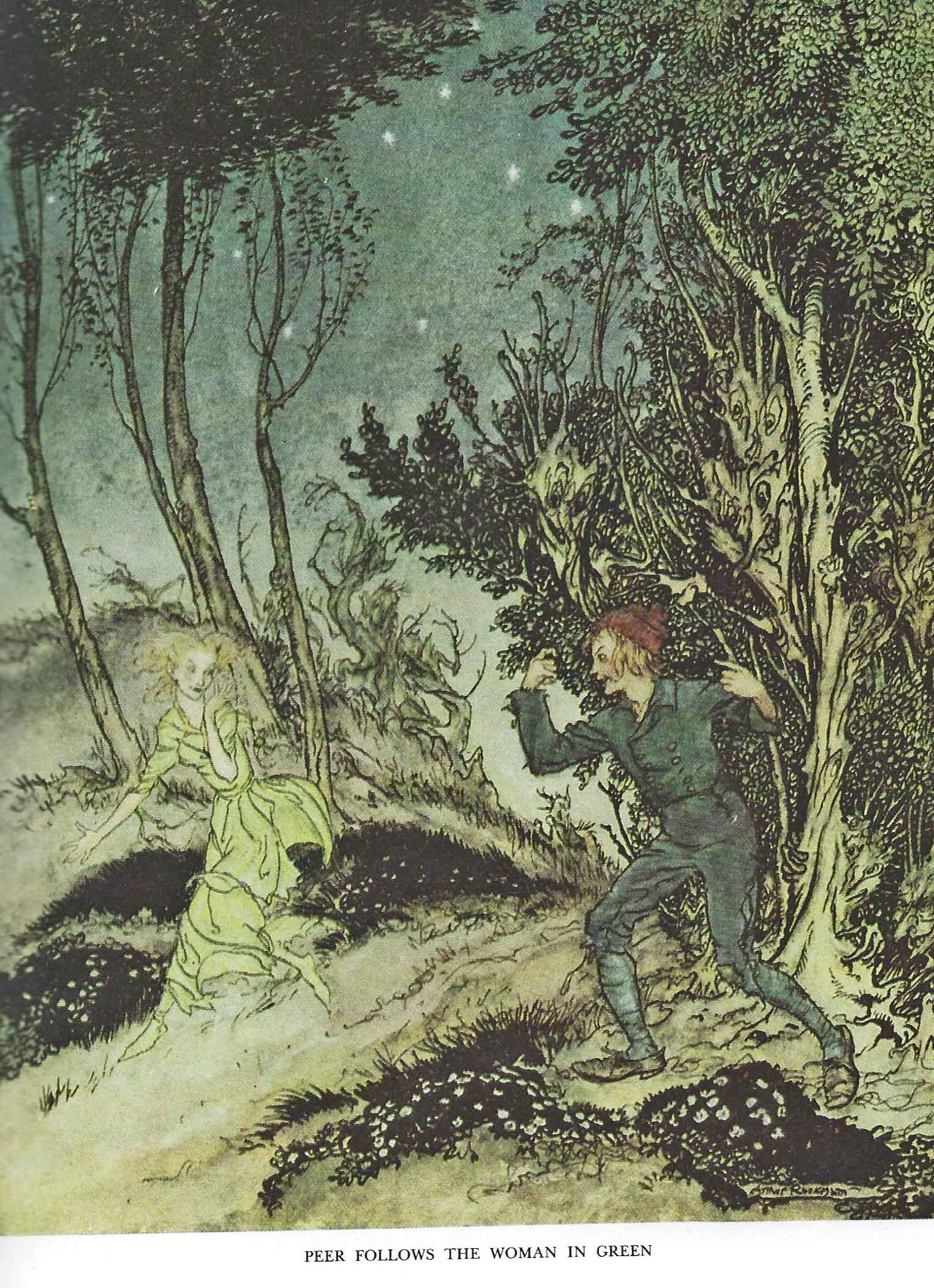

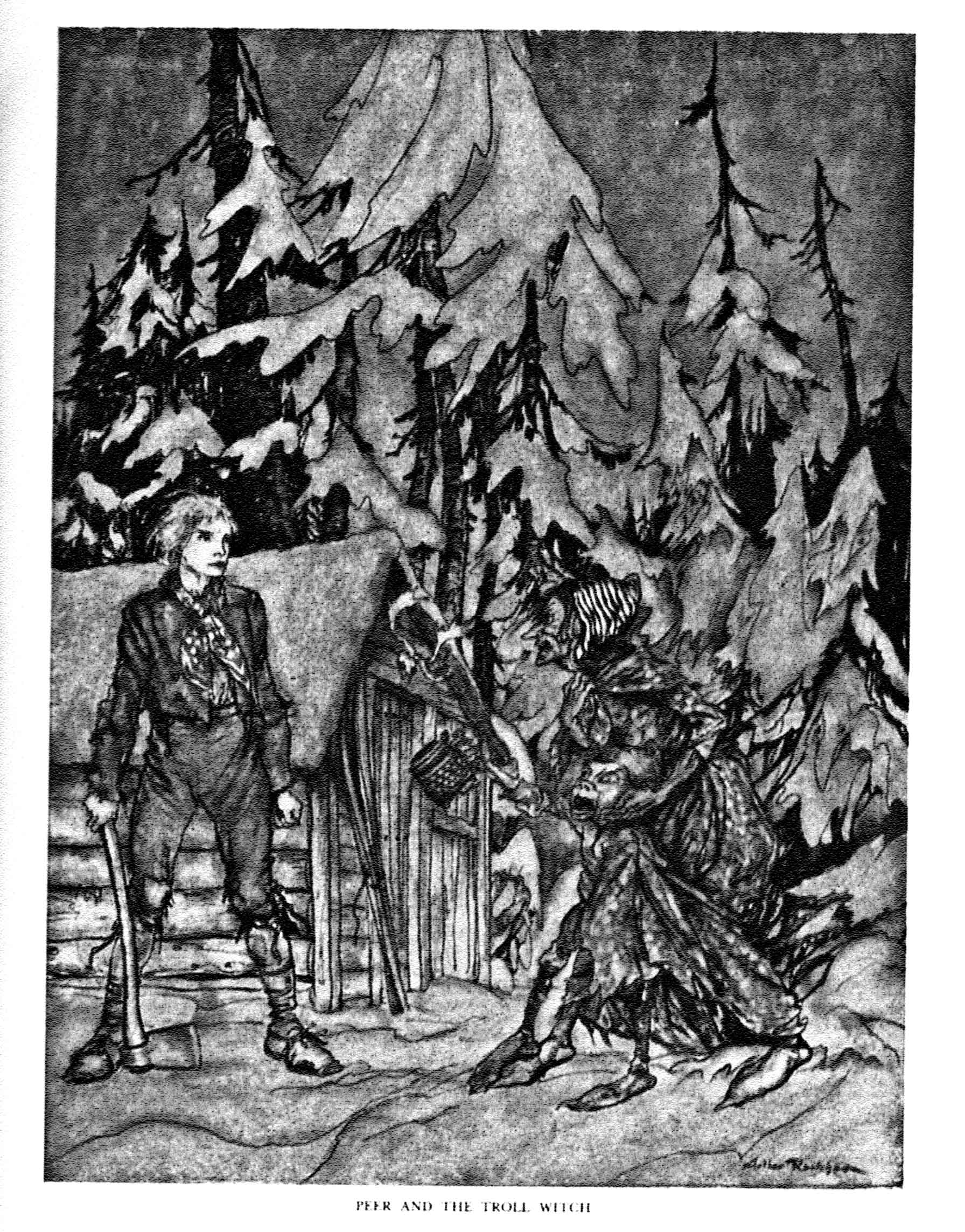

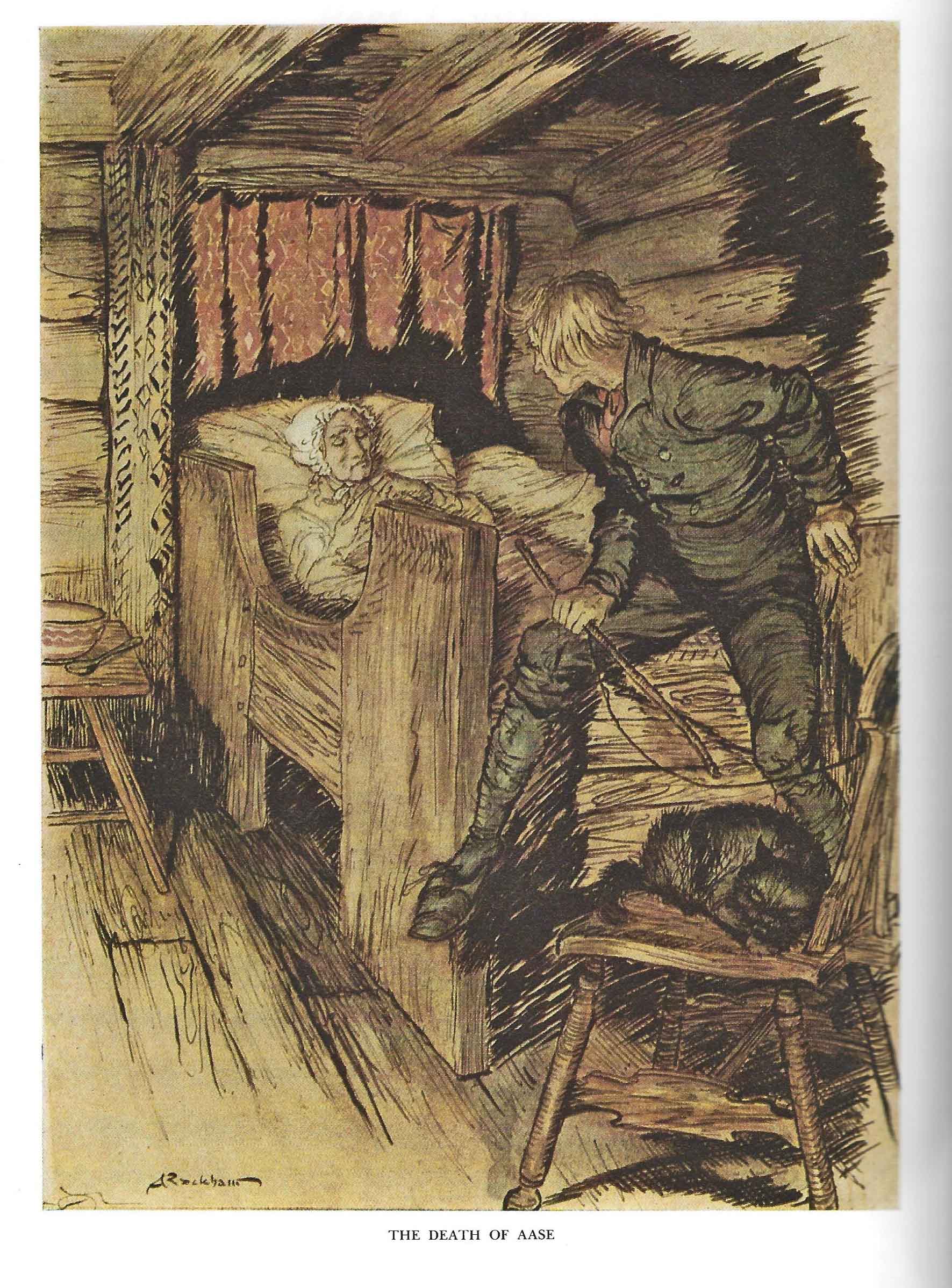

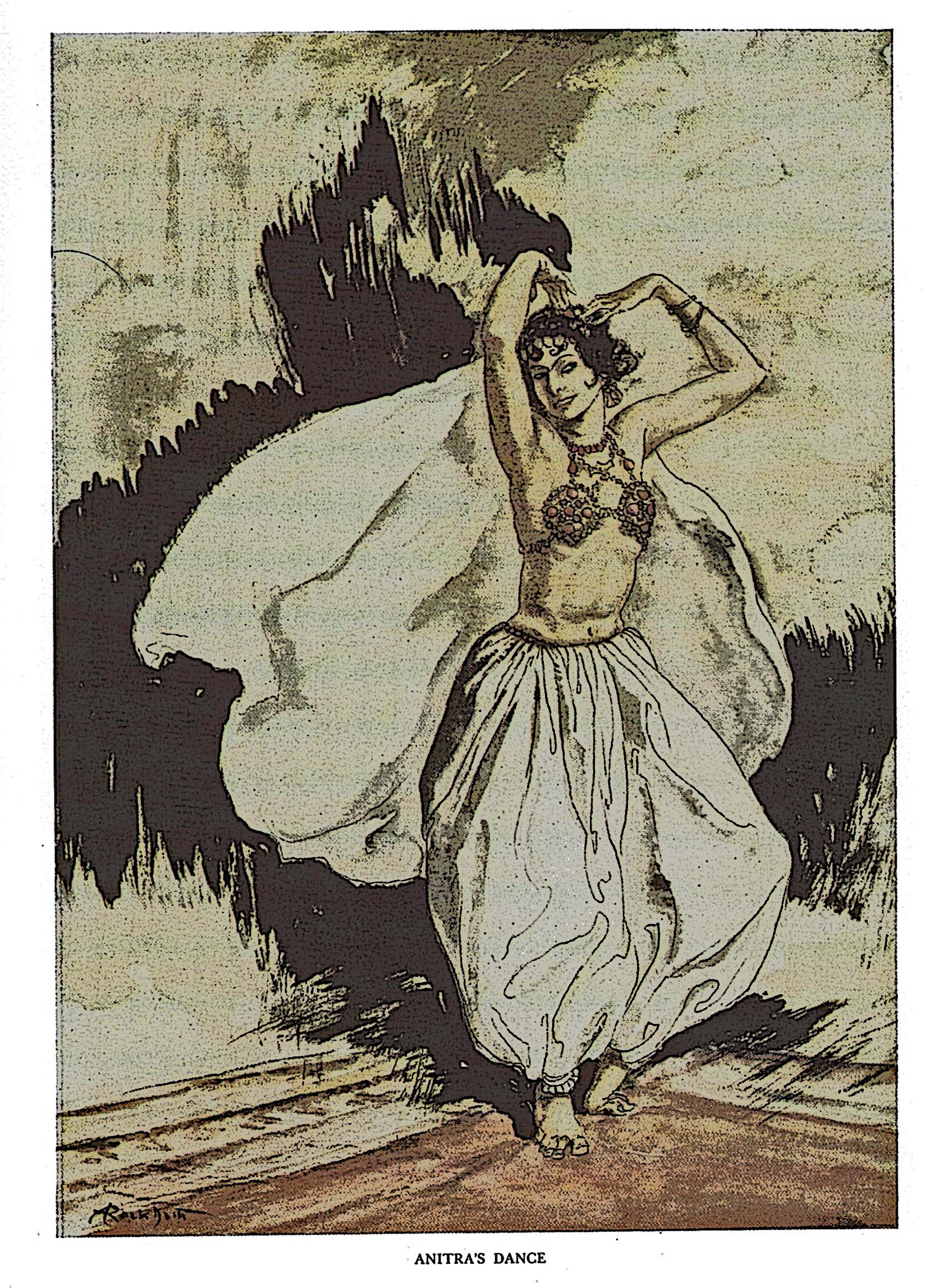

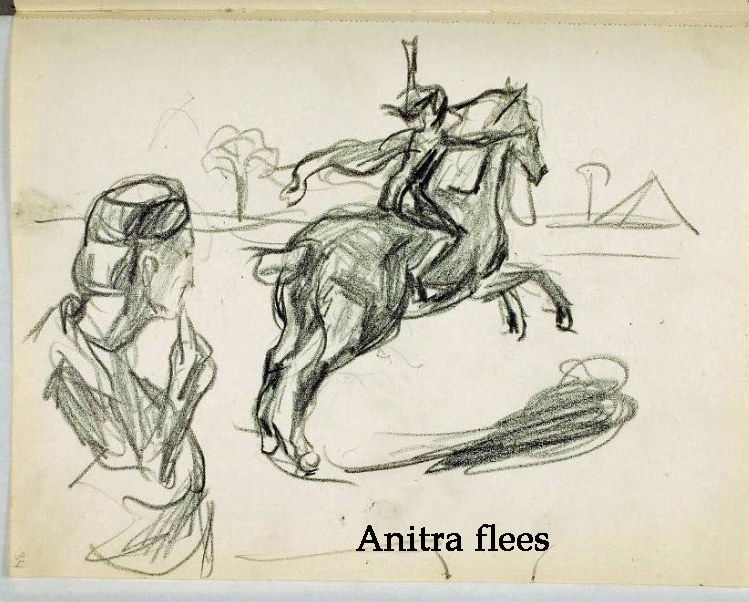

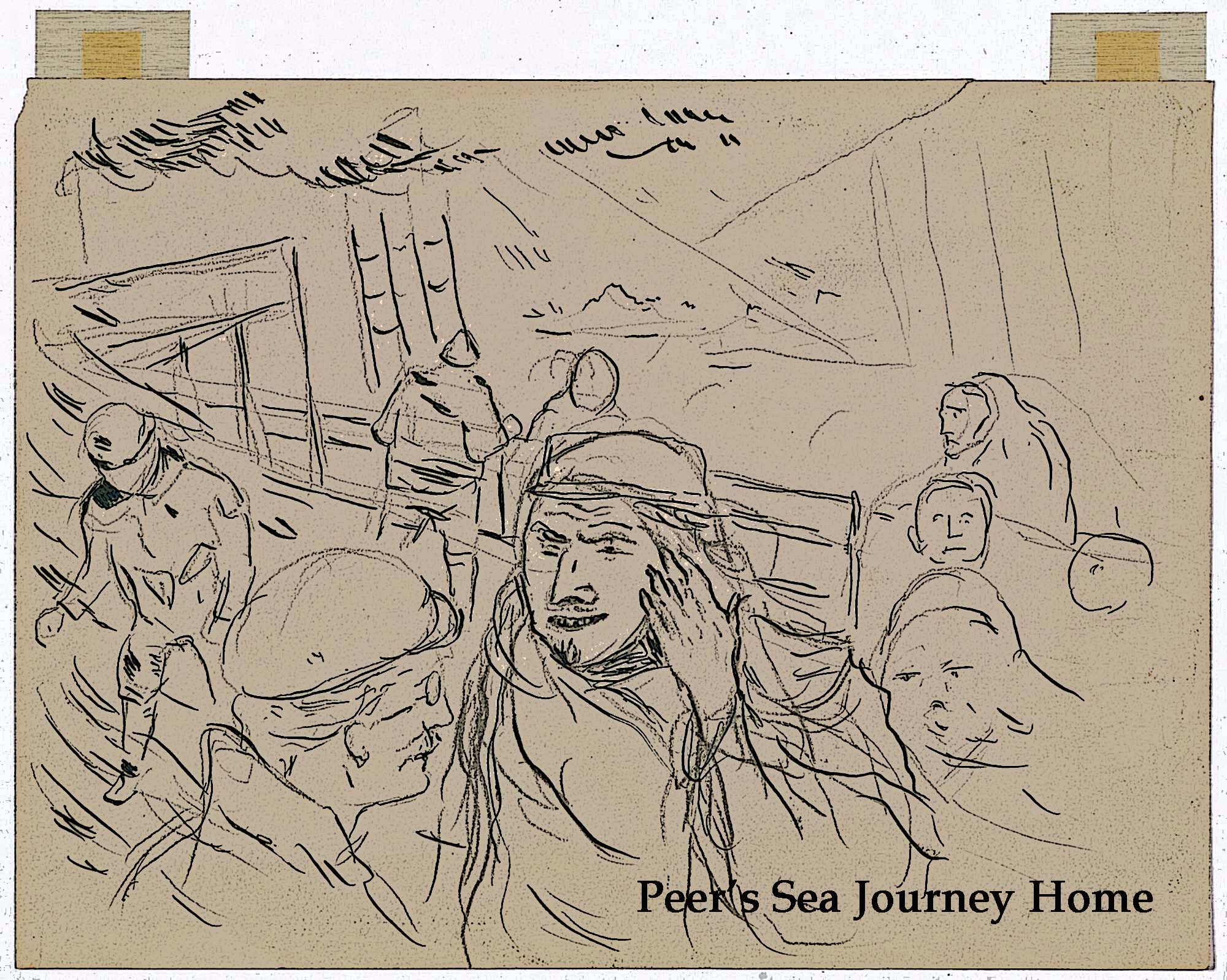

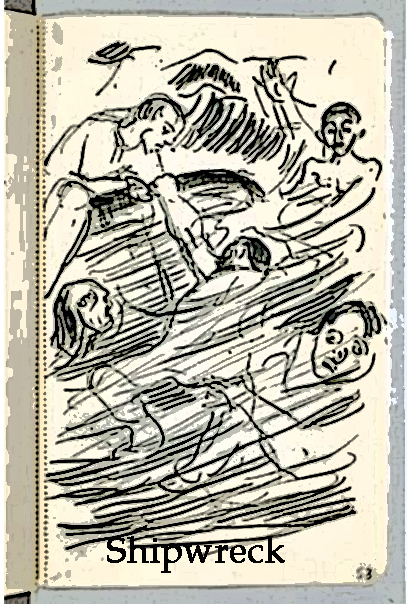

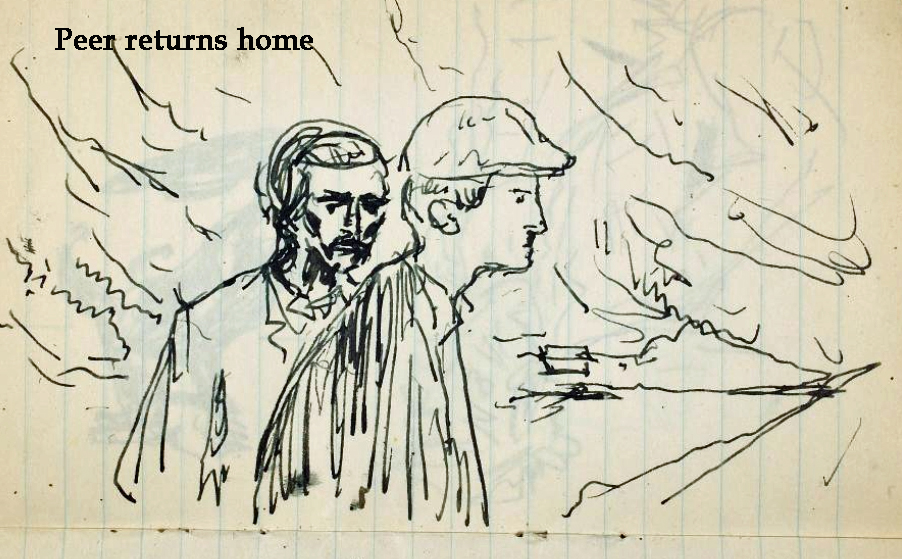

The play is illustrated by Mikhail Khristoljobov, Edvard Munch and Arthur Rackham.

Eos Publishers 2022

Contents

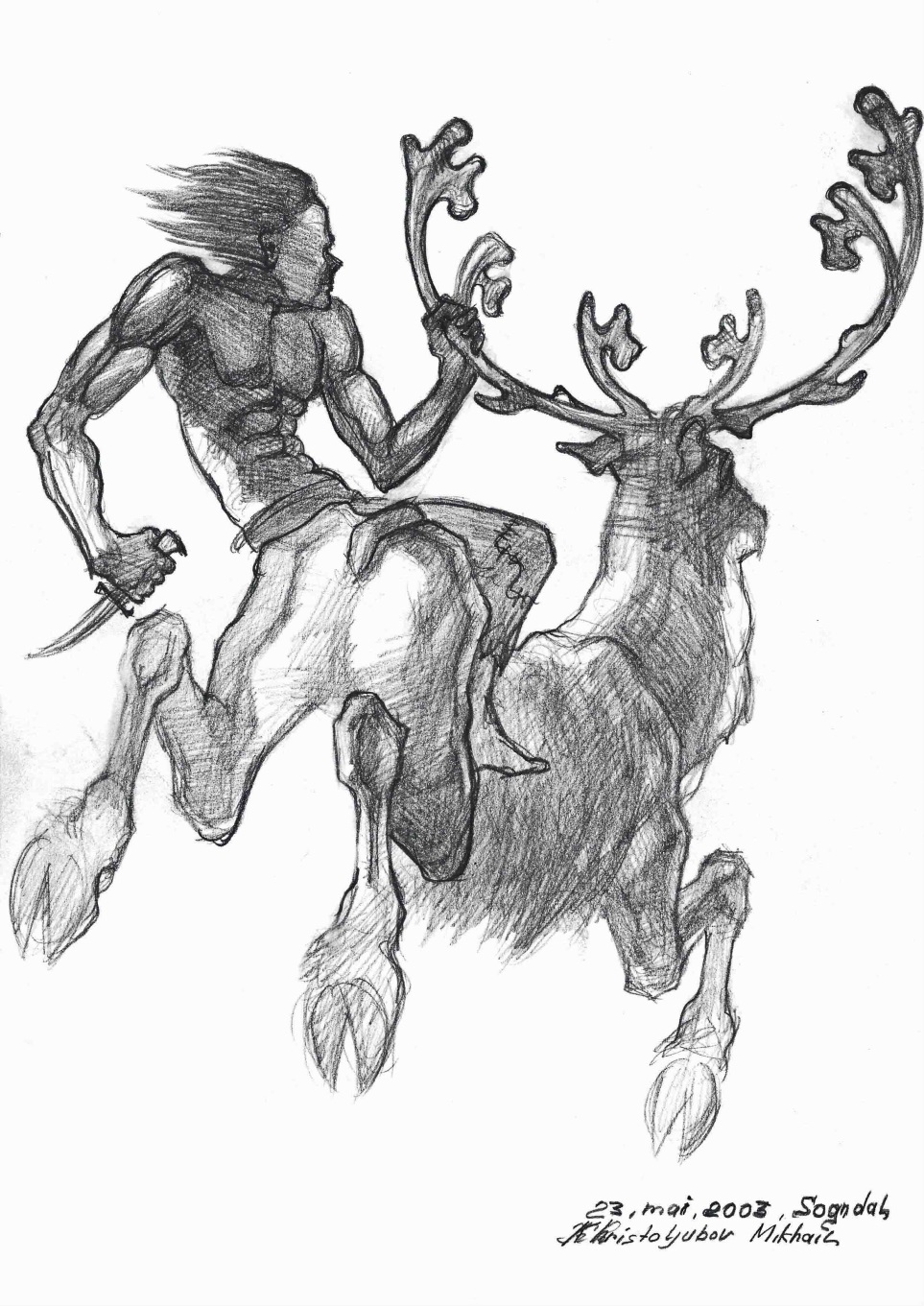

The artist Mikhail Khristoljubov 8

Mikhail describes his own situation 9

Mikhail Khristolyubov, Vasiljevich, born 9 September 1959 9

Link to Northam’s translation 11

Northam, John. Peer Gynt – A Dramatic Poem 11

Brief and cursory analysis of the translations 12

Peter Watts discusses the problems of translating “Peer Gynt” 14

What is a good translation? 15

An audio version of the play in English 16

Brief critical evaluation of the play 18

Some of my brief observations 20

Erotic elements in Peer Gynt 23

Folk culture, Peer Gynt and ‘the Fool’ 23

‘Politically correct’ Henrik? 23

Erotic elements in Peer Gynt 24

Fornicating with trolls with three heads – comical elements 26

Peer Gynt composed by Edvard Grieg 27

Norwegian text of the play 316

Rough English translation of “Gudbrand Glesne” 319

Introduction

Translator’s note:

I have translated the First Act and first two scenes. I have also translated the first two acts twenty years or more ago (around 2000). Unfortunately, in this digital age electronic files are often lost for various reasons. At that time, I used to visit the Centre for Ibsen Studies, which was located in the central-west part of Oslo. I remember at the time that I had the feeling of being a ‘lone researcher’. The facilities were excellent, and the study rooms ample, with few other researchers, and librarians to help you. However, I remember it wasn’t so simple, as I discovered at least 16 translations of Ibsen’s Peer Gynt into English! I had the mad idea that I would cross-check all the translations for every single line in the dramatic poem! I’m including a lot of exclamation points here as a kind of ironic comment on Ibsen’s play! I haven’t counted the number of exclamation points in Act 1, Scene 1, but it is surely 100 or more! Obviously, Henrik Ibsen never watched a Seinfeld episode, as he died some 70 years or more before the TV sitcom was aired. However, had he seen the episode “The Exclamation Point” (1993)[1], he had perhaps been a little more thrifty with his exclamation points! The whole point of an exclamation point is to make a contrast – thus, if every other line has an exclamation point, then the effect is lost! This is perhaps one of the basic principles of rhetoric technique!

But to return to the translation process, I am perhaps fortunate that I’m a born naïve optimist. So, one day I thought – let’s translate Ibsen! This was not part of any college project, just something done under my own initiative with no particular goal in mind. Of course, this is more or less unheard of in the modern world – doing something with no profit-motive in mind. But, back to the point – I soon discovered that Peer Gynt was much more complex than at first sight. I had not initially noticed that the play was not a regular ‘play’ as such, but a play written as a poem.

I won’t go into all the details of why it is difficult to translate a ‘poem’ from Norwegian into English. Iambic meters are common throughout English poetry: “When a line of verse is composed of two-syllable units that flow from unaccented beat to an accented beat, the rhythmic pattern is said to be an iambic meter.”[2] Peer Gynt uses a variety of metres in its rhymed verse, some of which are little used in English poetry. Without going into an analysis of the metre in Peer Gynt, it goes without saying that the metre and rhythm differs from English poetry, just as the metre and rhythm of the English language differs from that of the Norwegian language, or any other language for that matter.

Translation ‘problems’

I remember that I gave up on the idea of ‘rhyming’ the translation, but decided to try and resemble the metre of the original. As mentioned, my original translation is ‘lost’ – or rather I found the first few pages on my computer up to the point:

ÅSE

O, din slagsbror! Du vil lægge

mig i graven med din færd! (Act one, scene one, line 234).

As mentioned, the rest of the translation (of the first two acts) is lost, so I have decided to at least ‘re-translate’ the rest of Act One, Scene One beyond line 234, as well as Act One, Scene Two. Originally, I attempted to replicate Ibsen’s metre (up to line 234); however, for the rest of Act One, Scenes One and Two, beyond line 234 in Scene One, I have only focused on ‘content’, and not on rhyme and metre. For the rest of the play beyond Act One, Scenes One and Two, I have used the translations of John Northam, and Charles and William Archer.

My aim is not so much to ‘showcase’ my own translation, but to give me the opportunity to post online the excellent drawings of the gifted Baltic artist Mikhail Khristoljubov who has provided illustrations for Act One. To complement his drawings, and also to illustrate the play beyond Act One, I have included drawings by Edvard Munch and Arthur Rackham.

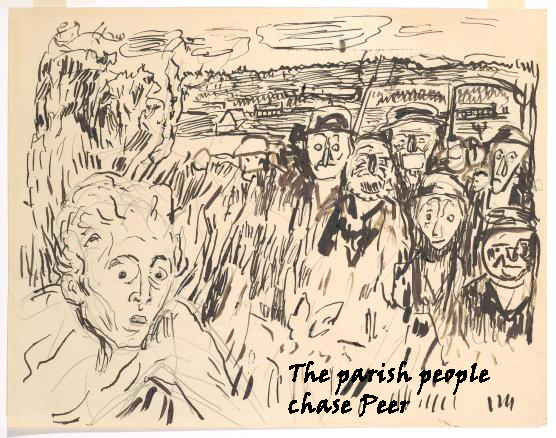

The artist Mikhail Khristoljubov

I met Mikhail while living in the west of Norway around the turn of the century, when I was working as a professor at Sogn and Fjordane University College. He was living a meagre existence on a universal basic income in a refugee camp in the region. He spent most of the day weaving magic with just scraps of paper, pencils, and cheap ball-point pens. I only regret that we lost contact, and I wasn’t able to see more of his magnificent creations. Nevertheless, he has illustrated two of my books (three including “Peer Gynt”). These are posted online (see footnote).[3] I can’t remember exactly how I met him, but he was fluent in Russian, so it seems likely that we met through some kind of contact between him and my ex-wife Natasha, who is Russian. In fact, my poor ex-wife helped me on this project by being our interpreter, as he spoke little English. All the illustrations to the various books were orchestrated by me in detail (which she had to explain to him, and supply written instructions in Russian; I also provided ‘guide’ drawings that I had found in various books and on the Internet).

In other words, Mikhail was existing on the basic universal income doled out by the Norwegian government. The Norwegian government didn’t want to offer a too large an income, so as not to attract too many refugees (‘foreigners’) to the country. I should perhaps thank the Norwegian government, because the minimum ‘universal basic income’ meant that refugees were often looking to supplement this income. Of course, if I were to hire second-rate Norwegian artists at five times the cost this would be unsustainable! I can’t remember the exact fees I paid Mikhail, but it wasn’t a large amount. I might have a bad conscience if I was exploiting third-world labour – but my conscience is clear as my projects were non-profit making – unlike profit-seeking American companies that have exploited cheap Asian labour over the last 40 years. In fact, the so-called ‘liberal-democratic’ company Apple have, in 2022, managed to create a ‘capitalist-heaven’ of forced labour, that is, workers are locked-in factories in China.[4] This seems to resemble the Nazis use of forced labour in VW factories during World War II.[5] The recent example we have of this exploitation of labour is the billionaire Elon Musk – who up until recently was the richest man in the world. He has recently acquired Twitter and quickly decided to make himself richer by sacking a large part of the workforce.[6]

Mikhail describes his own situation

I had asked Natasha to ask Mikhail how he had ended up in Norway as a refugee. He provided the following account, which Natasha translated into English:

Mikhail Khristolyubov, Vasiljevich, born on 9 September 1959

At an early age, he lost his parents, and was raised in children’s homes. He has many gifts and talents, such as artist, designer, inventor, musician, poet, writer and critic. He studied at the Latvian Art Academy. From a young age, he was critical of the Communist regime, and thus came under the surveillance of the KGB. He was a strong critic of the Communist order during Gorbachov’s rule. This resulted in him becoming a target of persecution. The government at the time made several attempts at reprisal. Consequently, he fled to Finland, where he lived illegally. At the moment (in 2003), he is living in Norway as a refugee.

Instructions for Mikhail

I had instructed Mikhail to make drawings to illustrate my translation of Ibsen’s play. Unfortunately, the practical demands of everyday life interrupted this project – so, we never got past Act One. However, artists always have their ‘unfinished works’, so I will use this opportunity (in 2022) to ‘complete’ this unfinished project by posting it online.

Entrepreneurial ‘heroes’

The inventor, author, artist, and so on are the central heroes in the capitalist world of the last 300 years. Of course, anybody with an iota of intelligence realises this is just silly. The capitalist ideology is heavily dependent on the idea of the creative individual. However, we can’t really enter into a lengthy discussion here, but even a simpleton is able to understand that ‘inventions’ are not the work of one man. Karl Benz may have ‘invented’ the internal combustion engine and the modern motorcar in 1885/1886. But, this is of course absurd! Steam-driven vehicles were invented some 200 years before![7] The ‘wheel’ was utilized some thousands of years before![8] In other words, Benz was developing ideas, and not a creator of a totally unique product. But as mentioned, the ideology of capitalism is heavily dependent on the idea of the ‘creative inventor’ / ‘author’ / ‘artist’ / ‘entrepreneur’, and so on; that is, the ‘individual’; this is bound up with democratic rights as opposed to the oppressive regimes of aristocratic hierarchies. In other words, James Watt did not ‘invent’ the steam engine, but he made various incremental improvements on earlier steam engines, such as Newcomen’s steam engine.[9] This long interlude is an attempt to explain that cultural products are often collaborative projects, and an attempt to explain why I’m ‘appropriating’ the translations of others. As mentioned above, I originally based my translation on 16 translations, and of course my own interpretation. At the moment, I have found some translations of Ibsen’s play in my archive:

Translators of “Peer Gynt”

- Archer, William and Charles. Heinemann. 1923. (This seems to be the ‘definitive’ translation – at least historically).

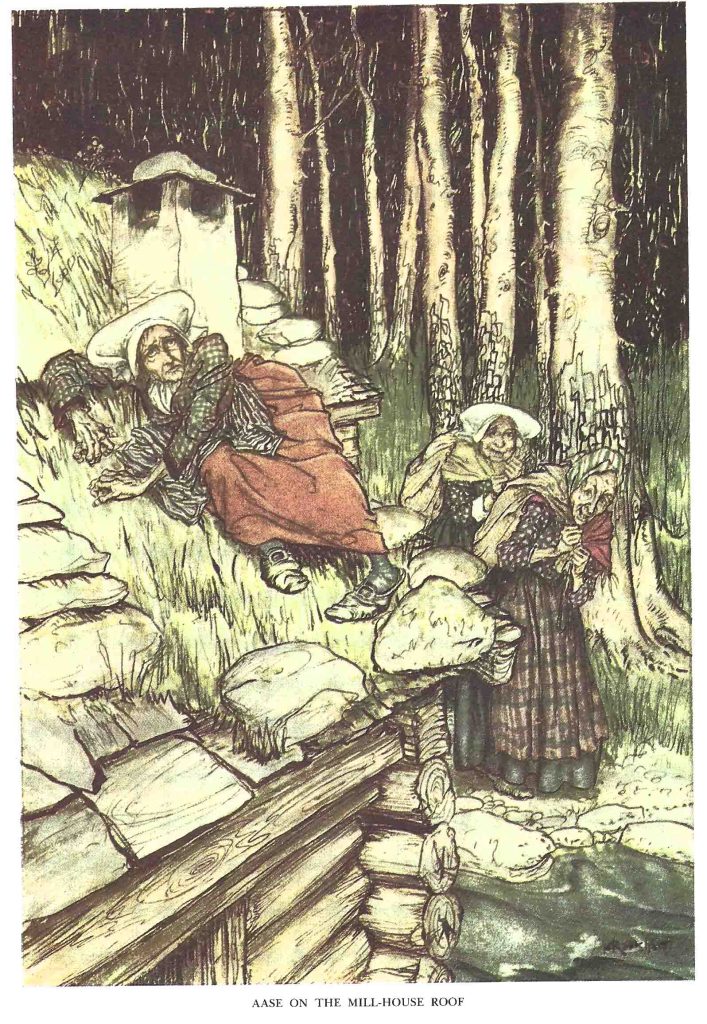

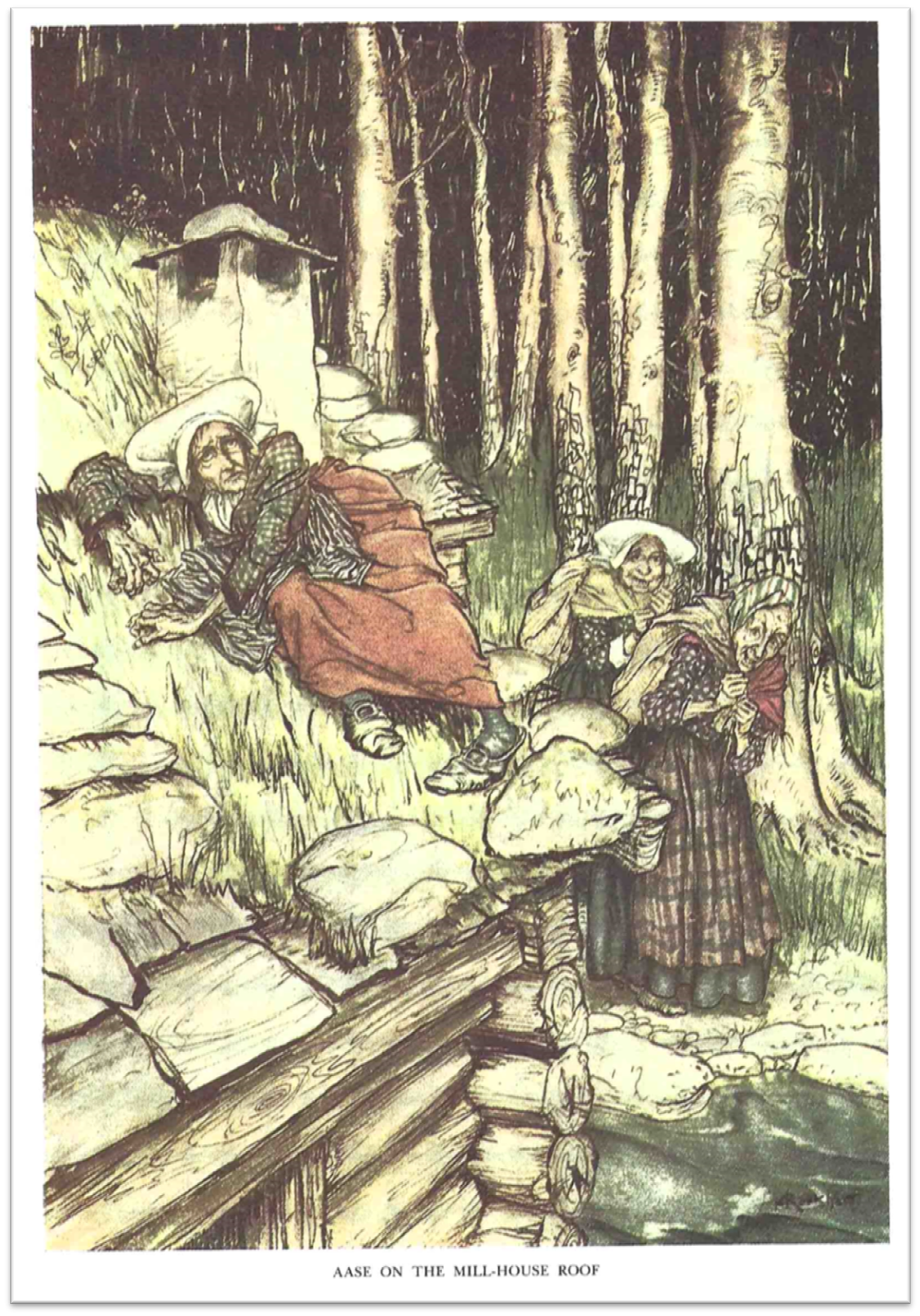

- Ibsen, Henrik, Peer Gynt. 1985. Translation by Farquharson Sharp, R. (first published 1921, and 1936). Harrap, London. (this publication is perhaps ‘dated’, but presents great illustrations by Arthur Rackham).

- McGuinness, Frank. 1990. (a ‘modern’ translation).

- Northam, John.

I found the following translation by Northam online, written in a more modern language, and also rhymed. Thus, I sometimes also refer to Northam’s translation, but also refer to the translations by Farquharson Sharp and the Archers.

- Peter Watts: 1966. His translation includes an introduction.

Link to Northam’s translation

Northam, John. Peer Gynt – A Dramatic Poem[10]

I will include Northam’s translation of Act One, Scenes 2 and 3. For Act Two, Scenes 1-5, I will use Farquharson Sharp’s translation, which I have found online.[11] Many of the translations are unreliable, and leave things out, such as Farquharson Sharp. For Act 2, Scene 2 onwards, I will use Archers’ translation which I have also found online.[12] Hopefully, Archer will be more reliable than the other translators mentioned here. Of course, I could have included other translations, but as mentioned, my main aim is not to focus on Ibsen’s play, or the translations, but to showcase Mikhail Khristoljubov’s illustrations. Moreover, these ‘old’ translations are free, and sometimes ‘old is best’ – after all, they have translated Ibsen in the same era that Ibsen wrote the play, more or less; so apart from the fact that some of the archaic language may be inaccessible to the modern reader, they nevertheless seem more authentic. In this context, one can think of modern English translations of ‘old’ texts such as Shakespeare’s plays and the Bible. Such modern translations can often seem prosaic. Some of the ‘power’ of these ‘ancient’ texts is their opaqueness; that is, the old forms of language seem to imply a deeper meaning. This idea is exploited by religious diviners around the world. Clothing an idea in archaic language seems to give the idea more credence. Moreover, this principle is exploited by religious rulers to entrench their power, and justify the execution of opponents.[13]

Brief and cursory analysis of the translations

A quick evaluation of the above translations suggests that the ‘oldest is best’, at least concerning the five translations mentioned here; but as also mentioned, there are many other translations. But my plan is not to translate all of Peer Gynt or evaluate the ‘16’ translations, but to post what I have translated (Act One, Scenes One and Two), and the illustrations by the artist Mikhail Khristoljubov. In other words, this is an ‘unfinished project’; nevertheless, this does not mean that I can’t post/publish what I have done so far. But to return to the evaluation of the translations. The Archers’ translation seems to be superior to Farquharson Sharp’s. To be blunt, the modern translation by Frank McGuinness seems quite poor. Northam’s translation is undoubtedly a brave attempt, as he tries to imitate the rhymes of Ibsen’s dramatic poem. However, this is where we have the idea ‘lost in translation’. Northam’s striving for rhyme sometimes ignores the content of the original. Although rhyme and metre are important, surely content is more important? It is here the Archers’ seem to be more skilled. The ‘mill-house roof’ episode is obviously comical. But some of the translators miss this point. For example:

ANDRE KÆRRING

ÅSE! Se, – så høyt på strå?

ÅSE

Dette her vil lidt forslå;-

snart Gud bedre mig, jeg himler!

FØRSTE KÆRRING

Signe rejsen!

This extract from Project Runeberg (http://runeberg.org/peergynt/) seems to be written in the original, but I’m not certain. Whatever, the ‘meaning’ is not at first apparent. But there is an obvious play on words. For example, the pun on the word ‘himler’, meaning to ‘give up’, and look up towards heaven in desperation. In other words, there is a comical element intended by the author, which not all the translators manage to capture. Whereas, the Archers capture this comical moment:

SECOND WOMAN. “ÅSE! well, you are exalted!

ÅSE. This won’t be the end of it;

Soon, God help me, I’ll be heaven high.

FIRST WOMAN. Bless your passing!

This humoristic point is more or less lost in McGuinness’, Farquharson’s and Northam’s translations.

Peter Watts also translated “Peer Gynt”. I have to admit on re-reading my initial translation I have cast aside the idea of metre and mainly focused on writing a text that ‘makes sense’. In this process, I have heavily borrowed on Watts’ translation for Act One, Scenes One and Two.

On a cursory analysis of Watt’s translation, his seems to be far superior – to the others – at least in terms of modern understandability. He also manages to catch the humour of the episode with ÅSE on the millhouse roof:

SECOND WOMAN: Åse” You’ve gone up in life!

ÅSE: What good’s that to me? God help me.

I shall soon go up to heaven!

FIRST WOMAN: Pleasant journey!

Problems of translation

As mentioned above, there are translation problems, especially when trying to translate rhymed verse. Peter Watts discusses this in detail, so I will include his discussion of such problems which he discusses at the end of the introduction in his translation of “Peer Gynt”.

Peter Watts discusses the problems of translating “Peer Gynt”[14]

Unfortunately, it is almost inevitable that a translation must fall short of the original, and with a poem that the diminution is particularly glaring. Peer Gynt in its original Norwegian is in rhymed verse. It is gay, galloping verse, with rhymes that are often double or triple, and as ingenious and outrageous as any that Robert Browning or W. S. Gilbert ever devised. The lines are mostly in couplets but sometimes in quatrains. The metre is based on four stresses to a line, but with a varying number of syllables to the foot; iambuses, trochees, spondees, dactyls, and anapaests come tumbling over each other to give the poem a splendid vitality.

When Archer wanted to put the play into English, Ibsen wrote that he would rather have it left untranslated than rendered into prose. Certainly to rob the work of its varied metres would be to take most of the fun out of it on the other hand, it would be possible to combine Ibsen’s complicated and witty rhyming with an even moderately accurate translation. I have therefore followed Archer in using unrhymed verse, keeping to Ibsen’s four-stressed line, that I have not always slavishly followed his exact scansion at the expense of the meaning in English. Indeed to compensate for the loss of Ibsen’s adventurous rhymes (and remembering A.E. Housman’s dictum that in English while ‘blank verse can be written in lines of ten or six syllables, a series of octo-syllables ceases to be verse if they’re not rhymed’). I have deliberately tended to vary the metre a little more than Ibsen does, in case the lines should settle down into monotony I have been especially free with Ibsen’s metre when he writes in quatrains of alternate lines of eight and seven syllables – a form that in English is hard to bear without rhyme.

The translation

As mentioned, I translated the initial pages paying attention to metre. But beyond the point where ÅSE says, “Oh, you brawler! You’ll send me to my grave with your ways!” (line 234); as mentioned, I have more or less ignored rhyme and metre, and focused mainly on content.

What is a good translation?

When I studied translation at Oslo University under Professor Chaffey at the end of the twentieth century, one of the syllabus books was Peter Newmark’s excellent, A Textbook of Translation (1988). Newmark asks the question: “What is a good translation?” He lists possible alternatives; one of these is that “a translation should be faithful to the original”. Of course, this seems a reasonable principle, especially in the world of official interpretation. However, there are many types of translation. This is the key here. What is the purpose of the translation? Obviously, if you are translating a tourist brochure, then you can have a fairly ‘free’ translation which is not necessarily faithful to the original. Another alternative was, “Should a translation improve on the original?” Of course, all these questions are dependent on the requirements of the clients. If the client is a poor writer in his/her own language, and often makes grammatical, content and logical errors, then the translation should improve on the original; that is, if the client does not object. When I do a translation, I often collaborate with two or three other professionals. So, it goes without saying that a translation can be better than the original. In fact, it is often not so much a translation, but rather a rewriting.

But to return to the point of translating Ibsen. First of all, I do not have a ‘client’, as this is something I am doing on the basis of my own interests. The other aspect here is ‘respect for the original’. Thus, the eleventh commandment states that canonical writers such as Shakespeare and Ibsen should never be critically evaluated as they are ‘untouchable Gods’ within their sphere. Of course, this is just silly. The point I’m trying to make here is that translators (in the case of canonical writers) often have too much respect for the original text. To cut to the chase – my main aim is not so much to remain ‘faithful’ to Ibsen, but to write a text that makes sense to the general modern reader.

Intertexts

The Norwegian-Scot Grieg[15] wrote the music to the Norwegian-Scot[16] Ibsen’s magnificent play.[17] See the ‘Prelude’ below for a description of the music “Peer Gynt”, as well as an MP3 recording of the music.

An audio version of the play in English

For an audio version of the play in English see the following link:

https://librivox.org/peer-gynt-by-henrik-ibsen/

Aim of translation

As mentioned, the aim of my translation of Acts One, Scenes One and Two, and the inclusion here of the translation of the rest of the play by John Northam and the Archers, is to provide a vehicle for the showcasing of the illustrations to the play by the artist Mikhail Khristoljubov. In this context, I will also include illustrations by other artists, such as Edward Munch and Arthur Rackham (publication permission pending).

As mentioned, the aim of my translation of Acts One, Scenes One and Two, and the inclusion here of the translation of the rest of the play by John Northam and the Archers, is to provide a vehicle for the showcasing of the illustrations to the play by the artist Mikhail Khristoljubov. In this context, I will also include illustrations by other artists, such as Edward Munch and Arthur Rackham (publication permission pending).

Illustrations

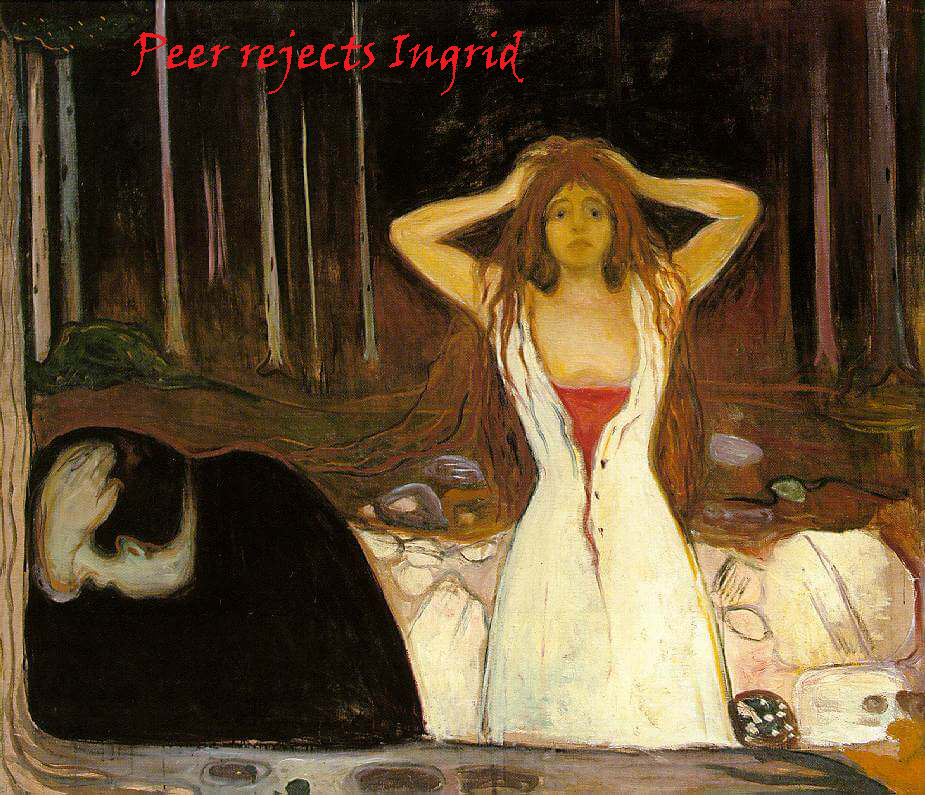

I imagined it would be a fairly simple thing to reproduce Ibsen’s play “Peer Gynt” in English with illustrations by Mikhail Khristoljubov, and a few illustrations by Edvard Munch, and Arthur Rackham, and post them online. Wrong again! Searching the internet soon made it evident there were hundreds of illustrations of the play; moreover, Munch seems to have been greatly inspired by the play and produced countless drawings, and paintings such as “Ashes” which seem to be only indirectly related to the play. As mentioned, my original intention was to post the drawings on internet of Mikhail Khristoljubov in order to ‘finalise’ the unfinished project we started on around the turn of the millennium. My plan was to do this in one or two days, or at the most one week. But I see now that this could carry on for a long time, so I will have to be selective in using the drawings of Munch and others, and this will mainly be arbitrary due to my limited time-frame.

Brief critical evaluation of the play

I am not the one to critically evaluate this play, being ‘unqualified’ in many ways.

Nevertheless, I have spent so much time working with this play that it would be presumptuous of me not to say something! In fact, I will heavily borrow from other sources such as Wikipedia.

First of all, this is a complex text combining many ideas, styles, forms and so on, without, it seems, having an overall ‘central message’. One might even go as far to say that it is some kind of ‘stream of consciousness’, where Ibsen plays around with many ideas – literary, dramatic, political, social, and so on. Of course, this presents another problem – how many people are familiar with the political and social issues of the period in which the play was written (1876)? And how many people are familiar with Norwegian dramatic and poetic conventions of the mid- nineteenth century? How many people are familiar with the Norwegian folklore of the nineteenth century? And so on, and so on.

Despite all these hindrances to understanding, the modern reader (in 2022) can still find elements that appeal. Of course, the poem was written in verse. It is often difficult or even impossible to translate poetry because poetry is so closely connected to the language in which it is written as well as the culture. Thus, non-Norwegian readers are hampered from achieving a full understanding of the play. But before we get carried away – Ibsen didn’t write in Norwegian, but in Danish.[18] If you buy a book by Ibsen today in a Norwegian bookshop, the language will undoubtedly have been violated in the name of ‘modernization’; of course, this is no more than a euphemism for ‘lack of respect’ for the language of the author, and an attempt to appropriate a Danish-Norwegian artefact so that it is solely a Norwegian artefact. In other words, this involves re-writing literary texts for nationalistic means. The point I’m trying to make here is that the present-day reader of Ibsen in Norway is also a ‘stranger’ to the language of Ibsen; one might go as far to say that a Dane can understand Ibsen better than a Norwegian.

From Wikipedia[19]

Peer Gynt chronicles the journey of its title character from the Norwegian mountains to the North African desert and back. According to Klaus Van Den Berg, “its origins are romantic, but the play also anticipates the fragmentations of emerging modernism” and the “cinematic script blends poetry with social satire and realistic scenes with surreal ones.” Peer Gynt has also been described as the story of a life based on procrastination and avoidance.

(…)

Ibsen wrote Peer Gynt in deliberate disregard of the limitations that the conventional stagecraft of the 19th century imposed on drama. Its forty scenes move uninhibitedly in time and space and between consciousness and the unconscious, blending folkloric fantasy and unsentimental realism.

Wikipedia continued:

Analysis

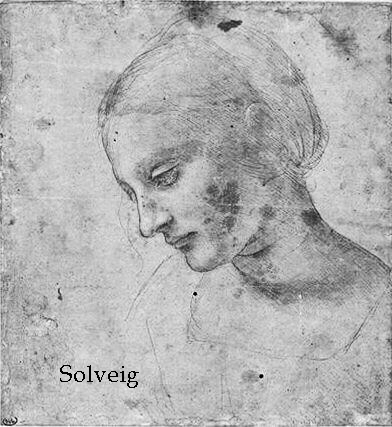

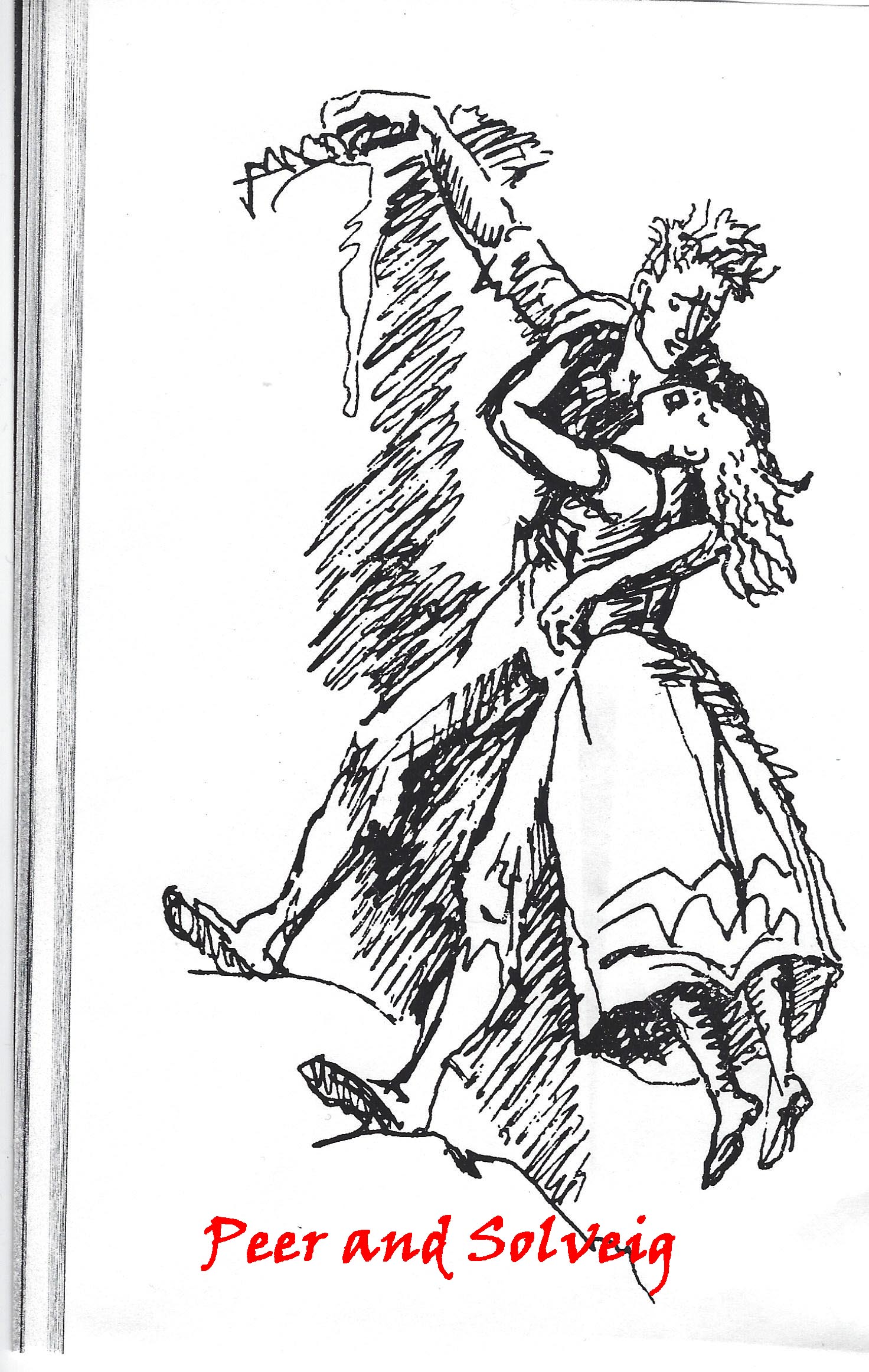

Klaus van den Berg argues that Peer Gynt … is a stylistic minefield: Its origins are romantic, but the play also anticipates the fragmentations of emerging Modernism. (…) The irony of isolated individuals in a mass society infuses Ibsen’s tale of two seemingly incompatible lovers – the deeply committed Solveig and the superficial Peer, who is more a surface for projections than a coherent character. The simplest conclusion one may draw from Peer Gynt, is expressed in the eloquent prose of the author: “If you lie; are you real?”

The literary critic Harold Bloom in his book The Western Canon has challenged the conventional reading of Peer Gynt, stating: Far more than Goethe’s Faust, Peer is the one nineteenth-century literary character who has the largeness of the grandest characters of Renaissance imaginings. Dickens, Tolstoy, Stendhal, Hugo, even Balzac have no single figure quite so exuberant, outrageous, vitalistic as Peer Gynt. He merely seems initially to be an unlikely candidate for such eminence: What is he, we say, except a kind of Norwegian roaring boy? – marvellously attractive to women, a kind of bogus poet, a narcissist, absurd self-idolator, a liar, seducer, bombastic self-deceiver. But this is paltry moralizing – all too much like the scholarly chorus that rants against Falstaff. True, Peer, unlike Falstaff, is not a great wit. But in the Yahwistic, biblical sense, Peer the scamp bears the blessing: More life.

(…)

The character Jon Gynt is considered to be based on Ibsen’s father Knud Ibsen, who was a rich merchant before he went bankrupt. Even the name of the Gynt family’s ancestor, the prosperous Rasmus Gynt, is borrowed from the Ibsen’s family’s earliest known ancestor. Thus, the character Peer Gynt could be interpreted as being an ironic representation of Henrik Ibsen himself. There are striking similarities to Ibsen’s own life; Ibsen himself spent 27 years living abroad and was never able to face his hometown again.

Some of my brief observations

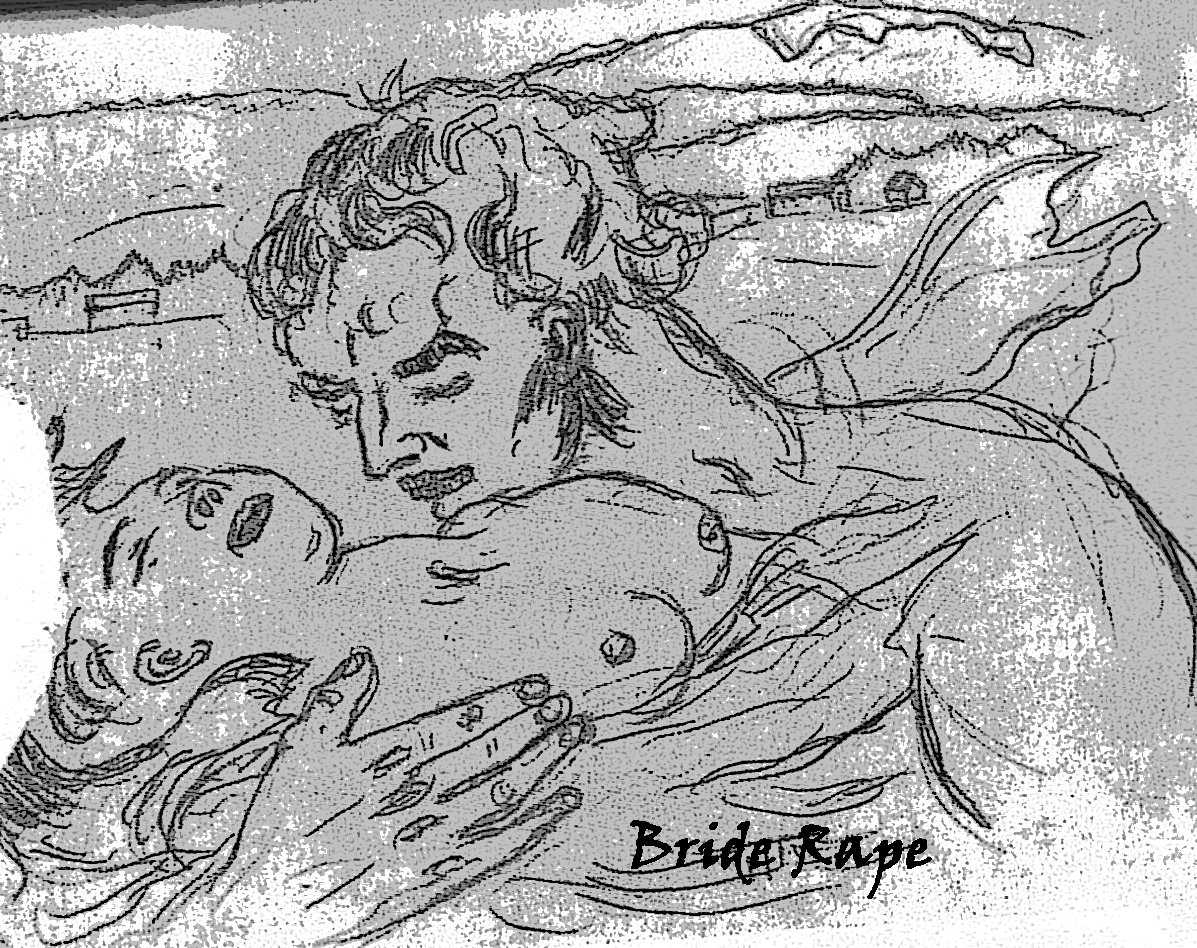

Of course, as mentioned, I should be the last person in the world to evaluate Ibsen’s “Peer Gynt” as Norwegian literature is not my speciality. However, while translating and reading the play, I can’t help but refrain from having ideas about the play. For instance, on reading the beginning of Act II, it would be naïve to imagine that the character of Peer Gynt can be wholly equated with the character of the author. Nevertheless, one can’t ignore the fact that Peer Gynt’s thoughts are also the thoughts of the author, albeit indirectly. First of all, Act Two could never have been written by a woman. Why? Because the author adopts a ‘whore and Madonna perspective’. Thus, Peer willingly abuses (rapes) Ingrid, but once he has ‘had his way with her’, he does not desire her anymore. He only desires the ‘underage’ and ‘saintly’ Solveig. This idea has obsessed men for centuries it seems, and still obsesses them today; that is, the ‘whore and Madonna’ idea, and the idea that all women ‘wish to be raped’. In other words, is Ibsen promoting misogynism or satirising it? Satire is a dangerous tool, as it can often be interpreted literally, that is, as reinforcing prejudices. The example that springs to mind here is the satirist TV sitcom, “Fawlty Towers”.[20] Basil Fawlty is a racist and misogynist. He constantly abuses his Spanish (‘third world employee’) Manuel. It has been my experience that Norwegians (and most probably also British people, although of course not Spanish people) laugh at Manuel rather than Fawlty, and feel exonerated if they want to abuse their Spanish ‘servants’ when taking their holidays in Spain.

In other words, Ibsen does not make his position clear during the course of the play (at least to the modern reader). I might even go as far to say that the play functioned as a kind of sexual-psychological vehicle for his own sexual hang-ups. In other words, Henrik Ibsen is ‘hiding’ behind Peer Gynt.

Is Ibsen promoting ideas that it is okay to abuse women, or is he criticising these ideas. This is by no means clear in the play. This play may have been written some 150 years ago, nevertheless, it is highly topical today. The abuse, rape and torture of women and other genders is used by various oppressive ‘male’ regimes today to consolidate their power, such as Afghanistan, Iran, Russia, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, and many others. Regarding the harmful beliefs that perpetuate violence against women and girls, this has been well-documented by Oxfam.[21]

As mentioned, the character of Peer is obviously presented satirically – but this does not alter the fact that the author is able to give this description – in other words, it is part of the author’s male mental make-up – a kind of ‘Jekyll and Hyde’ aspect.

As mentioned elsewhere, my aim here is not to give a full translation of Ibsen’s play, or write a full critical analysis, for example, regarding its erotic content. There are many others who have commented on the erotic elements of Ibsen’s play. A brief search on the Internet provides lots of evidence.[22]

Of course, let’s face it – I am being a little unjust here. Ibsen uses folk culture to examine the human psyche. H.C. Anderson also utilised folk culture as a means of commenting on more ‘universal (and current) truths’, such as the story of the “Emperor with no Clothes” (Andersen, 1837). In other words, Ibsen and Andersen were both ahead of their time in the re-writing of folk tales and legends. This, became popular in the ‘liberated’ second half of the twentieth century, as demonstrated by Angela Carter’s rewriting of fairy tales in her collection of stories “The Bloody Chamber” (1979).

Ibsen, Anderson and Carter had different agendas; nevertheless, they had in common that they utilised folk culture to examine human life contemporarily. This contrasts with the work of folklorists such as the Brothers Grimm (Germany), and Asbjørnsen and Moe (Norway) who were funded by their governments (at least in the latter case) to promote a national identity. This was not an isolated phenomenon but can be found in the cultural works of various European artists and writers.

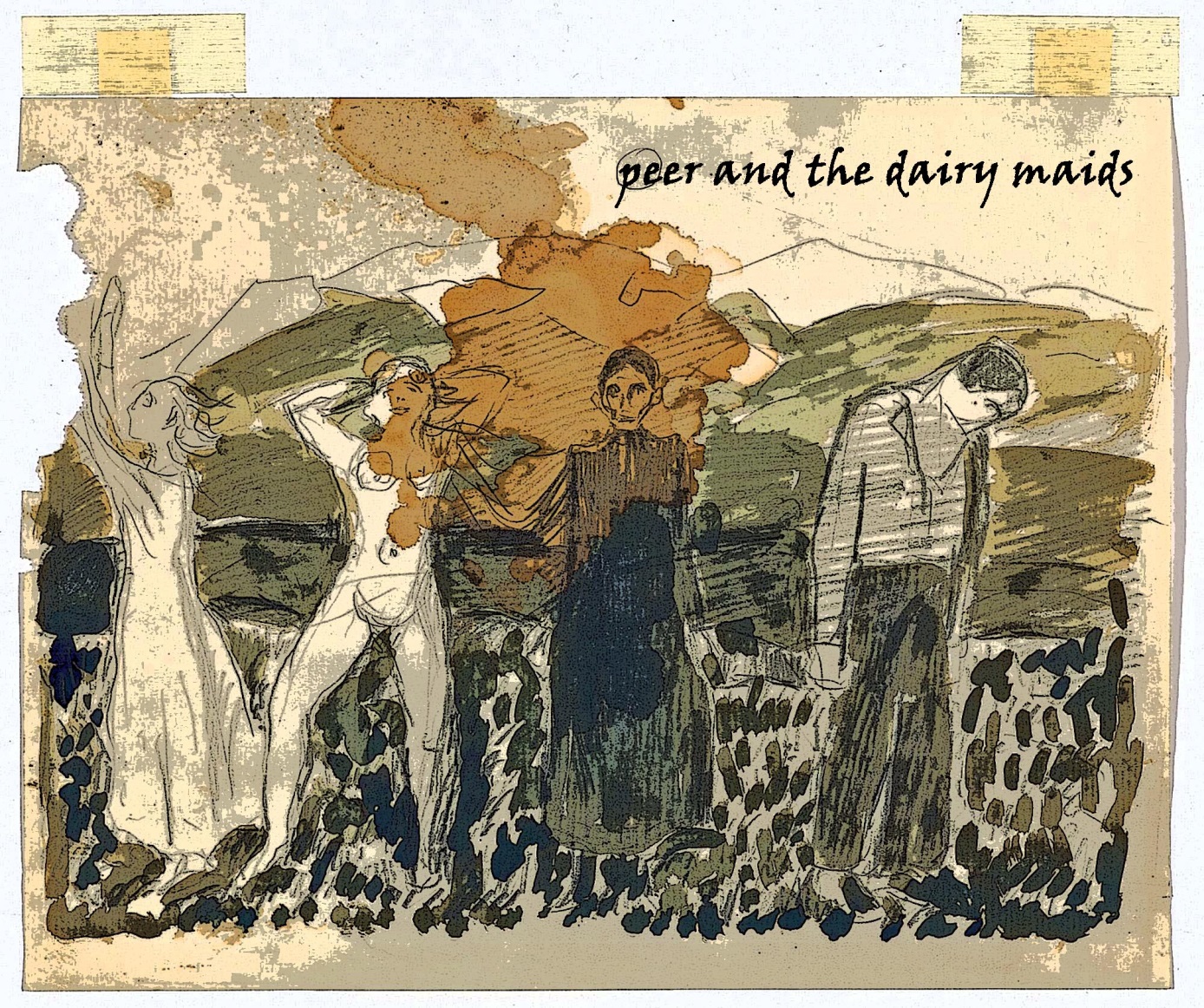

Erotic elements in Peer Gynt

Despite all the poetry and folklore, Peer could star in a modern-day Westerner’s sexologue about a trip to Thailand. Thus, in Act II Scene 3, he is accosted by three dairy maids ‘on-heat’ – in other words, a kind of man’s sexual fantasy.

Folk culture, Peer Gynt and ‘the Fool’

Some commentators have pointed out the similarity of Peer Gynt to the ‘Ash Lad’ (Askeladden) in Norwegian folklore. Of course, the ‘Ash Lad’ is not unique to Norwegian folklore. I have translated folk tales from the Russian about ‘Yemelya’ who is a similar character (see link in footnote).[23]

But we are entering into a very complex discussion here of which I know very little about, that is, ‘the Fool in cultural texts’. As mentioned, Peer Gynt can be related to the character of the ‘Ash Lad’ in Norwegian folktales. There are many types of ‘fools’ in cultural and literary texts. The Ash Lad may be viewed as a so-called “serendipitous fool.” That is, a simpleton, who, in the end, wins big, usually a princess or a kingdom, or wealth. Of course, Ibsen seems to have some kind of contradiction here, because ‘the fool’, like the ‘picaresque hero’ is often of a lower social class. However, I do not intend to get embroiled in a discussion of the ‘picaresque’ here; but the first novel of European literature was a picaresque one, Don Quixote; but he was not from the lower classes

but a nobleman.

‘Politically correct’ Henrik?

I haven’t searched secondary sources, but although we love the ‘socially aware’ Henrik, like his anti-hero Peer, Henrik is a ‘red neck’ at heart, that is, a Norwegian ‘cuntry bumpkin’. I don’t intend to delve into all his issues here, but seem to remember that he is a victim of the traditional male viewing women as whores and Madonnas (Anitra vs Solveig, and so on). I also seem to remember on reading about him in the past that he had a predilection for young girls – but I don’t want to delve into that here but just mention it in passing (see footnote).[24]

Erotic elements in Peer Gynt

Whore and Madonna

As briefly mentioned above, men are traditionally obsessed by the idea of ‘whore and Madonna’. Of course, a man can only have one ‘Madonna’ – a kind of sexual substitute of his mother (without going into a Freudian analysis). Thus Peer has only one ‘Madonna’ – Solveig. But he has many ‘whores’.

As mentioned elsewhere here my aim is not to translate the whole play, or thoroughly analyse it (God forbid!). Nevertheless, one can’t but help but have one’s own thoughts as one reads through the play. I haven’t read any of the secondary literature about the play (apart from the ones mentioned in the internet search above – which I haven’t read). But I would like to wager that many critics have focused on the sexual-psychological aspect of the play; that is, the play is not only a ‘discussion’ of various social, cultural and political topics, but it is also inadvertently a discussion of Ibsen’s ‘repressed’ sexuality, or further, a discussion of man’s sexuality in the nineteenth century. In other words, he uses the vehicle of Peer  Gynt (whom he seems to be mainly critical of) to discuss implicitly his own sexual hang-ups. Thus, he lists up a bevy of ‘whores’ in the play: Ingrid, the woman in green, Anitra, the three herd girls, and so on.

Gynt (whom he seems to be mainly critical of) to discuss implicitly his own sexual hang-ups. Thus, he lists up a bevy of ‘whores’ in the play: Ingrid, the woman in green, Anitra, the three herd girls, and so on.

This often verges on the erotic-comical. The three sæter girls (herd girls) that lure men into having sexual encounters. I didn’t find the source for this legend, but I seem to remember reading it somewhere.

Women want to be raped

As mentioned above in a footnote referring to the Oxfam website, there are many harmful beliefs that perpetuate violence against women and girls; one of these beliefs is that women want to be raped. This idea is indirectly reinforced in the play with Peer Gynt’s rape of Ingrid. After she has been raped, she clings to him, but he casts her off, because he is eroticizing in his mind about possessing the virgin Solveig.

Of course, Ibsen does not freely admit this, because of his socio-political conscience. Peer Gynt is Ibsen’s alter ego. Henrik Ibsen is actually Doctor Henrik Jekyll, and Peer Gynt is Mr Hyde.[25] Ibsen is thus able to live out his sexual fantasies through the character of Peer. Peer rapes the bride (Act One). After the rape, Ingrid clings to him (implying she wanted to be raped by a strong and handsome buck), but he rejects her, as his mind is still dwelling on the ‘underage Solveig’ and her innocent demeanour (‘clasping her prayer book’ with downcast eyes like da Vinci’s Madonna).

Peer sexually ‘expires’ many times throughout the course of the play – with Ingrid, the herd girls, the woman in green and Anitra. But towards the end of the play with Solveig, he expires literally in a kind of sexually satisfying death:

“I will cradle thee, I will watch thee;

Sleep and dream thou, dear my boy!”

(Act Five, Scene 10)

That is, the last lines of the play when he dies being cradled by his virginal love.

Fornicating with trolls with three heads – comical elements

In Act II, Scene III, Peer Gynt says:

“I’m a three-headed troll, and the boy for three girls!”

This surely must be a misprint. Which ‘head’ is he talking about, the ‘small head’ or the ‘big head’? Does he have three ‘little heads’ to ravish three young herd girls. This is perhaps wishful thinking on the part of Peer/Ibsen. This is a worn out theme of various porno sites – one man and several women. In practice this is somewhat difficult. A man can only have penile intercourse with one woman at a time. Of course, if one was some freak of nature with several penises (‘small heads’) then one could satisfy several women simultaneously. However, Ibsen does not elaborate on this point, so it just remains ‘wishful’ thinking.

Prelude

Peer Gynt composed by Edvard Grieg[26]

Peer Gynt, Op. 23, composed by Edvard Grieg is the incidental music to Henrik Ibsen’s 1867 play of the same name, written by the Norwegian composer Edvard Grieg in 1875.

The original score contains 26 movements: ]Movements indicated in bold were extracted by Grieg into two suites.

Act I

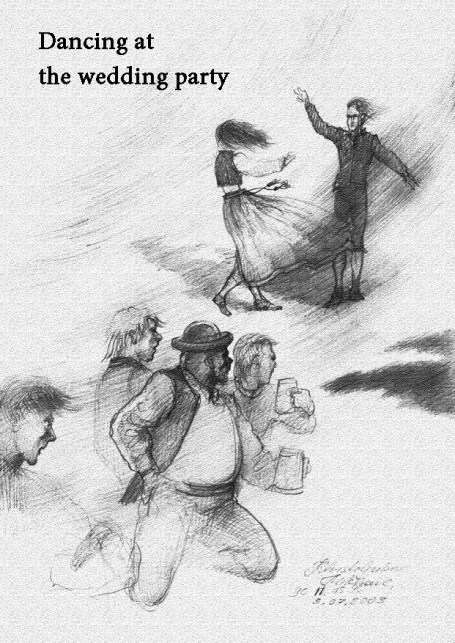

Prelude: At the Wedding

The Bridal Procession

Halling

Spring dance

Act II

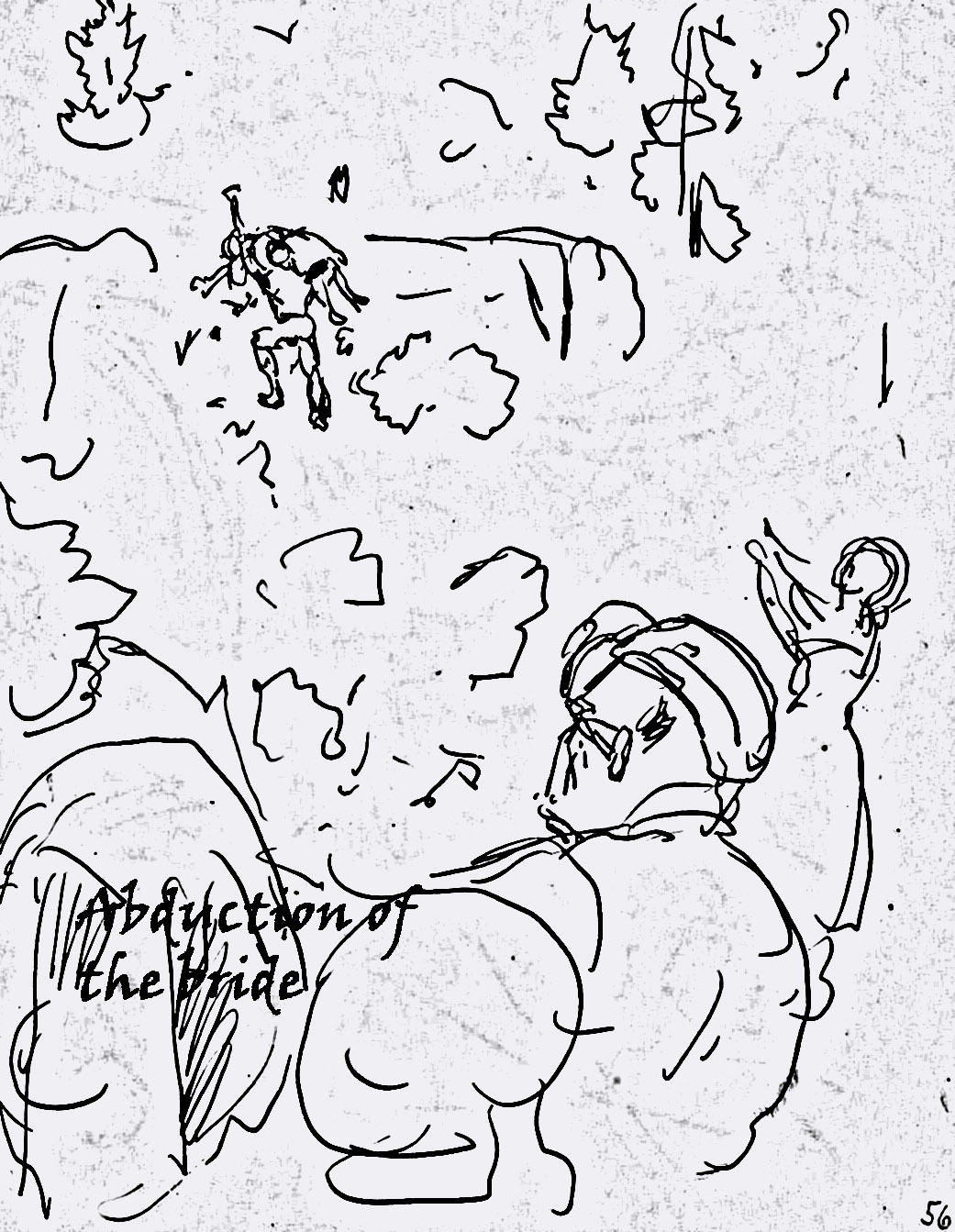

Prelude: The Abduction of the Bride. Ingrid’s Lament

Peer Gynt and the Herd-Girls

Peer Gynt and the Woman in Green

By His mount You Shall Judge Him

In the Hall of the Mountain King

Dance of the Mountain King’s Daughter

Peer Gynt hunted by the trolls

Peer Gynt and the Boyg

Act III

Prelude: Deep in the Forest

Solveig’s Song

The Death of ÅSE

Act IV

Prelude: Morning Mood

The Thief and the Receiver

Arabian Dance

Anitra’s Dance

Peer Gynt’s Serenade

Peer Gynt and Anitra

Solveig’s Song

Act V

Prelude: Peer Gynt’s Homecoming

Shipwreck

Day Scene

Solveig sings in the hut

Night Scene

Whitsun Hymn

Solveig’s Cradle Song

Peer Gynt[27]

CHARACTERS

ÅSE, a farmer’s widow

Peer Gynt, her son

Two Old Women with sacks of corn

Aslak, a smith

Wedding Guests, Steward, Fiddler etc.

A newly-arrived Man and Wife

Solveig and Little Helga, their daughters

The Farmer at Hægstad

Ingrid, his daughter

Bridegroom and his Parents

Three Herdgirls

Woman in Green

Dovre-King

Senior Troll, several similar. Troll boys and girls. A couple of witches. Gnomes,

elves, goblins etc.

Ugly Child

Voice in the dark

Bird Cries

Kari, a cottager’s wife

Master Cotton, Monsieur Ballon, Herrer v. Eberkopf and Trumpeterstraale, travelling

gentlemen

Thief and a Fence

Anitra, Slave Girls, Dancing Girls etc.

Memnon’s Statue (singing)

Sphinx of Gizeh (mute)

Begriffenfeldt, professor, Ph.D., director of the lunatic asylum in Cairo

Huhu, a language activist from the Malabar coast

Hussein, an oriental government minister

Fellah with the mummy of a king

Several inmates of the asylum, with their keepers

Norwegian Skipper and Crew

Strange Passenger

Priest

Funeral procession

Bailiff

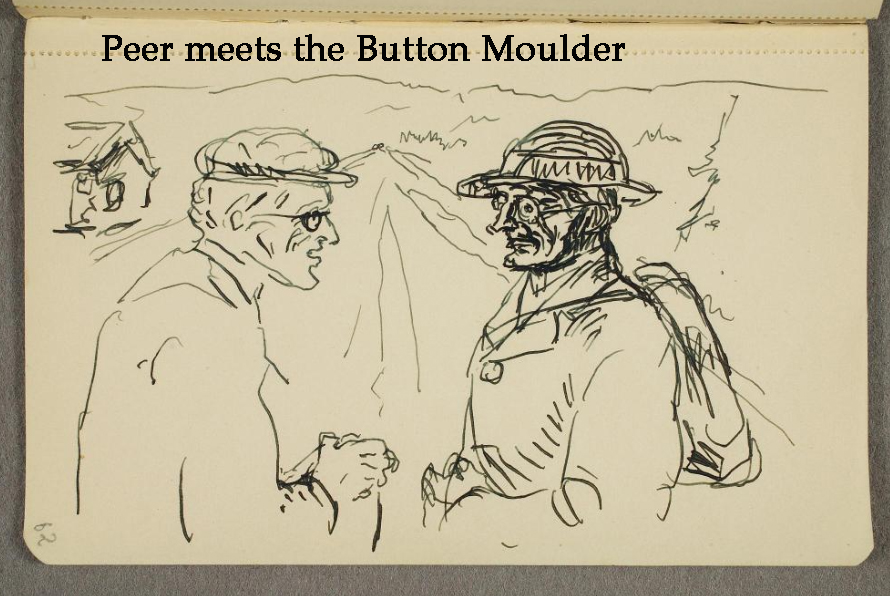

Buttonmoulder

Thin Person

_________

(The action, which begins at the start of this century and ends at about our own time, takes place partly in Gudbrandsdal and the surrounding high country, partly on the coast of Morocco, partly in the Sahara desert, the asylum in Cairo, at sea, etc.)

Act I

Act I

Scene 1

(On a wooded mountainside near ÅSE’s farm. A river rushes down the hillside, and on its far bank stands an old mill. It is a hot summer’s day.

PEER GYNT, a well-built youth of twenty, comes walking down the path, followed by his mother, ÅSE, a small and slightly-built woman, who is scolding him angrily.)

ÅSE. Peer, you’re lying!

PEER. (without stopping): No, I’m not!

ÅSE. Well, swear it’s true then!

PEER. Why should I?

ÅSE: Hah. You don’t dare to!

It’s all stuff and nonsense!

PEER. (stops): It’s true – every blessed word!

ÅSE. (confronting him): Shame! How dare you face your mother!

First you take off to the mountains,

Gone for months at harvest time,

Hunting reindeer in the snow,

Come back home with clothes all torn,

With no game, without a gun,

Then to crown it all,

You shamelessly try to take me in

With a pack of huntsman’s tales!

Well, where did you find this buck?

PEER. West of Gjendin.

ÅSE. (laughs mockingly): Very likely!

PEER. It was a biting wind that blew;

Hidden behind a clump of alder,

He was scraping in the snow-crust for lichen –

ÅSE. (interrupts cynically) A likely story!

PEER. Holding my breath, I stood listening,

Heard the scraping of his hooves;

Saw the branching antlers,

So I carefully crept forward,

On my belly between the rocks.

Hidden ‘tween two rocks I watched,

By Jove! Such a magnificent buck,

So sleek and fat,

You never saw one like him!

ÅSE. Good heavens!

PEER. Bang! I fired!

Down the buck crashed to the ground!

The instance he fell,

I climbed astride his back,

Gripped him hard by his left ear,

Was about to plunge my knife

In his neck beneath the skull …

Hey! The wild beast bellowed madly,

Swiftly scrambling to his feet,

Lurching violently backwards,

He jerked the knife out of my hand;

Pinned my legs between his antlers,

Clamping me tightly like a vice;

Then with a sudden leap, he bounded

Right along the ridge of Gjendin!

ÅSE. (involuntarily) God help us!

|

|

PEER. Have you ever seen Gjendin ridge?

Stretching for about three miles,

Sharp its edge cuts like a scythe,

Steeply down on either side,

Down past slope and avalanche,

Straight across the screes of grey,

One can see on both the sides,

Down towards the lakes which sleep

Black and heavy, more than

Thirteen hundred ells[28] beneath.

Right along the ridge we two

Cut a passage through the weather.

Such a foal I never have rode!

Straight in front where we sped ahead,

Seemed to hang the blazing sun.

In between the lakes and us

Tawny backs of eagles hovered

In the vast and dizzy void,

Falling just like specks behind us.

Ice floes crashed against the shores,

Yet no murmur of the sound reached us,

Swirling misty shapes leapt like

Dancers, weaving and spinning around us,

Till all my senses were in turmoil!

ÅSE. (giddy) Oh, God help me!

PEER. Suddenly, near a sharply sloping spot,

Up jumped a grouse-cock,

From the crack where it had lain hidden,

Flapping, cackling, terrified, –

Right beneath the buck’s hoof on the ridge.

The buck took fright, turned half around,

Plunged off the ridge with a mighty leap,

Taking us both down towards the depths below!

|

|

|

|

|

|

(ÅSE reels. reaching for the trunk of a tree. PEER continues):

Black the mountain wall behind,

Under us the deep abyss!

First we clove through clouds of mist,

Then we split a flock of gulls,

They scattered in all directions,

Filling the air with their screeching.

Downwards we rushed, ever downwards!

Until below us something glistened

Whitish like a reindeer’s belly….

Mother, it was our own reflection,

Flying upwards from the glassy water,

While we darted downwards to meet the reflection

At the same mad rush of speed.

ÅSE. (gasping for breath) Peer! For God’s sake! Tell me quickly – what happened!

PEER. Buck from above, buck from below,

Clashed their antlers in a moment,

So that the foam lashed about us.

There we lay then, floating, splashing;

Buck he swam, I hung on behind;

After many endless hours we were

Able to reach the northern shore.

So I came home.

ÅSE. But what about the buck Peer?

PEER. He’s still there for all I know;

(snapping his fingers, turns on his heel and adds)

If you find him you can have him!

ÅSE. And you didn’t break your neck?

Or break both your legs?

Or rick your spine?

Praise and thanks be to God Almighty

For the way he saved my boy!

It’s true – you’ve torn your trousers though,

Still, that’s hardly worth a mention,

When you think of what might have

Happened to you after such a leap!

(she suddenly pauses, stares at him wide-eyed and open-mouthed; for some time she is lost for words, then at last she bursts out)

Oh, you spin a yarn like the devil!

God almighty, what a liar!

All this nonsense you’ve come out with,

I remember now that I first heard it,

When I was a lass of twenty.

That’s the tale of Gudbrand Glesne,[29][30]

Not of you!

PEER. Of us both.

Such a thing can happen twice you know.

ÅSE. (exasperated): Yes, of course a lie can be turned around

Then adorned with pomp and show,

Clothed in newly fashioned skin

So then none can see its meagre carcass.

That is what you’ve gone and done,

Made the tale so wild and grand,

Spruced it up with tawny eagles,

Not to mention other nonsense,

And then lying through your teeth

Filled me up with speechless dread

So at last I couldn’t make out

What’s true and what’s not!

PEER. If a man had talked like that to me,

I’d beat him black and blue.

ÅSE. (weeping) Would to God I lay a corpse

Deep asleep in the black cold earth!

Tears and prayers don’t affect you,

Peer you’re a wastrel and always will be!

PEER. Dearest pretty little mother,

Every word you’ve said is true;

Yet be happy and gay –

ÅSE. Hold your tongue!

How can I be happy

When my son is such a swine?

Shouldn’t I be deeply hurt?

Me, a poor defenceless widow,

Always to be put to shame?

(starts weeping again)

What’s the family got to show

From your granddad’s days of riches?

Where are all the sacks of coin

Left us by old Rasmus Gynt?

Yes, your father gave them wings,

Scattered it all around like grains of sand,

Buying land in every parish,

Riding around in a gilded carriage.

And where’s the money he squandered

At the famous winter-banquets,

When the guests sent glass and bottle

Smashing on the wall behind them?

PEER. Where is last year’s snow?

ÅSE. Hold your tongue and don’t talk back!

Look at the farm! Every other

Window frame is broken and stuffed with rags!

Hedges, fences, need repairing;

Cattle left out in all weather,

Fields and meadows they lie fallow,

Every month the bailiff visits –

PEER. Enough of your old woman’s prattle!

Luck may sometimes fail you,

But then come back another day!

ÅSE. Salt is now strewn where once it was fertile.

Lord, but you are a fine one, you are!

Just as impudent and cocky still!

Just as jaunty as the day when the parson,

Coming here from Copenhagen,

Asked what your name was,

Then saying the name Peer Gynt

Was a name fit for a prince,

Swearing princes from where he came from

Couldn’t boast of the talents you had;

So your father gave him a horse,

With a sledge as well, in thanks

For his friendly flattery.

Hah! everything was so fine then!

Parsons, officers and all the rest,

Dropped in, especially at meal times,

Ate and drank till they nearly burst.

But a friend in need is a friend indeed.

But no-one comes here anymore,

Not since the day when “Money-Bags John”

Went away with his pedlar’s sack.

(She dries her eyes with her apron.)

You’re a great big strapping fellow,

You should stand like a pillar of strength,

Helping your poor old mother,

Looking after the farm, and looking after the

Little that is left of your inheritance.

(starts crying again)

Heaven knows, it’s little use

You have been to me, you lout!

When you’re at home, you’re by the fireside,

Poking at the coals and embers;[31]

Among the local folk you scare the

Girls from the assembly room,

Picking fights with every lout,

Making me into a laughing stock.

PEER. (leaving her) Leave me alone.

ÅSE (following him) Wasn’t it you who

Was the worst amongst the rabble

In the mighty rough and tumble

The other day at Lunde,

Where you fought like some rabid dog?

Wasn’t it you that broke

Blacksmith Aslak’s arm,

Or, at the very least, wrenched

One of his fingers out of joint?

PEER. Who has told you such nonsense?

ÅSE. (in a temper) The cotter’s wife, she heard the yelling!

PEER. (rubbing his elbow) Yes, but in truth, it was me doing the yelling.

ÅSE. You?

PEER. Yes mother, – it was me that got beaten.

ÅSE. What d’you mean?

PEER. Well he’s a burly fellow, you know.

ÅSE. Who is?

PEER. Aslak of course.

ÅSE. Pah! You make me want to spit!

Letting such a worthless sot,

Just a boozer, and a toss pot

Like him, give you a thrashing.

(she starts crying again)

So much shame I’ve had to suffer;

But for this to happen to me

Is the worst mockery of all.

Just because he’s so strong,

Must you be so weak?

PEER. Hammer or be hammered, it makes no odds,

Either way you’d start your yammering.

(he laughs)

Don’t worry mother –

ÅSE. What? Have you been lying again?

PEER. Well, just this once.

Come and wipe those tears away.

(He clenches his left hand)

See this. It was with this tong

That I bent the blacksmith double;

While my right fist was my hammer –

ÅSE. Oh, you brawler! You’ll send

me to my grave with your ways!

PEER. No; you’re worth something better;

Twenty thousand times better!

My dear little old ma,

Just trust my word,

The whole village will do you honour one day,

Just wait until I have done

Something really marvellous!

ÅSE (sighs exasperated). You!?

PEER. Who knows what can happen?!

ÅSE. If only you were so smart,

You can’t even sew a patch

To fix the hole in your breeches!

PEER. (heatedly) You’ll see, I will become a king, an emperor even!

ÅSE. My God, he’s losing the little wit he has!

PEER. I will! Just give me time!

ÅSE. Indeed, surely one day you’ll be a prince!

PEER. Just you wait and see!

ÅSE. Just keep quiet and stop your blethering!

You’re as mad as mad can be!

But yet, it’s true, something might have become of you,

If you weren’t always carrying on with your lies and dreams!

The Hægstad girl was fond of you.

You could easily have won her,

If you had played your cards right.

PEER. Do you think so?

ÅSE. Her old father is feeble-minded,

And doesn’t have the strength to oppose her wishes.

He’s obstinate enough though,

But it’s always Ingrid who rules the day.

Wherever she walks, step by step,

The old man follows doddering after.

(she starts crying again)

Such a richly dowered girl,

Heir to her father’s lands, just think of it!

You could have had her if you’d wanted to,

She could have been your bride.

You could have been dressed finely like a bridegroom,

But now you just roam around here,

In dirty rags and tatters.

PEER. Very well, I’ll take her for my bride!

ÅSE. What do you mean?

PEER. I’ll go to Hægstad and woo her!

ÅSE. Poor you! That courting road is barred to you!

PEER. What do you mean?

ÅSE. While you were in the Western hills, riding bucks,

She’s become engaged to Mads Moen.

PEER. What? That silly fool?

ÅSE. Ay. She’s taking him as her husband!

The moment is lost. She’s betrothed to him.

PEER. Wait for me here,

I’ll harness the horse and cart.

(just about to leave)

ÅSE. Save such nonsense.

The wedding’s taking place tomorrow –

PEER. Pooh; I’ll go there this evening!

ÅSE. What! Do you want to make things worse?

Inviting everyone’s scorn?

PEER. Take comfort. Everything will go well.

(laughing and shouting)

Mother! We won’t bother taking the cart;

And we haven’t got time to fetch the mare.

(picks her up)

ÅSE. Let me go!

PEER. No, I’ll carry you in my arms

To the wedding courtyard!

(wades out into the river)

ÅSE. Help! Lord have mercy!

Peer! We’ll drown –

PEER. Oh no. I’m destined

To have a more glorious death—

ÅSE. Sure!

You’ll surely end up on a gallows in the end!

(pulling his hair)

Oh, you beast!

PEER. Keep still,

The bottom’s so slimy and slippery here.

ÅSE: Ass!

PEER. Just keep using your tongue,

Words never hurt anyone.

Watch out, it’s getting more difficult underfoot –

ÅSE. Don’t let go of me!

PEER. Hi, watch out!

Let’s play ‘Peer and the buck’; –

(galloping)

I’m the buck, you’re Peer!

ÅSE. How will all this end?!

PEER. You see, we made it in the end!

(He reaches the other bank)

Then just give your buck a nice kiss;

As thanks for the ride –

ÅSE. (boxes his ears). That’s the thanks for the ride!

PEER. Ow! That was poor payment!

ÅSE. Let me go!

PEER. First, we’ll go to the wedding.

Be my advocate. You’re smart;

Talk to him, the old fool;

Tell him Mads Moen is a good-for-nothing –

ÅSE. Let me go!

PEER. And then tell him what a fine lad Peer Gynt is!

ÅSE. Yes, you can count on that!

I’ll give you a pretty testimonial.

In every detail;

All your devil’s tricks,

I won’t leave anything out!

PEER. What!?

ÅSE. (kicks him angrily) I won’t let up,

Until they’ve set the old dog on you,

As if you were a tramp!

PEER. Then I’ll have to go on my own.

ÅSE. Yes, but then I’ll follow you!

PEER. Dear mother, you’re not strong enough.

ÅSE. I’m not? I’m in such a rage

That I could crush rocks to powder!

I could make a meal of flints!

So put me down!

PEER. Only if you promise –

ÅSE. I’ll promise nothing!

I’ll tell everyone at Hægstad what kind of bad sort you are!

PEER. Then you’ll have to stay here.

ÅSE. Never! I’m coming too.

PEER. No you aren’t.

ÅSE. What, how are you going to stop me?

PEER. I’ll put you up on the mill-house roof.

(He lifts her up on to the roof of the mill-house, she screams)

ÅSE. Lift me down!

PEER. Well, if you’ll listen to sense then?

ÅSE. Nonsense!

PEER. Dear mother, I beg you.

ÅSE. (she throws a sod of turf thatch at him)

Lift me down this instant Peer!

PEER. If only I dared, I surely would. (Goes closer)

Remember to sit still and quiet.

Don’t sprawl and kick about;

Don’t tug and tear at the roof shingles,

Otherwise you might get hurt;

You might fall down.

ÅSE. You beast!

PEER. Don’t sprawl and squirm up there on the roof.

ÅSE. You’re no child of mine, changeling![32]

PEER. Fie, mother!

ÅSE. Shut up!

PEER. You ought to give me your blessing for my venture.

Will you?! Well?

ÅSE. I ought to thrash you!

Great lumpkin that you are!

PEER. Well, goodbye dear mother!

Be patient; I won’t be long.

(He leaves, but lifts his finger in warning, and says:)

Careful now, don’t kick and sprawl up there! (He leaves)

ÅSE. God help me, he’s leaving!

Buck-rider. Liar!

Hey, listen to me! –

No, now he’s gone over the meadow! (Shrieks)

Help! I feel giddy!

Scene 2

(Two old women with sacks on their backs come down the path towards the mill-house.)

FIRST WOMAN. Lord! Who’s that shrieking?

ÅSE. It’s me!

SECOND WOMAN. ÅSE! You seem to have gone up in the world.[33]

ÅSE. And that’s not the end of it; I’ll soon be heaven-high and bound.

God help me, I feel faint!

FIRST WOMAN. Bless your passing then!

ÅSE. Get a ladder;

I want to get down from here!

Damn my blasted son!

SECOND WOMAN. Your son?

ÅSE. I can tell you,

You see how he behaves so badly!

FIRST WOMAN. Well, we’ll bear witness.

ÅSE. Just help me down from here;

I have to journey to Hægstad.

SECOND WOMAN. Has he gone there?

FIRST WOMAN. Then you can get revenge;

Because Aslak Smith is also going there.

ÅSE. (wringing her hands) Oh God help my poor boy;

They’ll take his life in the end!

FIRST WOMAN. Well maybe that’s his fate in this life.

Comfort yourself that what will be will be.

SECOND WOMAN. She’s clean out of her mind. (Calls up the hill)

Eivind, Anders! Hi – come down here quick!

A MAN’S VOICE. What’s wrong?

SECOND WOMAN. Peer Gynt has put his mother up on the roof of the mill-house![34]

|

|

|

|

Scene 3[35]

(A small hill with bushes and heather. A public road runs behind it, separated by a fence)

(PEER GYNT, from a path, hurries to the fence, stops and scans the view)

PEER There it is, Hægstad. Not far to go. 380

(half-climbs the fence and then hesitates)

I wonder if Ingrid’s at home still or no?

(shades his eyes and surveys)

No. Wedding guests swarming like gnats down the track.

Hmm; maybe it’s better that I should be turning.

(steps down again)

There’s always the laughter behind one’s back,

whispers that seem to go through you, like burning.

(moves away from the fence and plucks absent-mindedly at some

leaves)

If only I had something strong to be drinking.

Or could move around unseen in the throng. —

Or could be quite unknown. — Something really strong

to deaden the mockery’s best to my thinking.

(looks round suddenly as though startled; then hides in the

bushes. Some people with wedding presents pass by on

their way to the wedding party)

MAN (in conversation)

His father was a drunkard, his ma a useless crone. 390

A WOMAN It isn’t to be wondered at the lad turned out a drone.

(as they pass, Peer Gynt emerges, shame-faced and stares after them)

PEER (quietly) Was it me they spoke of?

(with a forced shrug) O, let them chatter!

They can’t take my life away, so what matter?

(throws himself down in the heather stretches out on his

back, with hands behind his head and stares up into the air)

What a wonderful cloud. It looks like a horse.

There’s a man astride, — a halter, a saddle. —

Then there’s a broomstick, an old hag astraddle. —

(chuckles to himself)

That’s my Ma. “You swine” she says, yelling of course;

“Hi, you Peer!” —— (his eyes gradually close)

Yes, now she’ll be scared hollow. —

Peer Gynt rides ahead and a crowd of folk follow. —

His horse silver-crested with gold shoes to step on. 400

Gauntlets for him and a scabbard and weapon.

Loose-flowing cape with a fine silk lining,

those in his train all resplendent and shining.

Nobody sits quite so sturdy and upright.

Nobody glitters like him to the sunlight. —

The people are crowding the barriers below,

waving their hats, gazing up at the show.

The women curtsey. Each knows and admires

Emperor Peer Gynt and his thousands of squires.

Florins are scattered and guineas that litter 410

the road just like pebbles till all’s one great glitter.

Wealthy as lords are the folk in these quarters.

Peer Gynt rides on high as he crosses the waters.

England’s prince waits for him there on the shore,

so do the English girls, lasses galore.

England’s great nobles and England’s great king

rise from high table at Peer’s riding in.

The king, he raises his crown and he says —

ASLAK THE SMITH (to some others as they cross behind the fence)

If it isn’t Peer Gynt, the drunken swine — !

PEER (starts) Your Majesty —

ASLAK (leans over the fence and grins)

Wake up lad, rise and shine! 420

PEER What the hell — ! It’s Aslak! What’s it to you?

ASLAK (to the others)

Got the booze in him still from the Lunde do.

PEER (jumps up) Go, while the going’s good.

SMITH Or I might stay.

Where have you sprung from? You’ve been away

six weeks. What’s happened? Pixified, eh?

PEER I’ve done some wonderful things, you know, smith!

ALSLAK (winks to the others)

Tell us, Peer.

PEER Things you’ve no business with.

ASLAK (pause) Are you off to Hægstad?

PEER No.

ASLAK Is it true

time was when the girl there fancied you?

PEER You sooty crow, you — !

ASLAK (backs away) Now, Peer, don’t be sore. 430

If Ingrid’s ditched you, there’s plenty more — ;

just fancy; Jon Gynt’s son! Come with us, do;

there’s lots of young lamb coming, prime widows too —

PEER To hell!

ASLAK One’ll fancy you, heavens above.

Good day, then. I’ll give the bride all your love.

(they go off laughing and whispering)

PEER (looks after them for a moment, shrugs, and half turns away)

For me, that Hægstad girl can swap oaths

with any man she may choose, who cares?

(inspects himself)

Rough and ragged. Breeks full of tears. —

What wouldn’t I give for a change of clothes. (stamps)

If only I had the butcher’s knack — 440

to rip from their breasts the scorn they all share!

(looks round sharply)

Who’s that sniggered behind my back?

Hmm, sounded real — no, nobody there. —

I’ll go home to Ma.

(starts up the hill but stops again and listens to the wedding party)

The dancing’s begun!

(he stands there listening; descends a step at a time; his eyes shine;

he rubs his hands on his thighs)

What a swam of young lassies! Seven, eight girls to one!

I must go down there — but, hell, there’s a catch! —

There’s Ma — still perched on the mill-house thatch! ——

(his eyes are attracted down the hill again; he gives a skip and

laughs)

Heigh, they’re off in the yard now, for dancing

the Halling! Yes, Guttorm’s hot stuff with the bow! *

It sounds and it spouts like a waterfall’s flow. 450

And that glittering bevy of girls is entrancing! —

I’m off to the party — to hell with the catch!

(leaps over the fence and makes off down the road)

_______________

(The farmyard at Hægstad. The farmhouse at the back.

Crowds of guests. Lively dancing on the grass. The FIDDLER sits on a table. The STEWARD stands in the doorway. SERVING WOMEN

move between the buildings. The OLDER FOLK sit around

talking)

WOMAN (joins a group sitting on logs)

The bride? O, she’s bound to cry at the last;

nothing there though, to worry or nag on.

STEWARD (in another group)

Come on, my friends, you must empty the flagon.

MAN Thank you kindly, but you serve us too fast.

LAD (to the fiddler as he dashed past with a girl on his arm)

Go it, Guttorm, don’t spare the stringing!

GIRL Scrape till the meadows sound with their ringing!

GIRLS (in a ring round a boy dancing)

That’s a great jump!

GIRL He’s got legs full of feeling!

LAD It’s wide to the walls here and high to the ceiling! 460

GROOM (approaches his FATHER who is talking with one or two other men, tugs at his sleeve whispering)

She won’t, Dad, she’s proud, she’s too proud by half.

FATHER What won’t she do, then?

GROOM She’s locked in, you see.

FATHER Well, then, why don’t you look for the key?

GROOM I wouldn’t know how to.

FATHER You gormless calf.

(turns back to the others. The Groom drifts across the yard)

LAD (emerging from behind the house)

Lasses, this party here won’t be a slow one!

Peer Gynt’s just turned up!

ASLAK (who has just come in)

Who asked him?

STEWARD No-one.

(goes towards the house)

ASLAK (to the girls)

If he should speak to you, just ignore him.

GIRLS (to each other)

No; we’ll pretend that we never saw him.

PEER (enters excited and eager, stops in front of the group and

rubs his hands)

Who’s the liveliest girl? You must know one.

GIRL 1 (as he approaches)

‘Tisn’t me.

GIRL 2 (likewise)

‘Tisn’t me.

GIRL 3 Nor me — don’t you kid you. 470

PEER (to a fourth)

Come on, before someone turns up to out-bid you.

GIRL 4 (turns away) Haven’t the time.

PEER (to a fifth) You then!

GIRL 5 I’m leaving, alone.

PEER Today? Are you out of your mind? Why that’s mouldy.

ASLAK (a moment later, sotto voce)

There she goes, Peer — to dance with an oldie.

PEER (turns abruptly to an older man)

Where are the spare ones then, mate?

MAN Find your own. (moves away)

(Peer Gynt is suddenly subdued. He glances furtively and shyly at

the gathering. Everyone stares at him but nobody speaks. He approaches various groups. Wherever he goes, silence falls; when he moves on, people smile and follow him with their eyes)

PEER (to himself)

Glances, gimlet-sharp thoughts and the smile.

It grates like a saw-blade under the file!

(he slinks along the fence. SOLVEIG, holding hands with little HELGA, enters the yard following their parents.)

MAN 1 (to another near Peer Gynt)

The folk who’ve just moved here.

MAN 2 The west country lot?

MAN 1 The ones out at Hedale.

MAN 2 Like as not.

PEER (accosts the arrivals, points to Solveig and asks the husband)

May I dance with your daughter?

FATHER (quietly) You may, yes, but first we must go and pay our respects to our neighbours.

(they go in)

STEWARD (offering a drink)

Now you’re here, d’you fancy a drink for your labours?

PEER (staring after them)

Thanks, but I’m dancing. I don’t have a thirst.

(the Steward moves on. Peer looks towards the house and smiles)

How fair! I’ve not seen the like before!

Eyes on her shoes, the white apron she’s wrapped in — !

And she clutched at her mother’s pinafore,

and carried a prayer-book wrapped in a napkin —

I must watch for that girl. (moves to enter the house)

LAD (coming out with the others) Are you leaving the do

already?

PEER No.

LAD Why, then, your steering’s askew!

(takes him by the shoulder to turn him)

PEER Let me pass; move aside!

LAD Scared the blacksmith will get you? 490

PEER Me, scared?

LAD Yes, remember the Lunde great set-to?

(the group moves towards the dancers laughing)

SOLVEIG (in the doorway)

Are you the boy who would like to dance?

PEER I certainly am, can’t you tell at a glance?

(takes her hand)

Come on then!

SOLVEIG Mum says I mustn’t stay.

PEER Mum says? Mum — ? Were you born yesterday?

SOLVEIG Don’t make fun — !

PEER You look young by my reckoning.

You confirmed yet? *

SOLVEIG I went to the priest last spring.

PEER Well, tell us your name, lass, we’ll chat the more brightly.

SOLVEIG My name is Solveig. — And what are you called?

PEER Peer Gynt.

SOLVEIG (takes her hand away) O heavens!

PEER Why so appalled? 500

SOLVEIG My garter’s come loose; I must tie it more tightly.

SOLVEIG My garter’s come loose; I must tie it more tightly.

(leaves him)

GROOM (tugging at his mother)

Mother, she wouldn’t —

MOTHER What wouldn’t she, pray?

GROOM She wouldn’t, Ma!

MOTHER What?

GROOM Undo the locks.

FATHER (under his breath angrily)

O, for two pins you’d be stalled with the ox!

MOTHER Don’t bully the boy. He’s all right in his way.

(they leave)

LAD (who comes away from the dancing with a whole crowd)

Peer, some brandy?

PEER No.

LAD Just a tot?

PEER (looks at him gloomily)

Got it, have you?

LAD I might have come by some.

(pulls out a hip-flask and drinks)

Wow, does it burn! — Well?

PEER Let me try some.

(drinks)

LAD 2 Now you must try the stuff I’ve got.

PEER No!

SAME LAD Come on! Stop whinging now, stop! 510

Drink up, Peer!

PEER Then give us a drop.

(takes another swig)

GIRL (half under her breath)

Time we were off.

PEER You’re afraid of me, no?

PEER You’re afraid of me, no?

LAD 3 Who isn’t afraid of you?

LAD 4 No wonder, after the tricks you got up to at Lunde.

PEER I could do a sight more if I let myself go!

LAD 1 (whispers) Here comes the old Peer!

SEVERAL Let’s hear you say!

Do what then?

PEER Tomorrow — !

OTHERS No, now, today!

GIRL Are you a magician?

PEER Can call up Old Nick!

MAN And so could my granny before I was born.

PEER Liar! There’s no-one can match my trick.

I once lured him into a nut one fine morn.

It was worm-eaten, see?

VOICES (laughing) Yes, that’s nothing surprising!

PEER He cussed and he cried, said he’d pay me, devising

This way and that —

VOICE But he had to stay in?

PEER O yes. I plugged the hole with a pin.

Heigh; should have heard him buzzing and grumbling!

GIRL Just fancy!

PEER Like hearing a bee when it’s bumbling.

GIRL Have you got him still in your nut, then?

PEER O no.

The devil’s out now and on the go.

And it’s his fault the smith always takes me to task. 530

LAD How’s that?

PEER I went to the smithy to ask

would he please break me the shell with his wrench.

He promised; and set it down on his bench;

But Aslak now, has a heavy hand; —

It comes of using the sledge and no wonder —

VOICE Did he smite the fiend?

PEER Like a man, it was grand.

The fiend though was quick, — like a blazing brand

burst through the roof, split the wall asunder.

VOICES And the smith?

PEER He stood there, hands scorched, like a dummy.

Since that day, we haven’t been chummy.

(general laughter)

VOICE That yarn was a peach!

OTHERS The best of them, clearly.

PEER Think I was making it up?

MAN O no.

There you’re not guilty; I got most of it, nearly,

from Granddad —

PEER Lies. It was me, you know!

MAN It is, every time.

PEER (with a toss of his head) Heigh, I can go through

air on magnificent steeds, I can really!

I can do lots of things, I shall show you.

(another roar of laughter)

VOICE Peer, ride on the air for us!

VOICES Yes, come on Peer —

PEER You’re whining and begging’s not needed, you hear?

I shall ride o’er your heads like a raging thunder! 550

The whole parish shall fall at my feet in wonder!

OLDER MAN Now he’s gone stark staring mad.

MAN 2 Agree.

MAN 3 Loudmouth!

MAN 4 You liar!

PEER (threateningly) Just wait, you shall see!

MAN (tipsy)

Yes wait; you’ll end with your coat well lambasted!

VOICES A lovely black eye! Your back proper pasted!

(The crowd disperses, the older ones angry, the younger ones

with laughter and mockery)

GROOM (sidles close)

Hi, Peer, can you ride through the air? Is it true?

PEER (shortly) Anything, Mads! — I’m, believe me, a swell.

GROOM D’you have the invisible cloak with you too? *

PEER Hat, you mean? Yes, I’ve got that as well.

(turns away from him. Solveig crosses the yard holding

Helga’s hand)

PEER (brightens up, goes to meet them)

Solveig! O, but it’s good to be seeing you! 560

(takes Solveig by the wrists)

Now I can twirl with you, light and free!

SOLVEIG Let me go!

PEER Why?

SOLVEIG You’re as wild as can be.

PEER And the reindeer’s wild too when the summer’s due.

Come on, lassie; don’t be so cross!

SOLVEIG (removes her arm)

I daren’t.

PEER Why not?

SOLVEIG (exits with Helga) No, you’ve been drinking.

PEER O if only my knife-blade were sinking

deep into all of them — all that dross!

GROOM (nudging him)

Can’t you find a way I can get to the bride?

PEER (absently)

Bride? And where’s she?

GROOM In the store-house. *

PEER So?

GROOM O please, Peer Gynt, you must have a go! 570

PEER No, you must cope without me at your side.

(a thought strikes him; he says quietly and keenly)

Ingrid in the store-house! (crosses to Solveig)

Decided yet?

(Solveig wants to leave; he stands in her way)

You’re ashamed; I seem like a tramp to you.

SOLVEIG (quickly) O but you’re not; that just isn’t true!

PEER And, what’s more, I’m a drink oversize;

but that was from spite, ‘cos I was upset.

Come on!

SOLVEIG If I wanted to, well — I daren’t!

PEER Who are you afraid of?

SOLVEIG Mostly Dad.

PEER Dad? Of course; the deep sort of parent!

Looks down his nose, does he? — Answer a lad! 580

SOLVEIG What’s there to answer?

PEER Is Daddy your teacher?

Do you and your mother attend his class?

Now will you answer me!

SOLVEIG Please let me pass.

PEER No! (subdued but sharp and threatening)

I can turn into one of the trolls!

I shall come to your bedside as midnight tolls.

If you hear hissing and snarls from some creature,

don’t imagine it’s pussy you hear at its playtime.

It’s me, love! I’ll drain off your blood in a cup;

and as for your sister, I’ll eat her all up;

o yes, I’m a were-wolf once it’s past daytime; — 590

I’ll nibble your loins and your back with my jowl ——

(changes suddenly and entreats her with anguish)

Dance with me, Solveig!

SOLVEIG (looks somberly at him) That was just foul.

(goes in)

GROOM (drifts in again)

You’ll get a steer if you help me!

PEER Come on!

(they go behind the house. At the same time a big group enters from the dancing. Noise and excitement. Solveig, Helga and their parents emerge in the doorway with sundry other older people)

STEWARD (to the Smith, who heads the group)

Keep calm!

ASLAK (takes off his jacket) No, we’ll settle things now, head-on.

It’s Peer Gynt or me that’ll get a banging.

VOICE Yes. Let them fight!

OTHERS No, just a slanging!

ASLAK Fists it must be; just words are no good.

SOLVEIG’S FATHER

Control yourself, man!

HELGA Are they after his blood?

LAD 1 Why not pay him back for all of his lying!

LAD 2 Spit in his eye, then!

LAD 3 Let’s send him flying! 600

LAD 4 (to the Smith)

Seeing it through, then?

ASLAK (throwing down his jacket) Nag must to knacker.

SOLVEIG’S MOTHER

See what they think of that blow-hard, that slacker.

ÅSE (enters with a stick in her hand)

My son, is he here? He’s due for a whack!

O, I’ll wallop him, I shall mangle him!

ASLAK (rolls up his sleeves)

The rod’s much too soft for that rascally back.

MAN 1 Blacksmith’ll mangle him!

MAN 2 Dangle him!

ASLAK (spits on his hand and nods to ÅSE) Strangle him!

ÅSE What, strangle my Peer? You just try it and see!

Fight tooth and claw will old Åse and me! —

Where is he? (calls across the yard)

Peer!

GROOM (runs in) God’s wounds and his passion!

Quick, Ma and Pa and —

FATHER What is it now? 610

GROOM Fancy, Peer Gynt — !

ÅSE (shrieks) Have they killed him some fashion?

GROOM No, Peer Gynt — ! Look, over the brow —

VOICES With Ingrid!

ÅSE (lowers her stick) The monster!

ASLAK (thunderstruck) He’s tackling the sheer

rock-face, by God, and he climbs like a goat!

GROOM (crying)

He’s carrying her, Ma, like a pig you might tote!

ÅSE (shakes her fist at him)

I hope you fall down!

(screams with terror) Watch your footing, d’you hear!

INGRID’S FATHER (enters bareheaded and white with fury)

INGRID’S FATHER (enters bareheaded and white with fury)

His life for this bride-rape — see if I don’t!

ÅSE O no, God punish me, O but you won’t!

Act II[36]

Scene 1

(A narrow path, high up in the mountains. Early morning. Peer Gynt comes hastily and sullenly along the path. Ingrid, still wearing some of her bridal ornaments, is trying to hold him back.)

PEER. Get you from me!

PEER. Get you from me!

INGRID (weeping). After this, Peer? Whither?

PEER. Where you will for me.

INGRID (wringing her hands). Oh, what falsehood!

PEER. Useless railing. Each alone must go his way.

INGRID. Sin—and sin again unites us!

PEER. Devil take all recollections! Devil take the tribe of women—all but one—!

INGRID. Who is that one, pray?

PEER. ’Tis not you.

INGRID. Who is it then?

PEER. Go! Go thither whence you came! Off! To your father!

INGRID. Dearest, sweetest—

PEER. Peace!

INGRID. You cannot mean it, surely, what you’re saying?

PEER. Can and do.