Study notes for the poem “Mandalay”

by

Rudyard Kipling[1]

Contents

Rudyard Kipling’s “Mandalay” – Notes by George Bliar 4

Colonial exploitation of a country’s natural resources 6

Don’t fraternise with the ‘natives’ 9

“Rudyard Kipling” by George Orwell 13

The poem with study notes (in the footnotes) 25

Excerpt from Lycett’s book, “Barrack-Room Ballads | Rudyard Kipling.” 29

Metre, rhythm and musical aspect 35

Musical aspects of Kipling’s poetry 36

The following is an extract from “Kipling and Music” by Brian Mattinson 36

RUDYARD KIPLING description 40

Brief comment on Orwell’s essay about Kipling 41

“Mandalay and Me” by Ray Rasmussen 43

Preliminary note

First of all, I should mention that these notes are written in haste. The Norwegian government although pretending to promote social democratic values had adopted the ‘new public management’ philosophy of Reagan and Thatcher. I won’t delve into this here, but I seem to remember that Thatcher’s parents were grocers. Obviously, grocers have to make a ‘profit’; this ideology was introduced into the public sector. To cut a long story short, I was employed between 1980 and 2020 by the Norwegian state on various short-term contracts over a period of 40 years, despite the fact that Norwegian law made it illegal to employ people on temporary contracts of more than four years. But Norway is not the worst case here. The Conservative British government, despite the Covid-19 crisis, has undermined the health services for many years in the name of ‘austerity and make the rich richer’. But my intention here is not to embark on a political rant but to explain why my lecture notes were often just a regurgitation of information that could be found on various websites; ironically, my ‘original’ contributions were not always appreciated by students as they had various religious and cultural hang ups, and didn’t appreciate a ‘new’ appreciation of old texts.

These ‘draft notes’ were first written in 2011 for a class of students I taught at Telemark University college. The references are incomplete. Moreover, some of the websites I have referred to in 2011 seem to have disappeared in 2022. This reflects the impermanent nature of the Internet. In other words, it is not always easy to trace the sources of the notes some 11 years later.

Rudyard Kipling’s “Mandalay” – Notes by George Bliar[2]

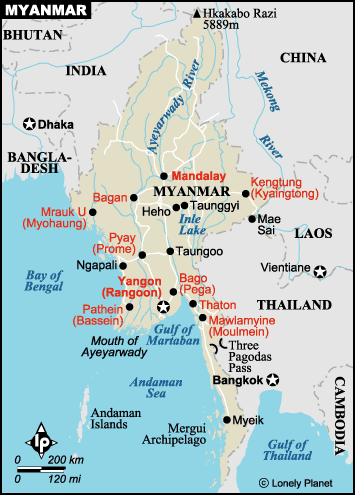

The poem or ballad is about a British soldier of the Empire who tells a story in the first person. He is now in London but looks back on his life abroad, especially a girl he knew, when he was serving as a soldier in Burma (Myanmar).

His life in London is tedious:

I am sick ‘o wastin’ leather on these gritty pavin’-stones,

An’ the blasted English drizzle wakes the fever in my bones;

(verse 5)

He is also fed up with the women he meets in London:

Tho’ I walks with fifty ‘ousemaids outer Chelsea to the Strand,

An’ they talks a lot o’ lovin’, but wot do they understand? ![]() Beefy face an’ grubby ‘and–

Beefy face an’ grubby ‘and– ![]() Law! wot do they understand?

Law! wot do they understand?

(verse 5)

And he misses the girl he knew in Burma:

![]() I’ve a neater, sweeter maiden in a cleaner, greener land!

I’ve a neater, sweeter maiden in a cleaner, greener land! ![]() On the road to Mandalay . . .

On the road to Mandalay . . .

(verse 5)

Part of the attraction of the poem is perhaps because it appeals to the vanity of men, and also to a life free of day-to-day responsibilities. In a faraway land there is a woman …

By the old Moulmein Pagoda, lookin’ lazy at the sea,

There’s a Burma girl a-settin’, and I know she thinks o’ me;

For the wind is in the palm-trees, and the temple-bells they say;

“Come you back, you British Soldier; come you back to Mandalay!”

The narrator is a British soldier; he is at one and the same time a particular soldier or any soldier; he doesn’t even have to be British, but a soldier of any invading army. He is also a specific man, but at the same time any man. This at least is the most likely the intent of the author and the perception of many of the male readers of this popular poem. Some readers will read it at face value – the civilising effect of the British Army and Empire, and the romantic yearnings of a British soldier for a girl in a foreign land. Other readers will interpret the poem as a cheap, jingoist ditty written by a male chauvinist for other male chauvinists. In the following, the narrator will therefore be termed ‘male narrator/reader’.

Unlike the soldier’s wife/girlfriend, the girl only ‘think(s) o’ me’; she doesn’t demand anything of the male narrator/reader, except to be an object of adoration. She is also young and beautiful, and promises an exciting and most likely illicit/forbidden sexuality. Her smoking of cheroots places her in a certain category of women from a Western male viewpoint; the reference to her ‘yellow petticoat’ also reinforces the ‘light pornographic’ aspect (in Victorian terms). The description of the girl is wholly the man’s sexual remembrance of her, and the reason for her existence is to gratify his wishes (within the context of the ballad). Outside of the romantic remembrance of the soldier/man she doesn’t seem to have any life. She is in Victorian terms a light-pornographic image (although perhaps from a 2005 perspective she fits more neatly in a ‘tourist brochure image’).

‘Er petticoat was yaller an’ ‘er little cap was green,

An’ ‘er name was Supi-Yaw-Lat, jes’ the same as Theebaw’s Queen,

An’ I seed her first a-smokin’ of a whackin’ white cheroot,

(verse 2)

Her ‘other life’ outside of the man’s desires is hinted at. She is a Buddhist, but this life is relegated to almost zero in relation to her promiscuous-like relation to the soldier/man. Her ‘cheroot-smokin’ and her desire for the soldier/man’s kisses reflects her ‘real’ erotic/subservient nature, and portrays her religion and perhaps culture as being a mere sham. The word ‘heathen’ is especially interesting in this context. The dictionary definition of the word seems to reveal a history of western cultural arrogance and domination, which was a hallmark of the British Empire.

‘Heathen’ (definition). “a person who does not belong to a widely held religion (especially one who is not a Christian, Jew or Muslim) … an unenlightened person, a person regarded as lacking cultural or moral principles” (New Oxford Dictionary).

It is perhaps implicitly Kipling rather than ‘the soldier’ who shows religious and cultural intolerance in this instance.[3]

An’ wastin’ Christian kisses on an ‘eathen idol’s foot:

Bloomin’ idol made o’ mud–

Wot they called the Great Gawd Budd–

Plucky lot she cared for idols when I kissed ‘er where she stud!

(verse 2)

Her cheroot-smoking suggests that she may be a prostitute, although an explicit romantic image associated with prostitution would be censored from Victorian poetry. Whatever she may be, she seems to evoke the countless women through the ages who for reasons of poverty rather than love gather at places such as harbours “lookin lazily at the sea” for soldiers and sailors to arrive on ships[4]; even when these same soldiers have perhaps been directly, or indirectly, responsible for causing their poverty (as might be said to be the case concerning the British colonialisation of Burma). Ironically, the soldier in the poem is without a name, he is any and every soldier; similarly, the cheroot-smoking girl is any girl/prostitute waiting for a soldier. While soldiers may meet women abroad, fall in love, and marry them, they probably more often have relationships which are of a more pecuniary nature. The participants in such relationships are perhaps not always honest concerning the true nature of their relationships. The author Kipling is at a distance from the narrator of the poem – a distance of social class. The cockney lingo of the soldier signals this. It is not unusual for male sexuality to be expressed in literature and poetry using a ‘distancing effect’ from the author’s own personal life/class, for instance, through the vehicle of a lower social class, or ethnic group.

Her role of fulfilling the soldier’s/man’s desires is continued in the poem when her banjo playing is referred to. Victorian prudery excludes perhaps any images which are too obviously erotic or pornographic. However, her banjo playing and singing, the physical contact between the soldier and girl; the description of her yellow petticoat; and her cheroot smoking are not mere descriptions; they suggest a readiness to enjoy life and its pleasures, far away from the soldier’s dull life in London:

When the mist was on the rice-fields an’ the sun was droppin’ slow,

She’d git ‘er little banjo an’ she’d sing “Kulla-la-lo!”

With ‘er arm upon my shoulder an’ ‘er cheek again my cheek

We useter watch the steamers an’ the hathis pilin’ teak.

Colonial exploitation of a country’s natural resources

The real purpose of the soldier’s presence in Burma, ‘pilin’ teak’, is only mentioned inadvertently in the poem. The following extract from Amitav Ghosh’s “The Glass Palace” comments on the British Empire’s exploitation of Burma’s “valuable natural resources – teak, ivory, petroleum”:

Forgotten and abandoned, the king and queen led a life of increasing shabbiness and obscurity in an unfamiliar territory while their country got depleted of its valuable natural resources – teak, ivory, petroleum. The rapacity and greed inherent in the colonial process is seen concentrated in what happened in Burma, and the author does not gloss over the fact that Indians were willing collaborators in this British enterprise of depredation.[5]

The girl’s ‘young charms’ are emphasised and they contrast with the grey life of the older soldier in London: “An’ I’m learnin’ ‘ere in London what the ten-year soldier tells:” (verse 4)

She understands his needs, whereas the English women don’t, and neither are they pretty:

Tho’ I walks with fifty ‘ousemaids outer Chelsea to the Strand,

An’ they talks a lot o’ lovin’, but wot do they understand?

Beefy face an’ grubby ‘and–

Law! wot do they understand?

The style of a ballad demands perhaps that women are ‘maidens’. This ballad/poem is no exception:

I’ve a neater, sweeter maiden in a cleaner, greener land!

On the road to Mandalay . . .

However, there is an unintended irony here, because it seems unlikely that a young prostitute could also be a virgin.

Traditionally, in literature and poetry, England is often called a ‘green land’:

And did those feet in ancient time

Walk upon England’s mountains green:

And was the holy Lamb of God,

On England’s pleasant pastures seen![6]

The poem implies that England (London) is dirty: “these gritty pavin’-stones.” This was the consequence of 150 years of industrialisation,[7] which also necessitated the invasion of foreign countries (colonies) in order to establish markets and acquire raw material to feed the industrialism.

Mandalay is a cleaner, greener land because the narrator is a soldier who invades and conquers it. He conquers the land and tastes the pleasures the land can offer in the form of the woman, who symbolises the fruits of the land which may be stolen by the invaders. He performs a rape by ‘consent’.

” For the wind is in the palm-trees, and the temple-bells they say;

“Come you back, you British Soldier; come you back to Mandalay!”

These two lines in the first verse seem to refer to the thoughts of the girl, or any girl in an invaded country. In a wider context they refer to the country, although this seems to be the author’s/‘British’ point of view rather than the genuine view of the inhabitants of a country that has been invaded, occupied and colonialized – a rape without consent. The British/Kipling’s/soldier’s viewpoint is then a piece of rationalisation, the mental gymnastics often performed by invading countries when they are clearly morally wrong. In this case the ‘smokescreen’ camouflaging the brutal, violent and immoral invasion of a country is a romantic vision.

Interestingly, in the nineteenth century Britain brought civilisation to the ‘heathens’. In the twentieth and the twentieth-first centuries western countries are ‘democratising’ rather than civilising countries they invade.

The soldier/man is bound by the laws and morals of the society he lives in. The trammels of society might be said to be symbolised by:

Ship me somewheres east of Suez, where the best is like the worst,

Where there ain’t no Ten Commandments an’ a man can raise a thirst;

(verse 6)

In other words, the soldier when abroad feels that he has been freed from the moral Christian straitjacket of his home country. The soldier/man is tired of his duties and responsibilities, and the rewards or lack of rewards they offer, as symbolised by the ‘non-feminine/non-understanding Chelsea housemaids. It is a fairly common occurrence we read in the ‘world news’ everyday of soldiers who invade foreign countries who no longer feel bound and restricted by conventional morality, and who commit violent acts towards women and children. War and invasions seems to erode the laws of society which make us ‘civilised’. The narrator desires to live-out the other half of his ‘self’, which is censored/held in check by society as symbolised by the “Ten Commandments”. He wants to travel somewhere where he will no longer be bound by morality – i.e. amongst the ‘heathens’. His ‘thirst’ refers perhaps to a thirst for life, a ‘sensual and erotic thirst’.

To the modern reader, this conjures up images of the modern tourist sex-trade, which is now widely established in Asia for European ‘tourists’ and soldiers (for instance, the thriving sex-trade in Vietnam during the American invasion of that country). This sex-trade is also especially popular with older men as hinted at in the poem.

These older sex-tourists can get far away ‘east of Suez’ from the women of their own country who may demand some kind of equality in a relationship, expressed in the poem as women with “Beefy face an’ grubby ‘and—” (verse 5); this perhaps indicates the narrator’s chauvinistic view of their femininity as being ‘masculine’, and their grubby hands as symbolising the drudgery of their family and working lives.

The mention of the Suez Canal again inadvertently introduces the ‘beneficial’ effects of Empire. The Suez Canal was the main artery for trade between East and West, and was eventually bought by the British, then ‘lost’ in a colonial war in the 1950s.

Don’t fraternise with the ‘natives’

The undercurrent of the ballad is that the invasion and occupation of the country by the British was something which was welcomed by the Burmese. This resulted in an easy relationship between the governed and the rulers with social intermingling. This couldn’t be further from the truth. The British did not ‘fraternise’ with the ‘natives’ in the East. They ‘imported’ their wives from Britain, and socially mixed with other British colonials in their clubs (see the writings of George Orwell, for instance, Burmese Days). Kipling lets the British soldier ‘fraternise’ with a local girl. This is hypocritical and patronising towards both the British working class soldiers and the inhabitants of the country. The social and moral codes that governed the behaviour of middle and upper class British (officer class) did not apply to the working class British soldiers and the inhabitants of the colonialised country. Thus, the officer class could not publicly fraternise with the women of the invaded country (although they kept mistresses, such as John Flory’s Burmese mistress Ma Hla May in Orwell’s novel, “Burmese Days”.

A description of the principle of non-fraternisation with colonial subjects:

Britain’s colonies around the world spawned generations of European settlers who were born, had married and died there, living a life of luxury enjoyed only by the wealthy in their distant homeland. A comparatively recent addition to the British Empire, Burma was no exception.

A cardinal rule of the Governors of Empire in the early twentieth century was that Europeans should not fraternise with natives of the territory they controlled, but live socially segregated in Cantonment and Club. This was deemed vital to maintain the subtle atmosphere of superiority needed to govern and live in peace with millions of subject peoples with a minimum of effort and cost. Those seen to break this rule had virtually no chance of promotion to a senior job, or if they had one, were banned from the exclusive cantonments where Sahib and Memsahib, surrounded by servants, lived sheltered lives in a little Scotland, Wales or England, before going home in disgrace.

http://www.shareholderpower.com/legacy_links.html[8]

British colonial soldiers and sexually transmitted diseases

That ‘fraternisation’ was more or less forbidden, reinforces the idea that the girl was a prostitute. Also, Kipling was concerned about British soldiers in the colonies who caught sexual transmitted diseases from the prostitutes of the occupied countries. He was not so much concerned about the welfare of the soldiers (or the girls) but the cost to the British – at least this is expressed in the following:

Kipling took up the causes of the rank and file in his journalism. For example, he campaigned for a more realistic approach to sex. The soldiers often used the services of local bazaar prostitutes, but the authorities made little attempt to inspect the girls involved, with the result, Kipling argued, that there were nine thousand “expensive white men a year always laid from venereal disease.” http://www.ereader.com/product/book/excerpt/12833[9]

A more up-to-date source:

Veneral disease and the Lock Hospitals

As Kipling said in his autobiography, “Something Of Myself” :

“it was counted impious that bazaar prostitutes should be inspected or that the men be taught elementary precautions in dealing with them . This official virtue cost our Army in India nine thousand expensive white men a year laid up with venereal disease.”

Venereal disease was one of the most frequent causes of admission to hospital among British troops in India throughout the nineteenth century. Most of the men and approximately two thirds of the officers were unmarried and prostitutes provided “a vitally important form of relaxation”. The military authorities recognised this and so did not forbid access to prostitutes.[10]

The patronising attitude of the author towards the working classes is perhaps most clearly reflected in the attempt to phonetically reproduce the language of the Cockney. This is something which was observed by George Orwell in his essay “Rudyard Kipling” (see below):

This is impossible to Kipling, who is looking down a distorting class-perspective, and by a piece of poetic justice one of his best lines is spoiled — for ‘follow me ’ome’ is much uglier than ‘follow me home’. But even where it makes no difference musically the facetiousness of his stage Cockney dialect is irritating.

Few authors attempted traditionally to reproduce working class speech in writing, and the majority who did were perhaps from the middle classes.

The poem seems to anticipate G.B.Shaw’s Pygmalion. Although, Shaw and Kipling were supposedly from opposing ends of the political spectrum, they both attempted to present what they felt were sympathetic portraits of the working classes. However, their phonetic transcriptions of Cockney language exhibit patronising attitudes, which may be expected of the conservative Kipling, but not of the ‘socialist’, Shaw. There is a common misunderstanding (which is often reflected in British school syllabuses) that standard spoken English has its mirror reflection with standard written English, whereas, regional and ‘social’ dialects do not. It is therefore in a pedantic’/middleclass’/schools’ context not grammatical to say or write “he ain’t not done it”, because it is grammatically incorrect (a double negative, and because ‘ain’t’ should be spoken/written “has /hэz/ not”). Shaw writes the Cockney dialect phonetically, yet makes no attempt to write the middle class dialect phonetically (though why not, as he wanted to introduce a new system of spelling, and was obviously aware of the lack of correspondence between ‘standard written and spoken English’). One of the main humorous elements in Shaw’s play is the mockery of Eliza’s non-standard English of Eliza, which would allow the middle class audiences to patronisingly laugh (although Shaw purports to be a Socialist and intends to participate in the ‘class struggle’, he portrays Cockney speech unsympathetically). Similarly, the soldier in “Mandalay” is different from us and interesting from our patronising point of view because of his speech.

The main element of this Cockney speech is the dropping of aitches (as Orwell notes):

An’ ‘er name

‘eathen

‘er where she stud!

She’d git ‘er little banjo

She’d git ‘er little banjo an’ she’d sing “Kulla-la-lo!”

With ‘er arm upon my shoulder an’ ‘er cheek again my cheek

Where the silence ‘ung that ‘eavy you was ‘arf afraid to speak!

Other comical, patronising transcriptions of Cockney speech are:

‘Wot’ and ‘Gawd’.

This ‘written Cockney’ is reinforced in contrast with the standard written English which appears for a few lines:

For the wind is in the palm-trees, and the temple-bells they say;

“Come you back, you British Soldier; come you back to Mandalay!” ![]() Come you back to Mandalay,

Come you back to Mandalay, ![]() Where the old Flotilla lay;

Where the old Flotilla lay;

It is unclear who is the speaker here of the standard English (the ‘temple-bells’, or a second third person narrator?). However, this will go unnoticed on an ‘ordinary’ reading of the poem, and was perhaps also ‘unnoticed’ by Kipling. The standard English, however, serves to reinforce the different aspect of the Cockney English.

A discussion which has not been entered into here is the recent theories concerning the Theory of the Other of Edward Said. A thorough analysis of the poem would beg the use of this theory. For instance, consider Nandi Bhatia’s article, ‘Kipling’s Burden: Representing Colonial Authority and Constructing the “Other” through Kimball O’Hara and Babu Hurree Chander in Kim’.

“Rudyard Kipling”[11] [12] by George Orwell

It was a pity that Mr. Eliot should be so much on the defensive in the long essay with which he prefaces this selection of Kipling’s poetry, but it was not to be avoided, because before one can even speak about Kipling one has to clear away a legend that has been created by two sets of people who have not read his works. Kipling is in the peculiar position of having been a byword for fifty years. During five literary generations every enlightened person has despised him, and at the end of that time nine-tenths of those enlightened persons are forgotten and Kipling is in some sense still there. Mr. Eliot never satisfactorily explains this fact, because in answering the shallow and familiar charge that Kipling is a ‘Fascist’, he falls into the opposite error of defending him where he is not defensible. It is no use pretending that Kipling’s view of life, as a whole, can be accepted or even forgiven by any civilized person. It is no use claiming, for instance, that when Kipling describes a British soldier beating a ‘nigger’ with a cleaning rod in order to get money out of him, he is acting merely as a reporter and does not necessarily approve what he describes. There is not the slightest sign anywhere in Kipling’s work that he disapproves of that kind of conduct — on the contrary, there is a definite strain of sadism in him, over and above the brutality which a writer of that type has to have. Kipling is a jingo imperialist, he is morally insensitive and aesthetically disgusting. It is better to start by admitting that, and then to try to find out why it is that he survives while the refined people who have sniggered at him seem to wear so badly.

And yet the ‘Fascist’ charge has to be answered, because the first clue to any understanding of Kipling, morally or politically, is the fact that he was not a Fascist. He was further from being one than the most humane or the most ‘progressive’ person is able to be nowadays. An interesting instance of the way in which quotations are parroted to and fro without any attempt to look up their context or discover their meaning is the line from (Kipling’s poem) ‘Recessional’, ‘Lesser breeds without the Law’. This line is always good for a snigger in pansy-left circles. It is assumed as a matter of course that the ‘lesser breeds’ are ‘natives’, and a mental picture is called up of some pukka sahib in a pith helmet kicking a coolie. In its context the sense of the line is almost the exact opposite of this. The phrase ‘lesser breeds’ refers almost certainly to the Germans, and especially the pan-German writers, who are ‘without the Law’ in the sense of being lawless, not in the sense of being powerless. The whole poem, conventionally thought of as an orgy of boasting, is a denunciation of power politics, British as well as German. Two stanzas are worth quoting (I am quoting this as politics, not as poetry):

If, drunk with sight of power, we loose

Wild tongues that have not Thee in awe,

Such boastings as the Gentiles use,

Or lesser breeds without the Law –

Lord God of hosts, be with us yet,

Lest we forget – lest we forget!

For heathen heart that puts her trust

In reeking tube and iron shard,

All valiant dust that builds on dust,

And guarding, calls not Thee to guard,

For frantic boast and foolish word –

Thy mercy on Thy People, Lord!

Much of Kipling’s phraseology is taken from the Bible, and no doubt in the second stanza he had in mind the text from Psalm CXXVII: ‘Except the lord build the house, they labour in vain that build it; except the Lord keep the city, the watchman waketh but in vain.’ It is not a text that makes much impression on the post-Hitler mind. No one, in our time, believes in any sanction greater than military power; no one believes that it is possible to overcome force except by greater force. There is no ‘Law’, there is only power. I am not saying that that is a true belief, merely that it is the belief which all modern men do actually hold. Those who pretend otherwise are either intellectual cowards, or power-worshippers under a thin disguise, or have simply not caught up with the age they are living in. Kipling’s outlook is prefascist. He still believes that pride comes before a fall and that the gods punish hubris. He does not foresee the tank, the bombing plane, the radio and the secret police, or their psychological results.

But in saying this, does not one unsay what I said above about Kipling’s jingoism and brutality? No, one is merely saying that the nineteenth-century imperialist outlook and the modern gangster outlook are two different things. Kipling belongs very definitely to the period 1885-1902. The Great War and its aftermath embittered him, but he shows little sign of having learned anything from any event later than the Boer War. He was the prophet of British Imperialism in its expansionist phase (even more than his poems, his solitary novel, The Light that Failed, gives you the atmosphere of that time) and also the unofficial historian of the British Army, the old mercenary army which began to change its shape in 1914. All his confidence, his bouncing vulgar vitality, sprang out of limitations which no Fascist or near-Fascist shares.

Kipling spent the later part of his life in sulking, and no doubt it was political disappointment rather than literary vanity that account for this. Somehow history had not gone according to plan. After the greatest victory she had ever known, Britain was a lesser world power than before, and Kipling was quite acute enough to see this. The virtue had gone out of the classes he idealized, the young were hedonistic or disaffected, the desire to paint the map red had evaporated. He could not understand what was happening, because he had never had any grasp of the economic forces underlying imperial expansion. It is notable that Kipling does not seem to realize, any more than the average soldier or colonial administrator, that an empire is primarily a money-making concern. Imperialism as he sees it is a sort of forcible evangelizing. You turn a Gatling gun on a mob of unarmed ‘natives’, and then you establish ‘the Law’, which includes roads, railways and a court-house. He could not foresee, therefore, that the same motives which brought the Empire into existence would end by destroying it. It was the same motive, for example, that caused the Malayan jungles to be cleared for rubber estates, and which now causes those estates to be handed over intact to the Japanese. The modern totalitarians know what they are doing, and the nineteenth-century English did not know what they were doing. Both attitudes have their advantages, but Kipling was never able to move forward from one into the other. His outlook, allowing for the fact that after all he was an artist, was that of the salaried bureaucrat who despises the ‘box-wallah’ and often lives a lifetime without realizing that the ‘box-wallah’ calls the tune.

But because he identifies himself with the official class, he does possess one thing which ‘enlightened’ people seldom or never possess, and that is a sense of responsibility. The middle-class Left hate him for this quite as much as for his cruelty and vulgarity. All left-wing parties in the highly industrialized countries are at bottom a sham, because they make it their business to fight against something which they do not really wish to destroy. They have internationalist aims, and at the same time they struggle to keep up a standard of life with which those aims are incompatible. We all live by robbing Asiatic coolies, and those of us who are ‘enlightened’ all maintain that those coolies ought to be set free; but our standard of living, and hence our ‘enlightenment’, demands that the robbery shall continue. A humanitarian is always a hypocrite, and Kipling’s understanding of this is perhaps the central secret of his power to create telling phrases. It would be difficult to hit off the one-eyed pacifism of the English in fewer words than in the phrase, ‘making mock of uniforms that guard you while you sleep’. It is true that Kipling does not understand the economic aspect of the relationship between the highbrow and the blimp. He does not see that the map is painted red chiefly in order that the coolie may be exploited. Instead of the coolie he sees the Indian Civil Servant; but even on that plane his grasp of function, of who protects whom, is very sound. He sees clearly that men can only be highly civilized while other men, inevitably less civilized, are there to guard and feed them.

How far does Kipling really identify himself with the administrators, soldiers and engineers whose praises he sings? Not so completely as is sometimes assumed. He had travelled very widely while he was still a young man, he had grown up with a brilliant mind in mainly philistine surroundings, and some streak in him that may have been partly neurotic led him to prefer the active man to the sensitive man. The nineteenth-century Anglo-Indians, to name the least sympathetic of his idols, were at any rate people who did things. It may be that all that they did was evil, but they changed the face of the earth (it is instructive to look at a map of Asia and compare the railway system of India with that of the surrounding countries), whereas they could have achieved nothing, could not have maintained themselves in power for a single week, if the normal Anglo-Indian outlook had been that of, say, E.M. Forster. Tawdry and shallow though it is, Kipling’s is the only literary picture that we possess of nineteenth-century Anglo-India, and he could only make it because he was just coarse enough to be able to exist and keep his mouth shut in clubs and regimental messes. But he did not greatly resemble the people he admired. I know from several private sources that many of the Anglo-Indians who were Kipling’s contemporaries did not like or approve of him. They said, no doubt truly, that he knew nothing about India, and on the other hand, he was from their point of view too much of a highbrow. While in India he tended to mix with ‘the wrong’ people, and because of his dark complexion he was wrongly suspected of having a streak of Asiatic blood. Much in his development is traceable to his having been born in India and having left school early. With a slightly different background he might have been a good novelist or a superlative writer of music-hall songs. But how true is it that he was a vulgar flagwaver, a sort of publicity agent for Cecil Rhodes? It is true, but it is not true that he was a yes-man or a time-server. After his early days, if then, he never courted public opinion. Mr. Eliot says that what is held against him is that he expressed unpopular views in a popular style. This narrows the issue by assuming that ‘unpopular’ means unpopular with the intelligentsia, but it is a fact that Kipling’s ‘message’ was one that the big public did not want, and, indeed, has never accepted. The mass of the people, in the nineties as now, were anti-militarist, bored by the Empire, and only unconsciously patriotic. Kipling’s official admirers are and were the ‘service’ middle class, the people who read Blackwood’s. In the stupid early years of this century, the blimps, having at last discovered someone who could be called a poet and who was on their side, set Kipling on a pedestal, and some of his more sententious poems, such as ‘If’, were given almost biblical status. But it is doubtful whether the blimps have ever read him with attention, any more than they have read the Bible. Much of what he says they could not possibly approve. Few people who have criticized England from the inside have said bitterer things about her than this gutter patriot. As a rule it is the British working class that he is attacking, but not always. That phrase about ‘the flannelled fools at the wicket and the muddied oafs at the goal’ sticks like an arrow to this day, and it is aimed at the Eton and Harrow match as well as the Cup-Tie Final. Some of the verses he wrote about the Boer War have a curiously modern ring, so far as their subject-matter goes. ‘Stellenbosch’, which must have been written about 1902, sums up what every intelligent infantry officer was saying in 1918, or is saying now, for that matter.

Kipling’s romantic ideas about England and the Empire might not have mattered if he could have held them without having the class-prejudices which at that time went with them. If one examines his best and most representative work, his soldier poems, especially Barrack-Room Ballads, one notices that what more than anything else spoils them is an underlying air of patronage. Kipling idealizes the army officer, especially the junior officer, and that to an idiotic extent, but the private soldier, though lovable and romantic, has to be a comic. He is always made to speak in a sort of stylized Cockney, not very broad but with all the aitches and final ‘g’s’ carefully omitted. Very often the result is as embarrassing as the humorous recitation at a church social. And this accounts for the curious fact that one can often improve Kipling’s poems, make them less facetious and less blatant, by simply going through them and transplanting them from Cockney into standard speech. This is especially true of his refrains, which often have a truly lyrical quality. Two examples will do (one is about a funeral and the other about a wedding):

So it’s knock out your pipes and follow me!

And it’s finish up your swipes and follow me!

Oh, hark to the big drum calling,

Follow me – follow me home!

and again:

Cheer for the Sergeant’s wedding –

Give them one cheer more!

Grey gun-horses in the lando,

And a rogue is married to a whore!

Here I have restored the aitches, etc. Kipling ought to have known better. He ought to have seen that the two closing lines of the first of these stanzas are very beautiful lines, and that ought to have overriden his impulse to make fun of a working-man’s accent. In the ancient ballads the lord and the peasant speak the same language. This is impossible to Kipling, who is looking down a distorting class-perspective, and by a piece of poetic justice one of his best lines is spoiled — for ‘follow me ’ome’ is much uglier than ‘follow me home’. But even where it makes no difference musically the facetiousness of his stage Cockney dialect is irritating. However, he is more often quoted aloud than read on the printed page, and most people instinctively make the necessary alterations when they quote him.

Can one imagine any private soldier, in the nineties or now, reading Barrack-Room Ballads and feeling that here was a writer who spoke for him? It is very hard to do so. Any soldier capable of reading a book of verse would notice at once that Kipling is almost unconscious of the class war that goes on in an army as much as elsewhere. It is not only that he thinks the soldier comic, but that he thinks him patriotic, feudal, a ready admirer of his officers and proud to be a soldier of the Queen. Of course that is partly true, or battles could not be fought, but ‘What have I done for thee, England, my England?’ is essentially a middle-class query. Almost any working man would follow it up immediately with ‘What has England done for me?’ In so far as Kipling grasps this, he simply sets it down to ‘the intense selfishness of the lower classes’ (his own phrase). When he is writing not of British but of ‘loyal’ Indians he carries the ‘Salaam, sahib’ motif to sometimes disgusting lengths. Yet it remains true that he has far more interest in the common soldier, far more anxiety that he shall get a fair deal, than most of the ‘liberals’ of his day or our own. He sees that the soldier is neglected, meanly underpaid and hypocritically despised by the people whose incomes he safeguards. ‘I came to realize’, he says in his posthumous memoirs, ‘the bare horrors of the private’s life, and the unnecessary torments he endured’. He is accused of glorifying war, and perhaps he does so, but not in the usual manner, by pretending that war is a sort of football match. Like most people capable of writing battle poetry, Kipling had never been in battle, but his vision of war is realistic. He knows that bullets hurt, that under fire everyone is terrified, that the ordinary soldier never knows what the war is about or what is happening except in his own corner of the battlefield, and that British troops, like other troops, frequently run away:

I ’eard the knives be’ind me, but I dursn’t face my man,

Nor I don’t know where I went to, ’cause I didn’t stop to see,

Till I ’eard a beggar squealin’ out for quarter as ’e ran,

An’ I thought I knew the voice an’ – it was me![13]

Modernize the style of this, and it might have come out of one of the debunking war books of the nineteen-twenties. Or again:

An’ now the hugly bullets come peckin’ through the dust,

An’ no one wants to face ’em, but every beggar must;

So, like a man in irons, which isn’t glad to go,

They moves ’em off by companies uncommon stiff an’ slow.[14]

Compare this with:

Forward the Light Brigade!

Was there a man dismayed?

No! though the soldier knew

Someone had blundered.[15]

If anything, Kipling overdoes the horrors, for the wars of his youth were hardly wars at all by our standards. Perhaps that is due to the neurotic strain in him, the hunger for cruelty. But at least he knows that men ordered to attack impossible objectives are dismayed, and also that fourpence a day is not a generous pension.

How complete or truthful a picture has Kipling left us of the long-service, mercenary army of the late nineteenth century? One must say of this, as of what Kipling wrote about nineteenth-century Anglo-India, that it is not only the best but almost the only literary picture we have. He has put on record an immense amount of stuff that one could otherwise only gather from verbal tradition or from unreadable regimental histories. Perhaps his picture of army life seems fuller and more accurate than it is because any middle-class English person is likely to know enough to fill up the gaps. At any rate, reading the essay on Kipling that Mr. Edmund Wilson has just published or is just about to publish, I was struck by the number of things that are boringly familiar to us and seem to be barely intelligible to an American. But from the body of Kipling’s early work there does seem to emerge a vivid and not seriously misleading picture of the old pre-machine-gun army — the sweltering barracks in Gibraltar or Lucknow, the red coats, the pipeclayed belts and the pillbox hats, the beer, the fights, the floggings, hangings and crucifixions, the bugle-calls, the smell of oats and horsepiss, the bellowing sergeants with foot-long moustaches, the bloody skirmishes, invariably mismanaged, the crowded troopships, the cholera-stricken camps, the ‘native’ concubines, the ultimate death in the workhouse. It is a crude, vulgar picture, in which a patriotic music-hall turn seems to have got mixed up with one of Zola’s gorier passages, but from it future generations will be able to gather some idea of what a long-term volunteer army was like. On about the same level they will be able to learn something of British India in the days when motor-cars and refrigerators were unheard of. It is an error to imagine that we might have had better books on these subjects if, for example, George Moore, or Gissing, or Thomas Hardy, had had Kipling’s opportunities. That is the kind of accident that cannot happen. It was not possible that nineteenth-century England should produce a book like War and Peace, or like Tolstoy’s minor stories of army life, such as Sebastopol or The Cossacks, not because the talent was necessarily lacking but because no one with sufficient sensitiveness to write such books would ever have made the appropriate contacts. Tolstoy lived in a great military empire in which it seemed natural for almost any young man of family to spend a few years in the army, whereas the British Empire was and still is demilitarized to a degree which continental observers find almost incredible. Civilized men do not readily move away from the centres of civilization, and in most languages there is a great dearth of what one might call colonial literature. It took a very improbable combination of circumstances to produce Kipling’s gaudy tableau, in which Private Ortheris and Mrs. Hauksbee pose against a background of palm trees to the sound of temple bells, and one necessary circumstance was that Kipling himself was only half civilized.

Kipling is the only English writer of our time who has added phrases to the language. The phrases and neologisms which we take over and use without remembering their origin do not always come from writers we admire. It is strange, for instance, to hear the Nazi broadcasters referring to the Russian soldiers as ‘robots’, thus unconsciously borrowing a word from a Czech democrat whom they would have killed if they could have laid hands on him. Here are half a dozen phrases coined by Kipling which one sees quoted in leaderettes in the gutter press or overhears in saloon bars from people who have barely heard his name. It will be seen that they all have a certain characteristic in common:

East is East, and West is West.

The white man’s burden.

What do they know of England who only England know?

The female of the species is more deadly than the male.

Somewhere East of Suez.

Paying the Dane-geld.

There are various others, including some that have outlived their context by many years. The phrase ‘killing Kruger with your mouth’, for instance, was current till very recently. It is also possible that it was Kipling who first let loose the use of the word ‘Huns’ for Germans; at any rate he began using it as soon as the guns opened fire in 1914. But what the phrases I have listed above have in common is that they are all of them phrases which one utters semi-derisively (as it might be ‘For I’m to be Queen o’ the May, mother, I’m to be Queen o’ the May’), but which one is bound to make use of sooner or later. Nothing could exceed the contempt of the New Statesman, for instance, for Kipling, but how many times during the Munich period did the New Statesman find itself quoting that phrase about paying the Dane-geld? The fact is that Kipling, apart from his snack-bar wisdom and his gift for packing much cheap picturesqueness into a few words (’palm and pine’ — ‘east of Suez’ — ‘the road to Mandalay’), is generally talking about things that are of urgent interest. It does not matter, from this point of view, that thinking and decent people generally find themselves on the other side of the fence from him. ‘White man’s burden’ instantly conjures up a real problem, even if one feels that it ought to be altered to ‘black man’s burden’. One may disagree to the middle of one’s bones with the political attitude implied in ‘The Islanders’, but one cannot say that it is a frivolous attitude. Kipling deals in thoughts which are both vulgar and permanent. This raises the question of his special status as a poet, or verse-writer.

Mr. Eliot describes Kipling’s metrical work as ‘verse’ and not ‘poetry’, but adds that it is ‘great verse’, and further qualifies this by saying that a writer can only be described as a ‘great verse-writer’ if there is some of his work ‘of which we cannot say whether it is verse or poetry’. Apparently Kipling was a versifier who occasionally wrote poems, in which case it was a pity that Mr. Eliot did not specify these poems by name. The trouble is that whenever an aesthetic judgement on Kipling’s work seems to be called for, Mr. Eliot is too much on the defensive to be able to speak plainly. What he does not say, and what I think one ought to start by saying in any discussion of Kipling, is that most of Kipling’s verse is so horribly vulgar that it gives one the same sensation as one gets from watching a third-rate music-hall performer recite ‘The Pigtail of Wu Fang Fu’ with the purple limelight on his face, and yet there is much of it that is capable of giving pleasure to people who know what poetry means. At his worst, and also his most vital, in poems like ‘Gunga Din’ or ‘Danny Deever’, Kipling is almost a shameful pleasure, like the taste for cheap sweets that some people secretly carry into middle life. But even with his best passages one has the same sense of being seduced by something spurious, and yet unquestionably seduced. Unless one is merely a snob and a liar it is impossible to say that no one who cares for poetry could get any pleasure out of such lines as:

For the wind is in the palm trees, and the temple bells they say,

‘Come you back, you British soldier, come you back to Mandalay!’

And yet those lines are not poetry in the same sense as ‘Felix Randal’ or ‘When icicles hang by the wall’ are poetry. One can, perhaps, place Kipling more satisfactorily than by juggling with the words ‘verse’ and ‘poetry’, if one describes him simply as a good bad poet. He is as a poet what Harriet Beecher Stowe was as a novelist. And the mere existence of work of this kind, which is perceived by generation after generation to be vulgar and yet goes on being read, tells one something about the age we live in.

There is a great deal of good bad poetry in English, all of it, I should say, subsequent to 1790. Examples of good bad poems — I am deliberately choosing diverse ones — are ‘The Bridge of Sighs’, ‘When all the world is young, lad’, ‘The Charge of the Light Brigade’, Bret Harte’s ‘Dickens in Camp’, ‘The Burial of Sir John Moore’, ‘Jenny Kissed Me’, ‘Keith of Ravelston’, ‘Casabianca’. All of these reek of sentimentality, and yet — not these particular poems, perhaps, but poems of this kind, are capable of giving true pleasure to people who can see clearly what is wrong with them. One could fill a fair-sized anthology with good bad poems, if it were not for the significant fact that good bad poetry is usually too well known to be worth reprinting.

It is no use pretending that in an age like our own, ‘good’ poetry can have any genuine popularity. It is, and must be, the cult of a very few people, the least tolerated of the arts. Perhaps that statement needs a certain amount of qualification. True poetry can sometimes be acceptable to the mass of the people when it disguises itself as something else. One can see an example of this in the folk-poetry that England still possesses, certain nursery rhymes and mnemonic rhymes, for instance, and the songs that soldiers make up, including the words that go to some of the bugle-calls. But in general ours is a civilization in which the very word ‘poetry’ evokes a hostile snigger or, at best, the sort of frozen disgust that most people feel when they hear the word ‘God’. If you are good at playing the concertina you could probably go into the nearest public bar and get yourself an appreciative audience within five minutes. But what would be the attitude of that same audience if you suggested reading them Shakespeare’s sonnets, for instance? Good bad poetry, however, can get across to the most unpromising audiences if the right atmosphere has been worked up beforehand. Some months back Churchill produced a great effect by quoting Clough’s ‘Endeavour’ in one of his broadcast speeches. I listened to this speech among people who could certainly not be accused of caring for poetry, and I am convinced that the lapse into verse impressed them and did not embarrass them. But not even Churchill could have got away with it if he had quoted anything much better than this.

In so far as a writer of verse can be popular, Kipling has been and probably still is popular. In his own lifetime some of his poems travelled far beyond the bounds of the reading public, beyond the world of school prize-days, Boy Scout singsongs, limp-leather editions, pokerwork and calendars, and out into the yet vaster world of the music halls. Nevertheless, Mr. Eliot thinks it worthwhile to edit him, thus confessing to a taste which others share but are not always honest enough to mention. The fact that such a thing as good bad poetry can exist is a sign of the emotional overlap between the intellectual and the ordinary man. The intellectual is different from the ordinary man, but only in certain sections of his personality, and even then not all the time. But what is the peculiarity of a good bad poem? A good bad poem is a graceful monument to the obvious. It records in memorable form — for verse is a mnemonic device, among other things — some emotion which very nearly every human being can share. The merit of a poem like ‘When all the world is young, lad’ is that, however sentimental it may be, its sentiment is ‘true’ sentiment in the sense that you are bound to find yourself thinking the thought it expresses sooner or later; and then, if you happen to know the poem, it will come back into your mind and seem better than it did before. Such poems are a kind of rhyming proverb, and it is a fact that definitely popular poetry is usually gnomic or sententious. One example from Kipling will do:

White hands cling to the bridle rein,

Slipping the spur from the booted heel;

Tenderest voices cry ‘Turn again!’

Red lips tarnish the scabbarded steel:

Down to Gehenna or up to the Throne,

He travels the fastest who travels alone.[16]

There is a vulgar thought vigorously expressed. It may not be true, but at any rate it is a thought that everyone thinks. Sooner or later you will have occasion to feel that he travels the fastest who travels alone, and there the thought is, ready-made and, as it were, waiting for you. So the chances are that, having once heard this line, you will remember it.

One reason for Kipling’s power as a good bad poet I have already suggested — his sense of responsibility, which made it possible for him to have a world-view, even though it happened to be a false one. Although he had no direct connexion with any political party, Kipling was a Conservative, a thing that does not exist nowadays. Those who now call themselves Conservatives are either Liberals, Fascists or the accomplices of Fascists. He identified himself with the ruling power and not with the opposition. In a gifted writer this seems to us strange and even disgusting, but it did have the advantage of giving Kipling a certain grip on reality. The ruling power is always faced with the question, ‘In such and such circumstances, what would you do?’, whereas the opposition is not obliged to take responsibility or make any real decisions. Where it is a permanent and pensioned opposition, as in England, the quality of its thought deteriorates accordingly. Moreover, anyone who starts out with a pessimistic, reactionary view of life tends to be justified by events, for Utopia never arrives and ‘the gods of the copybook headings’, as Kipling himself put it, always return. Kipling sold out to the British governing class, not financially but emotionally. This warped his political judgement, for the British ruling class were not what he imagined, and it led him into abysses of folly and snobbery, but he gained a corresponding advantage from having at least tried to imagine what action and responsibility are like. It is a great thing in his favour that he is not witty, not ‘daring’, has no wish to épater les bourgeois. He dealt largely in platitudes, and since we live in a world of platitudes, much of what he said sticks. Even his worst follies seem less shallow and less irritating than the ‘enlightened’ utterances of the same period, such as Wilde’s epigrams or the collection of cracker-mottoes at the end of Man and Superman.

1942“Mandalay” – the poem

by Rudyard Kipling

1. By the old Moulmein Pagoda, lookin’ lazy at the sea,

There’s a Burma girl a-settin’, and I know she thinks o’ me;

For the wind is in the palm-trees, and the temple-bells they say;

“Come you back, you British Soldier; come you back to Mandalay!” ![]() Come you back to Mandalay,

Come you back to Mandalay, ![]() Where the old Flotilla lay;

Where the old Flotilla lay; ![]() Can’t you ‘ear their paddles clunkin’ from Rangoon to Mandalay?

Can’t you ‘ear their paddles clunkin’ from Rangoon to Mandalay? ![]() On the road to Mandalay,

On the road to Mandalay, ![]() Where the flyin’-fishes play,

Where the flyin’-fishes play, ![]() An’ the dawn comes up like thunder outer China ‘crost the Bay!

An’ the dawn comes up like thunder outer China ‘crost the Bay!

2. ‘Er petticoat was yaller an’ ‘er little cap was green,

An’ ‘er name was Supi-Yaw-Lat jes’ the same as Theebaw’s Queen,

An’ I seed her first a-smokin’ of a whackin’ white cheroot,

An’ wastin’ Christian kisses on an ‘eathen idol’s foot: ![]() Bloomin’ idol made o’ mud–

Bloomin’ idol made o’ mud– ![]() Wot they called the Great Gawd Budd–

Wot they called the Great Gawd Budd– ![]() Plucky lot she cared for idols when I kissed ‘er where she stud!

Plucky lot she cared for idols when I kissed ‘er where she stud! ![]() On the road to Mandalay …

On the road to Mandalay …

3. When the mist was on the rice-fields an’ the sun was droppin’ slow,

She’d git ‘er little banjo an’ she’d sing “Kulla-la-lo!”

With ‘er arm upon my shoulder an’ ‘er cheek again my cheek

We useter watch the steamers an’ the hathis pilin’ teak. ![]() Elephants a-piling teak

Elephants a-piling teak ![]() In the sludgy, squdgy creek,

In the sludgy, squdgy creek, ![]() Where the silence ‘ung that ‘eavy you was ‘arf afraid to speak!

Where the silence ‘ung that ‘eavy you was ‘arf afraid to speak! ![]() On the road to Mandalay …

On the road to Mandalay …

4. But that’s all shove be’ind me — long ago and fur away,

An’ there ain’t no ‘buses runnin’ from the Bank to Mandalay;

An’ I’m learnin’ ‘ere in London what the ten-year soldier tells:

“If you’ve ‘eard the East a-callin’, you won’t never ‘eed naught else.” ![]() No! you won’t ‘eed nothin’ else

No! you won’t ‘eed nothin’ else ![]() But them spicy garlic smells,

But them spicy garlic smells, ![]() An’ the sunshine an’ the palm-trees an’ the tinkly temple-bells;

An’ the sunshine an’ the palm-trees an’ the tinkly temple-bells; ![]() On the road to Mandalay …

On the road to Mandalay …

5. I am sick ‘o wastin’ leather on these gritty pavin’-stones,

An’ the blasted English drizzle wakes the fever in my bones;

Tho’ I walks with fifty ‘ousemaids outer Chelsea to the Strand,

An’ they talks a lot o’ lovin’, but wot do they understand? ![]() Beefy face an’ grubby ‘and–

Beefy face an’ grubby ‘and– ![]() Law! wot do they understand?

Law! wot do they understand? ![]() I’ve a neater, sweeter maiden in a cleaner, greener land!

I’ve a neater, sweeter maiden in a cleaner, greener land! ![]() On the road to Mandalay . . .

On the road to Mandalay . . .

6. Ship me somewheres east of Suez, where the best is like the worst,

Where there ain’t no Ten Commandments an’ a man can raise a thirst;

For the temple-bells are callin’, and it’s there that I would be–

By the old Moulmein Pagoda, looking lazy at the sea; ![]() On the road to Mandalay,

On the road to Mandalay, ![]() Where the old Flotilla lay,

Where the old Flotilla lay, ![]() With our sick beneath the awnings when we went to Mandalay!

With our sick beneath the awnings when we went to Mandalay! ![]() O the road to Mandalay,

O the road to Mandalay, ![]() Where the flyin’-fishes play,

Where the flyin’-fishes play, ![]() An’ the dawn comes up like thunder outer China ‘crost the Bay!

An’ the dawn comes up like thunder outer China ‘crost the Bay!

The poem with study notes (in the footnotes)

By the old Moulmein[19] Pagoda[20], lookin’ lazy at the sea,

By the old Moulmein[19] Pagoda[20], lookin’ lazy at the sea,

There’s a Burma girl a-settin’, and I know she thinks o’ me[21];

For the wind is in the palm-trees, and the temple-bells they say;

“Come you back, you British Soldier[22]; come you back to Mandalay!” ![]() Come you back to Mandalay,

Come you back to Mandalay, ![]() Where the old Flotilla lay;

Where the old Flotilla lay; ![]() Can’t you ‘ear their paddles clunkin’ from Rangoon to Mandalay?

Can’t you ‘ear their paddles clunkin’ from Rangoon to Mandalay? ![]() On the road to Mandalay,

On the road to Mandalay, ![]() Where the flyin’-fishes play,

Where the flyin’-fishes play, ![]() An’ the dawn comes up like thunder outer China ‘crost the Bay!

An’ the dawn comes up like thunder outer China ‘crost the Bay!

‘Er petticoat was yaller [23]an’ ‘er little cap was green,

‘Er petticoat was yaller [23]an’ ‘er little cap was green,

An’ ‘er name was Supi-Yaw-Lat[24] jes’ the same as Theebaw’s Queen[25],

An’ I seed her first a-smokin’ of a whackin’ white cheroot[26],

An’ wastin’ Christian kisses on an ‘eathen idol’s foot: ![]() Bloomin’ idol made o’ mud—

Bloomin’ idol made o’ mud—

![]() Wot they called the Great Gawd Budd[27]—

Wot they called the Great Gawd Budd[27]— ![]() Plucky lot she cared for idols when I kissed ‘er where she stud!

Plucky lot she cared for idols when I kissed ‘er where she stud! ![]() On the road to Mandalay …

On the road to Mandalay …

When the mist was on the rice-fields an’ the sun was droppin’ slow,

She’d git ‘er little banjo an’ she’d sing “Kulla-la-lo!”

With ‘er arm upon my shoulder an’ ‘er cheek again my cheek[28]

We useter watch the steamers an’ the hathis[29] pilin’ teak. ![]() Elephants a-piling teak[30]

Elephants a-piling teak[30] ![]() In the sludgy, squdgy creek,

In the sludgy, squdgy creek, ![]() Where the silence ‘ung that ‘eavy you was ‘arf afraid to speak!

Where the silence ‘ung that ‘eavy you was ‘arf afraid to speak! ![]() On the road to Mandalay …

On the road to Mandalay …

But that’s all shove be’i nd me — long ago and fur away,

But that’s all shove be’i nd me — long ago and fur away,

An’ there ain’t no ‘buses runnin’ from the Bank[31] to Mandalay;

An’ I’m learnin’ ‘ere in London what the ten-year soldier tells:

“If you’ve ‘eard the East a-callin’, you won’t never ‘eed naught else.” ![]() No! you won’t ‘eed nothin’ else

No! you won’t ‘eed nothin’ else ![]() But them spicy garlic smells,

But them spicy garlic smells, ![]() An’ the sunshine an’ the palm-trees an’ the tinkly temple-bells;

An’ the sunshine an’ the palm-trees an’ the tinkly temple-bells; ![]() On the road to Mandalay …

On the road to Mandalay …

I am sick ‘o wastin’ leather on these gritty pavin’-stones,

An’ the blasted English drizzle wakes the fever in my bones;

Tho’ I walks with fifty ‘ousemaids outer Chelsea to the Strand,

An’ they talks a lot o’ lovin’, but wot do they understand? ![]() Beefy face an’ grubby ‘and–

Beefy face an’ grubby ‘and– ![]() Law! wot do they understand?

Law! wot do they understand? ![]() I’ve a neater, sweeter maiden in a cleaner, greener land!

I’ve a neater, sweeter maiden in a cleaner, greener land! ![]() On the road to Mandalay . . .

On the road to Mandalay . . .

Ship me somewheres east of Suez[32], where the best is like the worst,

Where there ain’t no Ten Commandments an’ a man can raise a thirst;

For the temple-bells are callin’, and it’s there that I would be–

By the old Moulmein Pagoda, looking lazy at the sea; ![]() On the road to Mandalay,

On the road to Mandalay, ![]() Where the old Flotilla lay,

Where the old Flotilla lay, ![]() With our sick[33] beneath the awnings when we went to Mandalay!

With our sick[33] beneath the awnings when we went to Mandalay! ![]() O the road to Mandalay,

O the road to Mandalay, ![]() Where the flyin’-fishes play,

Where the flyin’-fishes play, ![]() An’ the dawn comes up like thunder outer China ‘crost the Bay!

An’ the dawn comes up like thunder outer China ‘crost the Bay!

History of the poem

Introduction

“Mandalay” is one of Kipling’s “Barrack-Room Ballads”. The follow excerpt, from Andrew Lycett, provides background information about Kipling’s life, and his writing of the “Barrack-Room Ballads”, amongst other things. [34]

Excerpt from Lycett’s book, “Barrack-Room Ballads | Rudyard Kipling.”

From the Peloponnesian War to the Gulf War, music and songs have been essential features of a soldier’s world. Bugle calls, regimental marches, hymns, bawdy limericks and plaintive laments: whether in the heat of battle or the hierarchical world of the barracks, these provide simple, direct means of communication to maintain discipline, boost morale or simply let off steam — in fact, to cope with all the stresses and strains of army life.

The British writer Rudyard Kipling recognized the powerful effect of song and incorporated its emotion, rhythm and sense of camaraderie into his Barrack-Room Ballads, the series of poems he wrote in the 1890s about the experience of military service in India and other parts of the British Empire.

Kipling was a complicated, brilliant man who wrote many things well — not just poems, but stories, novels and journalism. Not for nothing was he awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1907. He was born in Bombay (now Mumbai) in December 1865, the son of a teacher at the local art college and a spirited Irish-Scottish woman who was related to the well-known Pre-Raphaelite painter Edward Burne-Jones.

At the age of five, Kipling was sent back to England to live with foster parents (an experience he loathed) and later to attend the United Services College, a school for officers who fought in often forgotten campaigns in all corners of the Empire.

Since young Kipling’s aptitude was for literature rather than for battle, he returned to India at the age of sixteen and joined the staff of the daily newspaper, the Civil and Military Gazette in Lahore, the Punjab town where his parents had moved, after his father, Lockwood, was appointed keeper of the local museum.

Kipling slowly readjusted to living in colonial India. Initially he stuck to journalism, demonstrating his sharp eye for color and detail in his reports on corruption in municipal politics in Lahore or the decadence of princely courts. As he traveled more widely, he began to satirize the manipulativeness, self-interest and crass stupidity of his fellow “Anglo-Indians” in a series of poems he called Departmental Ditties and in his stories known as Plain Tales from the Hills.

At the same time, he grew to understand the nature of Empire. Despite his general cynicism, he came genuinely to admire the self-sacrifice of doctors, engineers and other administrators who devoted their lives to bringing sanitation, roads and other benefits of Western civilization to remote areas of India. He convinced himself this was a noble cause. As was clear throughout his life, the doers of Empire became his heroes.

Another body was also essential to getting things done in imperial India: the military. Five miles east of Lahore stood the Mian Mir military cantonment, where an infantry battalion and artillery battery were always stationed. Kipling frequently rode over to Mian Mir, where he made it his business to meet not only the officers in their messes but also the enlisted men in their dusty quarters.

Greatly admiring the humor and fortitude of the ordinary soldier in often appalling conditions, he embarked on a series of stories about their life in India. These tales, as collected in Soldiers Three, featured a trio of enlisted men: the Irishman Terence Mulvaney, the Cockney Stanley Ortheris and the Yorkshire-born Jock Learoyd. No one had previously given fictional voice in this way to lowly privates such as Mulvaney, who in “With the Main Guard” asks, “Mary, Mother av Mercy, fwat the divil possist us to take an’ kape this melancholious counthry? Answer me that, sorr.”

Kipling took up the causes of the rank and file in his journalism. For example, he campaigned for a more realistic approach to sex. The soldiers often used the services of local bazaar prostitutes, but the authorities made little attempt to inspect the girls involved, with the result, Kipling argued, that there were nine thousand “expensive white men a year always laid from venereal disease.” http://www.ereader.com/product/book/excerpt/12833

Kipling’s stories appeared in six volumes of the Indian Railway Library, published by A. H. Wheeler & Co. with covers drawn by his father. Today the dialect of these soldier tales is sometimes difficult to understand. But in the late 1880s, they proved sensational. English literature was experiencing a creative lull after the vibrancy of Dickens and Thackeray. Kipling’s stories provided color and energy, while introducing British readers to a hitherto unknown aspect of the expanding Empire.

One of the six volumes, Soldiers Three, was reviewed in the Spectator in London in March 1889 — unusual for a book published in India. It was also well received by Sidney Low, editor of the conservative daily newspaper the St. James’s Gazette, who pronounced enthusiastically about a new talent “who had dawned upon the eastern horizon. . . . It may be that a greater than Dickens is here.” The generally positive response encouraged Kipling to give up his newspaper job and move to London to try his hand in a much more sophisticated and potentially lucrative market.

Arriving in the British capital in October 1889, Kipling immediately worried that he had made the wrong decision. Out of place among the fashionable aesthetes of the time, he wrote his well-observed poem “In Partibus,” which for some reason he declined to include in his Collected Verse. This chronicled his longing for the sunshine and moral certainties of India, where the Indian army man was

Set up, and trimmed and taut,

Who does not spout hashed libraries

Or think the next man’s thought,

And walks as though he owned himself,

And hogs his bristles short.

After a period of debilitating homesickness, Kipling found his professional feet, especially after meeting W. E. Henley, editor of the influential Conservative journal the Scots Observer. Henley, with his wooden leg, was the model for Long John Silver in his friend Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, published in 1883. He had been alerted to Kipling’s talents by a seafaring brother who had read one of the young man’s poems in an Indian newspaper. He invited Kipling to his club, the Savile, after which his guest pronounced Henley “more different varieties of man than most” — a typically wry compliment.

Kipling agreed to work on a freelance basis for the Scots Observer. This was not too painful: on the surface, it was one of the periodicals most sympathetic to his views. Run by a group of old-fashioned Tories in Edinburgh, it was a forceful proponent of British imperialism.

His first submission was a trifle — a wry Jacobean-style meditation on love and death. However, his second piece was “Danny Deever,” a simple, graphic, rhythmic, insistent ballad about a soldier hanged by his regiment for shooting a colleague. When he read it, Henley is said to have danced on his wooden leg. Published in the Scots Observer on 22 February 1890, it was immediately seized on by David Masson, the opinion-making professor of rhetoric and English literature at Edinburgh University, who exclaimed enthusiastically to his students, “Here’s literature! Here’s literature at last!”

Kipling responded by offering Henley twelve more poems about the travails of military life, which the Scots Observer published over the next few months. Kipling had conceived this kind of verse while in India: in late 1888 he had offered a Calcutta publisher a volume composed of “my Barrack-Room Ballads and other Poems which includes 2 soldiers songs and a variety of Anglo-Indian sentimental and descriptive work,” and on his journey home eastward across the Pacific Ocean and the American continent, he had hummed what he called his “Tommy Atkins ballads” to Edmonia Hill, a well-read American woman whom he had befriended in Allahabad.

However the Barrack-Room Ballads took real poetic form only in the particular circumstances of his life in London. As soon as he arrived, he rented a set of rooms in Villiers Street, running beside Charing Cross Station in the center of town. At the end of his street stood Gatti’s, a popular music hall. Often he would go there after a day’s work, four pence buying admission and a pewter jar of beer. At Gatti’s he got to know something missing in India — the vibrancy of working-class culture. Inspired by the “compelling songs” of the Lion and Mammoth Comiques, he wrote to Edmonia (known as Ted) Hill, saying that London needed “a poet of the Music Halls.” For his old paper, the Civil and Military Gazette in Lahore, he wrote a story, “My Great and Only,” about a venue such as Gatti’s, where, to the uninhibited accompaniment of his audience, a star belts out a ditty about a Life Guard’s inexpert wooing of an undercook. Kipling composed the song himself, complete with the refrain

And that’s what the Girl told the Soldier,

Soldier! Soldier!

An’ that’s what the Girl told the Soldier.

Such entertainments suggested to Kipling that he could bring together the immediacy of the music hall with his firsthand observations of military life (mainly gained in India). This did not mean he wanted to write music hall songs; rather, he intended to draw on popular culture for his soldier poems. And that required him to incorporate elements from the ballads, marches and laments that soldiers had written and sung through the ages, giving them a modern twist.

A ballad essentially tells a story graphically and in verse. It is rhythmic and memorable because it is hewn in the oral tradition. Over the years poets from Wordsworth to Longfellow had appropriated the form, either as a narrative device or as a means of suggesting simplicity. Kipling himself had written some traditional “literary” ballads, such as his romantic evocation of Pathan nobility in the “Ballad of East and West.”

Now he turned the form to describing the experiences of his soldier friends and heroes — from their proud familiarity with their guns (“Screw-Guns”), through the cussedness of camels in the baggage trains (“Oonts”), to the pleasures of service life abroad (“Mandalay”).

From February to July 1890, thirteen Barrack-Room Ballads were published in Scots Observer. In chronological order these were: “Danny Deever,” “Tommy,” “Fuzzy-Wuzzy,” “Oonts,” “Loot,” “Soldier, Soldier,” “The Sons of the Widow” (which Kipling later renamed “The Widow at Windsor”), “Troopin’,” “Gunga Din,” “Mandalay,” “The Young British Soldier,” “Screw-Guns” and “Belts.”

Because Kipling’s best friend in London was the American publisher Wolcott Balestier, these ballads were first published in book form not in London but in New York, where the United States Book Company brought out an edition of Departmental Ditties, Barrack-Room Ballads and Other Verses in December 1890 — an introductory omnibus for the American market, incorporating some of the witty poems Kipling had written in India, as well as his more recent ballads.

Over the next year or so Kipling continued to write Barrack-Room Ballads, but not in the intense manner of those early months of 1890. He was also writing stories, different types of verse, and even a couple of novels (one, The Naulahka, with Balestier). However, in December 1891, Balestier died of typhoid fever in Germany, causing Kipling great grief. To the astonishment of mutual friends, including Henry James, Kipling abruptly married Balestier’s sister Carrie and moved across the Atlantic to her home town of Brattleboro in Vermont.

By then he had composed a further seven soldiers’ songs, which appeared with the original thirteen and many others in Barrack-Room Ballads and Other Verses, published by Methuen in London and Macmillan in New York in March 1892 (the month after his marriage to Carrie). This edition also contained an emotional dedication to Wolcott Balestier.

While writing other works, such as The Jungle Books, in his self-built house in Brattleboro, Kipling continued to produce occasional Barrack-Room Ballads. He sent them to magazines, such as the Pall Mall Gazette in London, and later included them all (by now an additional seventeen) in a special section at the end of his next book of poems, The Seven Seas, published by D. Appleton and Company in a limited copyright edition in New York in September 1896 and by Methuen in London two months later.

This later group of seventeen poems does not have the force of his original Barrack-Room Ballads. To an extent, they reflect the nostalgia of an Englishman living in Vermont for the imperial, military life. One or two have nothing to do with the army at all–“Bill ‘Awkins” is more of a music hall ditty, while “The Mother-Lodge” comes in the category of “fond recollection.” However they do include certain poems that can rank with his earlier soldiers’ songs. “The Ladies” is a sophisticated take on the joys of eclectic sexual experience, “The Sergeant’s Weddin” ‘offers a typically cheeky insight into the behavior of noncommissioned officers, “The Shut-Eye Sentry” is another amusing behind-the-scenes look at regimental life, while “Mary, Pity Women!” brings together the music hall, emotional longing and religion.

Looked at in their entirety, the thirty-seven Barrack-Room Ballads provide a journalistic overview of British army life in the late nineteenth century. Sometimes specific poems, such as “The Men That Fought at Minden” or “Snarleyow,” look back to earlier campaigns, but that is in the nature of ballads — a poetic form that tends to emphasize the continuity of experience, with the same themes continually arising in these tales of barrack-room existence, action in the field and the pain of being away from one’s loved ones.

Kipling ranges over different categories of military service, writing about the engineers (“Sapper”), gunners (“Screw-Guns”) and marines (“Soldier an’ Sailor Too”). He has something to say about most stages of a soldier’s life from recruitment (“The Young British Soldier”) through instruction (“The Men That Fought at Minden”) to going home (“Troopin” ‘) and later reflecting on their military experience (“Mandalay”), and even trying to sign up again (“Back to the Army Again”). He is good on local color, as in “Gentleman-Rankers,” but does not gloss over horrors (“Cholera Camp”) or even politically incorrect practices (“Loot”). While focusing on the camaraderie of soldiers (“Gunga Din”), their antics in the barracks (“The Shut-Eye Sentry”), their drunkenness (“Cells”), their brawling (“Belts”) and their experience in battle (“Snarleyow”), he does not ignore the woman’s role in a soldier’s life — usually as the person left behind (“Mary, Pity Women!”), sometimes a snatched but generally much valued love on the road (“The Ladies”).

While the effect is sympathetic to the army’s involvement in British imperialism, Kipling is not afraid to point out the negative reactions of the rank and file: sometimes they fail to understand what they are fighting for (“The Widow’s Party”) or they resent the condescension and hypocrisy of civilians who seem to love them when they are going off to fight but otherwise scorn or ignore them (“Tommy”).

For the “background accompaniment” to his poetry, Kipling drew on all types of music familiar to the army man, from hymns (“The ‘Eathen”) through the bugle in “The Widow’s Party” and the drum beats in “Danny Deever” or “Route Marchin” ‘ to the ritual funeral march of “Follow Me ‘Ome.”